Memory.

My father was a writer, a Professor of Theater, a story alchemist. His mind was filled with pages that would scatter like leaves in the swell of his internal narrative. My mother had always called him "absent-minded". But I think his mind was actually overfull.

He was diagnosed with Alzheimer's five years ago.

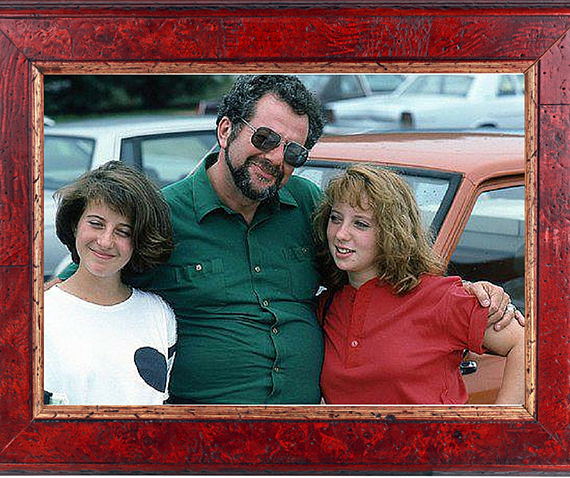

My childhood memories of him contain scenes like when he got lost driving my sister and I back from our annual visit.

It had been two years or so since the divorce, I was about six. As usual, we had spent our time with him in his modest sublet, listening to him bang away at the typewriter while we explored his play-filled bookshelves. Candide. The Glass Menagerie. Waiting for Godot.

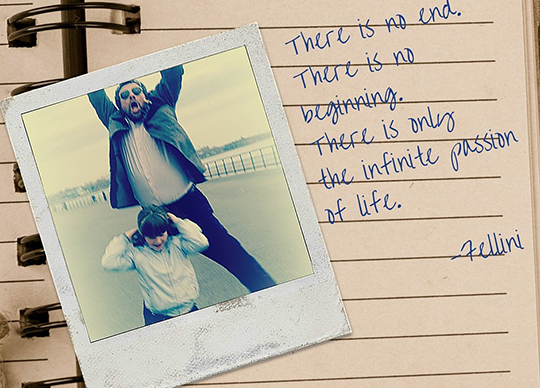

The height of our visits was always those trips to his theater at the college where he taught. Diving into costumes, lingering at the makeup mirror, discovering a playground of props and old sets. He, silently in the background, filming it all with the video camera.

And then the drive home.

My older sister and I had gone from car games to giggling to bickering to pee stops to are we almost there yet to yawns to that meditative stare out of the window.

He must have driven us along this route a handful of times.

It was normally a 2-hour ride home. But his mind had its own clock and his thoughts a different map.

It was dark. Far past the hour that he had promised my mother we would be returned to her. The hour when you can't deny any more that you are lost.

Eventually, my father pulled into a gas station, rolled down the window and asked the attendant where Easton Road was - the main road that would bring us back to my mother's house. Even I could navigate us home from Easton road. But we were not on Easton Road.

There was some pointing this way and that way. Exasperated Oh boy's blown into the ether. Reddening of earlobes.

"That far?! Well how the hell did it get all the way over there?!"

By that point I had given in to my window as a pillow. I knew what was ahead and it was not just a long drive on a fugitive road.

We would finally arrive way past our bedtimes. My mother, greeting us with a relieved embrace, would catalogue his failures through bitten tongue.

My father would or would not respond. He'd give us each one of his trademark, shoulder-crushing hugs, plant one of his sloppy kisses on our cheeks, get into his fading sky-blue Volvo and drive back home the way he had just come.

She'd feed us our re-heated dinner and put us to bed, "...and that ABSENT-MINDED FATHER of yours..." would be whispered in the backstage in our dreams.

Within the false proscenium of their failed marriage, in his defeated surrender to his incapability, in the resentment and overwhelm of a single, struggling, worried mother, there was no space to grieve.

No space to even think about missing him. Or that he might be missing us. Because that was not part of the narrative.

As I write this, I suddenly have a realization about where on the highway of his thoughts he had gotten lost.

It was on the Interstate between His Life and Saying Goodbye to His Children. I would have gotten lost, too.

See that? In writing this part of my father's story, I have just been gifted with a wave of forgiveness and compassion. Perhaps you felt it, too.

Dear time's waste.

We knew that my father was deteriorating. We had just seen him during the winter holidays. His big-hearted, warm, joyous side had bubbled up to the surface.

But he was also tired, confused, falling asleep in his chair, repeating himself all day long. Sonnet 30. Over and over.

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought,

And with old woes new wail my dear time's waste

My father, who could declaim like the best, would lose that last word, over and over.

