Most of us are comfortable with a degree of laxity when it comes to the truth, and even willing to suspend disbelief when it suits our purposes. (I cite the popularity of the Kardashians and FOX News as examples.) When it comes to photography, however, we are less compromising. The essential power of the photograph is its promise of truthfulness. "Something we hear about, but doubt, seems proven when we're shown a photograph of it," wrote Susan Sontag in On Photography. Photos, she said, "furnish evidence" of the world around us. In recent years, digital retouching software like Adobe Photoshop has threatened to undermine the absolute credibility of photographs, but by and large we still look at photos -- news images in the media as well as snapshots posted on Facebook -- with an expectation of truth. And when we learn that the reality they represent differs from what we expect, we can be hugely disappointed. The scholarly debate over Robert Capa's 1936 photo of a Spanish loyalist soldier falling in battle has been long and fierce, precisely because the stakes are so big. Was it staged, as some have claimed? If so, the authority of this iconic war image is severely damaged. Another iconic photo, the French photographer Robert Doisneau's "Le Baiser de l'Hôtel de Ville, 1950" ("The Kiss at the Hôtel de Ville, 1950") was revealed several years ago to have in fact been staged. The embracing Parisian lovers Doisneau snapped were hired models. Posters of the image remain popular, but for many, including me, its stature as an emblem of impulsive passion is diminished.

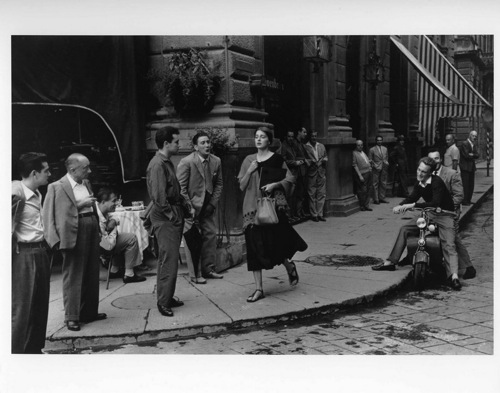

"American Girl in Italy, 1951" Copyright 1952, 1980 Ruth Orkin

I don't feel the same way about another photograph whose authenticity has been the subject of debate. Photographer Ruth Orkin's "American Girl in Italy," a richly textured black-and-white shot of an exquisitely tall young woman rushing down an Italian street, apparently distressed by the leering attention of a group of men, has been a popular classic of 20th century photography since it was mass produced as a poster in the 1970s. What makes this image so beguiling is its combination of visual beauty, cultural identity, and sexual politics, all framed in a singular moment that seems to reveal something quintessentially true about human nature. As I learned recently when I wrote about the image for the October issue of Smithsonian magazine, the truth behind the image is more complicated than I had imagined.

Orkin, who died in 1985 at age 63, took what would become her best-known photo a little more than 50 years ago. An intrepid woman (at age 17 she bicycled from Los Angeles to New York), Orkin had gone to Italy on her own after completing a Life magazine photo assignment in Israel. There, at Florence's Hotel Berchielli, she met 23-year-old Ninalee "Jinx" Allen, a recent graduate of Sarah Lawrence College who was happily spending a summer in Europe. On August 21, 1951, the likeminded pair set out to create a picture story about a young woman off on a solo European adventure. Orkin thought she might be able to sell the story for a few dollars to International Herald Tribune newspaper.

The circumstances surrounding the taking of the picture have never been disputed: Orkin and her model wandered along the Arno River, then turned into the nearby Piazza della Repubblica. When Orkin saw the reaction of the men loitering there, she bounded into the intersection and clicked. She then turned to one of the men. Would he, she asked, tell his friends to avoid looking at her camera while she took another picture? Jinx retraced her steps, and Orkin clicked again. It was the second shot that was perfect.

But was it? There are those who say no, because it was a recreation and not the unadulterated actuality they expect from photography. Strictly speaking, that's true, but I don't find the photo misleading--the truth we perceive in it seems real enough. In this case, it may be wiser to think of the photograph not only as evidence but also as literature. The camera's mechanical eye takes in exactly what it sees, but there is always someone behind the camera who is telling a story. At any rate, the American girl in the picture stands by its truthfulness. "The men were not arranged or told how to look -- that is how they were in August 1951," says Ninalee Allen, now Ninalee Craig, age 83 and living in Toronto.

It is also wise to remember that when photos do mislead, the fault often lies with the observer. Craig told me that, contrary to what many have said, she was not at all distressed that day in the Piazza. That expression on her face? She was imagining herself as the noble Beatrice of Dante's Divine Comedy.

You can read more of my interview with Ninalee Craig on my blog, The Big Picture.