Nothing revealed Stanley Kubrick's singular intelligence -- nor his endearing humor and humanity -- more than budgetary decisions. He wore his producer's hat as ingeniously as his director's one, confounding expectations.

Before he arrived in New York for the opening of 2001, stories of his obsessive genius preceded him. He had a pilot's license, but wouldn't fly after monitoring the control towers at various airports, finding their safety inadequate. He knew the best dental procedures and rumors spread that he had an open telephone to the dentist's office when a family member underwent treatment.

My first encounter with his financial concerns came shortly after Stanley, his wife, Christiane, and their daughters, Anya, Vivian and Katherina moved into a large suite at the Pierre Hotel upon their arrival in New York. It was his first visit to the United States in many years, after moving to England following Spartacus. His stay would be charged to the film, of which he had a large percentage.

When he saw that a glass of fresh orange juice cost $1.50 from room service -- he was shocked. He asked for menus from twenty first-class hotels to compare orange juice prices. The publicity staff scurried to comply.

Seeing there was little price difference among first class Manhattan hotels, he moved the family to a rented estate in Great Neck for their two-month stay. (The house had a landing with a light facing Long Island Sound; such was the interest in anything Kubrick that rumors quickly spread it was the actual setting of Jay Gatsby's mansion in The Great Gatsby.)

I was his point man for 2001 immediately following its problematic opening. Devoting much of the following year to redirecting the marketing approach, it was evident that audiences only wanted to see 2001 in its original format, in Cinerama, with full technical bells and whistles. I was in constant touch with Stanley, who fully supported its 70 mm relaunch at The Ziegfeld in March 1970.

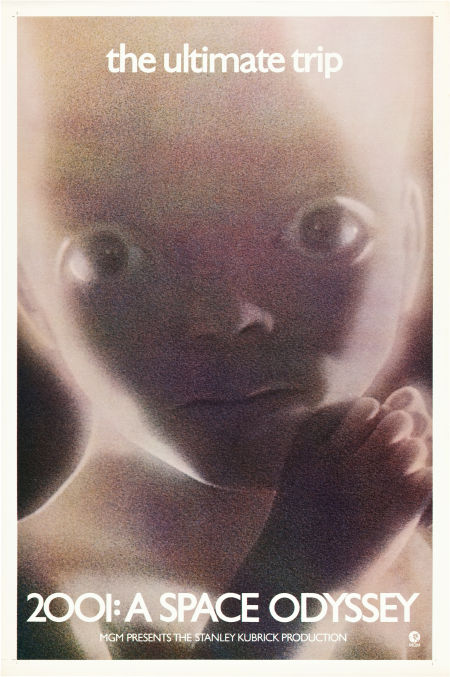

Shortly before the opening, MGM finally decided to create a new marketing campaign. My boss, Mort Segal, gave me the news which I had long awaited, convinced the initial "hardware campaign" of space vehicles and helmeted astronauts dehumanized the film and limited the audience. Mort asked, 'What should it be?"

Instinctively I saw the StarChild, the mysterious, inviting embryo with eyes wide open that stimulated much of the film's controversy. Stanley had placed an embargo on using any stills or footage of the film's final sequence, where the StarChild evolved, as well as the Dawn of Man sequence, which opened the film. He felt those images outside of the context of the full film would confuse the audience.

Now, two years after the film's opening, when the ending had been intensely dissected, centering the campaign on the embargoed StarChild would be inherently striking and illuminate 2001's human dimensions.

However, I didn't want to chance his disapproval until the artwork was completed. I'd been riding the campaign turns like riding waves and knew it would work. Three or four frames were taken from the film and soon a comp came back with the StarChild filling the entire poster -- with THE ULTIMATE TRIP as its slogan.

Cornel Wilde, who was leaving for England to begin his environmental thriller, No Blade of Grass, was given a proof for Stanley.

Stanley didn't like it.

I reasoned why it would work: the campaign was aimed at 2001's young, core audience, who went to repeated viewings; it was intriguing in its own right to a wider audience; MGM was now fully behind the approach.

It was a rough call: Stanley could have blocked the campaign and it could have ruined our relationship. Finally, he agreed. "OK. Go with it. "

Then the caveat: "But my credit has to be above title. That's legal."

The ad agency had placed "MGM presents The Stanley Kubrick Production" below 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY.

The printing plates were already made when I called the agency. The credit could be repositioned for $5,000.00. I called England.

"Stanley, we can make the change but it will cost five thousand dollars." ($35,000 today.)

A long pause.

"Oh forget it."

He didn't want to add any more expense to the picture's cost. His ego needed no credit validation.

Of course, my favorite "budget" encounter came three weeks before the premiere of A Clockwork Orange. During production of Clockwork, Kubrick sent a letter saying I was the only one who knew how to handle a Kubrick film and would I leave MGM and work directly for him in England.

It was flattering and unexpected. But it didn't take long to make the decision. It was an opportunity for a new experience; I was 28 and confident in my abilities.

