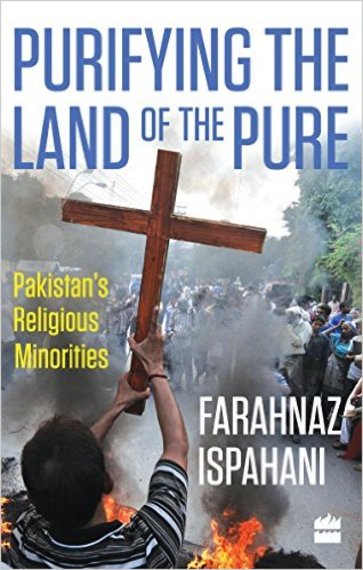

Photo Source: Amazon.com

Since its creation in 1947, Pakistan's political leaders and scholars have constantly debated the degree to which their country should refer to Islam as the source of national identity. There have been various justifications why Pakistan had to be carved out of the United India. The religious lobby argues that Pakistan was supposed to be a country for the Muslims where they could live their lives according to the "true teachings of Islam", while the tiny faction of the liberals insists that the country was meant to be secular. Founding fathers espousing these divergent points of view were soon caught fighting about the role of Islam in the fledgling Muslim state.

Islam became such an emotive topic in Pakistani politics that political and military leaders used it alike to manipulate public opinion and make electoral gains. Religious minorities ended up as the worst victims of this flagrant use of religion for political gains. Ultimately, this led to disastrous consequences for the Muslim-majority nation's religious minorities who up till now regularly face discrimination, death and destruction because of their faith.

In her fresh book, Purifying the Land of the Pure: Pakistan's Religious Minorities, Farahnaz Ispahani, a former member of the Pakistani parliament and a liberal intellectual, explains the deplorable conditions of minorities in her country. Ispahani, while providing a historical background of how Pakistan fell in the hands of religious extremists, argues that Pakistan's founding father, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, a western-educated lawyer, had envisioned a modern secular country in which everyone would enjoy religious freedom. The religious lobby, she regrets, hijacked Jinnah's Pakistan.

Jinnah, Liaquat and Suhrawardy are three important characters of Pakistan's history who are mentioned at the beginning of the book. Statements, decisions and actions of these three leaders would go on to have a profound impact on the future of Pakistan. Jinnah and Suhrawardy, a Bengali politician whose quote is featured at the start of the book, are seemingly the heroes of Ispahani's book because of their secular thoughts.

Soon after Pakistan's independence, Jinnah told his nation:

"You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place or worship in this State of Pakistan...you may belong to any religion or caste or creed - that has nothing to do with the business of the State."

Liaquat, the first prime minister, is the bad guy in the book. He leads the faction of the Muslim League leaders who see Jinnah's speech cited above as the 'abandonment of the two-nation [Hindu-Muslim] theory'. Liaquat and his supporters resisted Jinnah's plans to secularize Pakistan. Backed by the bureaucracy, Ispahani notes, Liaquat even tried to suppress Jinnah's speech that promised religious freedom to everyone. In 1949, one year after Jinnah's death in 1948, Liaquat introduced the Objective Resolution, a major step toward providing Islam constitutional space. Ispahani says Liaquat "led the way in creating a national narrative for Pakistan that perpetuated the sense of Islamic victimhood."

After the Objective Resolution, which paved the way for Islamic provisions in the constitution, successive rulers passed numerous laws that provided legal space for the influence of Islam on the constitution. Because of these laws, religious minorities face blatant discrimination, violence and suppression.

Pakistan's minorities can be classified in three categories.

First, there are the followers of world's major religions such as the Christians and the Hindus. Many of them fled the country soon after the creation of Pakistan. Those who stayed in Pakistan are constitutionally barred from becoming the head of the government or the state. Sunni extremists routinely attack their places of worship, forcibly convert them into Islam and, in several cases, kidnap their women and compel them to marry Muslim men. The clergy and devout Muslims regularly use the notorious blasphemy laws as a blackmailing tool to provoke Muslim mobs to attack these non-Muslims or burn their homes based on wild accusations, such as the burning of the Quran or disrespecting Prophet Muhammad.