Regardless, we managed to piecemeal together a 15-minute conversation where I told him about my work as a storytelling mentor and coach. He listened with the pride and love of a father.

Those 15 minutes were no longer about the unsent child support, the new shoes never bought, the college tuition never paid, the wedding that he had not contributed to. The absence.

These 15 minutes were justice for all the conversations we had stopped ourselves from having.

There, at the table, our passion for voice and story made us father and daughter.

I thought that moment would be my goodbye. I thought it would release me from his actual death.

But his death story needed me.

Don't worry. My father's death story is not dangerous. It is beautiful. It is a miracle.

You see, six months later, when I got word that my father had been submitted to the hospital and did not have much longer, I was not back home in Amsterdam. I did not have to take the decision to go or not to go.

I did not have to pick up my phone to hear that it was too late anyway. I did not have to deal with the guilt of not having been there. And I did not have to be left with a realization that our story was never finished.

What happened was story healing.

I had pretty much just landed in the States to spend the summer with my sister when we got the news. We were only a few hours' drive away.

We arrived just in time - he was in his hospital bed, writhing and moaning, waxy and pale, confused, hooked up to every kind of tube and monitor you could think of, in pain, in a loud room he shared with a deaf and amnesiac patient.

"What's your name?! What is the date?! Do you have any family?!"

My father thought the doctors were yelling at him.

He would toss and turn in panic, try to pull himself out of bed, fail. Run his hand over his abdomen in pain. Moan.

My father. Inventor of the belly laugh.

As incapable of full-on fatherhood as he was, and as much as he and I had surrendered to this absence, he was also a man of contagiously infinite passion.

This was not the way he deserved to die.

Dignity.

When he saw me, his eyes lit up with presence. He grabbed my hand. Gave it one of his sloppy kisses.

And then: "Help me, please. Please."

I knew exactly what he meant.

In the Netherlands where I now live, the medical system is a lot more respectful of the need for a death with dignity. Death is about maintaining quality of life to the end, not merely prolonging life itself. In the US, we are often bound by a pious doctrine that takes the dignity away from the dying, puts it into the hands of the insurance companies and protects the doctor from being sued.

My sister and I worked miracles that day to allow my father a death with dignity.

In trying to weave the complicated system of palliative care together, we talked to every doctor and nurse we could - until we found the ones who could help us transition him from suffering in the name of sustaining his failing organs, to taking away the agitation, disorientation, fear, and above all, the pain.

It took all day. Another day of my father writhing and moaning and scared and confused and pleading.

"Please... Please..." His meek pleas were childlike and polite and desperate.

It was finally decided that he would go into palliative care.

After nearly three days in this rapidly declining state, in that compassionless hospital room, he would finally get his own private room, removed from the drama of other patients' stories, tucked away from the bustle of the nurse's station, and overlooking the trees.

The tubes and monitors that had been glued to his chest would be removed. He would be taken off of the heart medication, the antibiotics. He would be given slow doses of Diladed to make him as comfortable as possible.

After nearly 45 hours since he had been brought to the hospital, he finally had peace.

My sister and I filled his last moments by reading to him from a novel he had adapted into a play. He had spent the last decade trying to get staged. We played music from a favorite composer, he had written a play about his wife. We moistened his drying lips. Told him he was going to be ok.

Slowly, as we held the space, my father's hazel eyes began to adopt a different reality.

They were fixated on the corner of the room, a still life, but behind the empty mise-en-scène of the lens was an entire menagerie of characters, scenery and stories.

"He looks like he is directing a play," I said to my sister.

My father had always signed his mails with a quote from Fellini: "All art is autobiographical. The pearl is the oyster's autobiography."

And so I understood.

The palliative nurse had told us that hearing is the last sense to go before death.

My voice was meant to narrate the rest of his autobiography as he left us. My words would give our relationship the narrative it deserved:

"I forgive you for not being the father I know you wanted to be but could not be. I know you have always loved me.

I thank you for enriching this world with your passion.

I thank you for giving me imagination, a sense of adventure, creativity, a writer's voice and a passion for the Story.

You have been, are, and will continue to be deeply, deeply loved.

I love you."

My father's lips seemed to move for a second. He was looking through my eyes. Our story had been his biggest regret. But this new part of the story connected us forever as it released him.

And then, he was gone.

All that was left of his autobiography was my sister, myself, and the soft white pearls of what were once his thick, black curly hair.

Honorific

Alzheimers is a disease that takes the story of your life and throws the pages of memory up in the air. Many blow away. But some land right in your hands.

In Judaism, there is a prayer honorific that is uttered for those we have lost: Zikhrono ilvrakha. May his memory be a blessing.

May his story be a blessing.