Everything was controlled and completed from a suburb outside of London. Today, teams of studio executives have to sign off on everything and then lawyers go through it again. With A Clockwork Orange, everything emanated from Abbots Mead via Stanley's control.

We strategized twice a day -- at lunch and at the end of working hours. Memos were to be concise, no longer than two succinct paragraphs, following the procedure developed by the Navy SEALs.

To make sure everything was properly covered, he quickly pointed out the virtues of the Daytimer, the diary designed to organize one's work schedule and appointments. He had investigated similar products and decided the Daytimer was the most efficient.

Being young and certain my memory never faltered, I felt I could remember everything we discussed. Stanley, however, was never without his Daytimer, and after several weeks of insisting on how much easier it would be to work together if I used one, I was driven to London to select the personal components of my own, fine leather, two-page a day system.

He was right. Each day we'd take out our dueling Daytimers and go though our checklist. (Years later, working with Robert Altman, I had a leather pouch made for it which Bob called "the holster.")

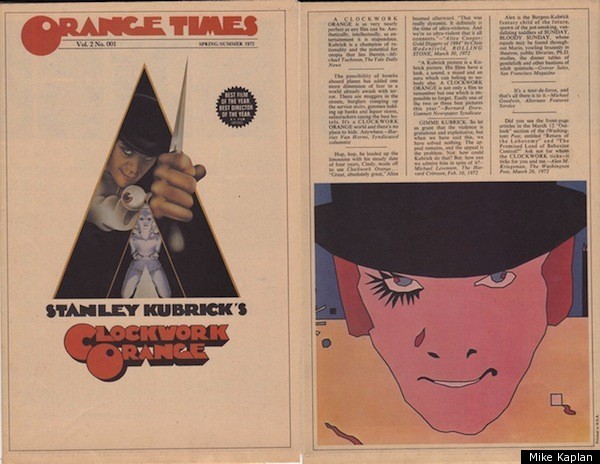

Three weeks before opening, it was high-alert time. Consumed with: finalizing logistics, coordinating Stanley's quote approvals, confirming Pablo Ferro's inventive trailer was on screen, checking the labs' black and white still conversions, designating screening seats of the high powered critics, proposing advertising buys, organizing Stanley's final configurations of Philip Castle's key art, and beginning Orange Times, the comprehensive editorial handout that would become both the production notes and the solution to the advertising ban in markets where X-rated films had limited media access.

Stanley, meanwhile, was overseeing the final color corrections at the lab. Weeks earlier, the negative had been accidentally scratched at Humphries, where all the processing had been effectively handled for over a year. The technicians were devastated as Stanley removed the negative to Rank via a convoy of vehicles, followed by Humphries' managing director on foot, trying to rescue the transfer. There was no sanctioning an error of this magnitude.

Stanley was also feeling pressure with the final dub at Elstree Studios.

And then came the human element to level the stress.

We're in his office for our mid-day meeting with my open Daytimer, waiting for his to appear. Nothing emerges.

"I have a present for you," came the surprise.

I looked at him, flummoxed

"A present?"

Stanley turned around to a table in back of his desk and hands me a flat, unwrapped box.

I opened it. It was another, larger Daytimer.

"It's a Desk Daytimer " he explained. "You use it to write everything down at your desk."

I looked at him, incredulous, then put "the present" down.

"Thanks, Stanley, but no thanks. I can't use it."

"Why not?"

In the past, I would have taken it and moved on, but years of being exposed to his acute Socratic logic about all things had permeated by brain.

"If I have to write things down at the desk and also write them down in the portable Daytimer, it's repeating the same function and I don't have the time."

Stanley looked at me with the innocent half-smile he would have when trying something out -- the cat-spilling-the-milk look.

"Yeah, I know. I figured that out too."

Checkmate.

I didn't skip a beat talking through the day's demands but walking across the Chantry lawn to my office, I couldn't help laughing.

Stanley had bought the desk Daytimer as an adjunct to his current organizing scheme, determined it was useless, and tried to pawn it off on me. He figured if I took it and found a way to use it, the cost would be justified.

Kubrick, the creative genius, whom Anthony Burgess confirmed had found "the cinematic equivalents" to his novel immediately after seeing Clockwork; whom Arthur C. Clarke stated knew more about the potential of space after making 2001 than any rocket scientist; Kubrick, the master satirist, had found time to plan the offer of my "present" in the heat of bringing A Clockwork Orange into the world.

His plan didn't justify the cost of the Daytimer; it justified the reason we were there.

For besides the high of being a part of the cinema envelope he was pushing, one never knew what Kubrick surprise would rear itself at the most unexpected time, make you shake your head in wonder -- and smile.

This is the fourth in a series of reminiscences about Stanley Kubrick written by Mike Kaplan, a veteran film executive who was Kubrick's marketing man for his film 'A Clockwork Orange,' having also worked extensively on the release of 'Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey.' Previous installments can be found here, here and here. 'A Clockwork Orange' opened nationally 40 years ago this month.