Second, the Ahmadiyya community has faced horrible crimes since Pakistan's creation. Although the Ahmadis, as the members of the community are known, identify themselves as Muslims, Pakistan, which is home to the world's largest number of Ahmadiyya (approximately four million), does not recognize them as Muslims. In 1974 Pakistan became the world's first (and until today the only) country that lists the Ahmadiyya as 'non-Muslims'. Ispahani's book lists several shocking incidents when the Ahmadis were severely reprimanded for several minor 'crimes' such as using the Muslim greeting. For instance, Ispahani reports that one Ahmadi shopkeeper was convicted and handed a six-month prison sentence because he said the greeting to a passer-by.

Third, the Shias cannot technically be described as a 'religious minority' since they do not belong to another religion outside Islam. However, in the Sunni-majority Pakistan, the Shias, who make roughly 20% of the population, are subjected to severe sectarian violence. According to Ispahani, "once the Ahmadis were officially declared non-Muslim in 1974, a new campaign started with the intent to subject the Shias to similar proscriptions." Every year, hundreds of Shias are killed in suicide bombings and targeted killings carried out by Sunni extremist groups. The Sunni-Shia battle in Pakistan is frequently attributed to a proxy war between Saudi-Arabia and Iran that is being fought on the Pakistani soil. That could be one factor in escalating sectarian violence but we cannot snub the local factors that contribute to this violence.

Farahnaz Isphani (Photo Source: https://farahnazispahani.wordpress.com)

As religious extremism deepens in Pakistan and the three minority groups mentioned above see no end to these horrific crimes, Pakistan is increasingly witnessing the emergence of a fourth minority group. This is the group of Sunni Muslims who are also targeted by extremist groups for advocating moderation and tolerance. Reformist Muslim voices that stand up against these extremists are also violently silenced. Former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, who was killed presumably for her liberal views, Governor Salmaan Taseer of the Punjab province, whose security guard gunned him down for criticizing the discriminatory blasphemy laws and Malala Yousafzai, the young campaigner for girls education who was almost killed by the Taliban all represent Pakistan's constantly endangered Muslim minority.

Declaring the Ahmadis as non-Muslims in 1974 was indeed a dark episode in Pakistan's history when the country's political leadership, led by Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), succumbed to the pressure of the religious groups. Had the government decided to stand by the endangered Ahmadiyya community and discouraged the religious parties' unreasonable demand, it could have redirected Pakistan's path toward tolerance and communal harmony.

The first question anybody familiar with Pakistan's history would ask while picking up the book Purifying the Land of the Pure would probably sound like this: Does the author criticize Mr. Bhutto for the laws against the Ahmadis? [Ms. Ispahani belongs to the PPP]. Unfortunately, the answer is no. Ispahani argues that Bhutto had acted under pressure from the religious groups and he "expected the measure to steal the mullahs' thunder; instead, it only encouraged them to make further demands over the next few years." That isn't a convincing pretext to wash Mr. Bhutto's sins.

Purifying the Land of the Pure extensively documents the violence perpetrated against Pakistan's religious minorities. It is deeply concerning, for which the writer surely cannot be faulted, that the book does not list any plans and strategies currently applied by the Pakistani government to improve the conditions for its religious and sectarian minorities. Islamabad has recently flaunted over the successful military operations against the Taliban but that means nothing in terms of ending discrimination against minorities.

Pakistan's civil and military leadership are equally responsible for ignoring the past and present extremist attacks on minorities. Whether the Pakistanis wish to keep their country an Islamic republic or transform it into a secular state, they must protect minority rights. Under no circumstances should such violence be tolerated.