I was 14 years old when Hurricane Katrina ravaged my city, flooded my house and forever changed my world.

Growing up in New Orleans, hurricane evacuations weren't uncommon. Every few years, we'd find ourselves at the center of some distant storm's projected path. We'd all pay extra close attention to the weather reports, and as a precaution, the mayor might issue a voluntary evacuation order. School was canceled, windows were boarded up and small bags were packed.

My family would always set off for Houston where, after spending 15 hours in bumper-to-bumper evacuation traffic, we'd stay for a few days until the hurricane made landfall, inevitably having weakened or changed its course. Damage in NOLA would range from minimal to nonexistent, and we would go home and get back to life as it had been before hurricane season. At least, that's how I always remembered it.

Katrina wasn't like that.

Instead of tracking the storm's progress throughout the week, I wasn't even aware of it until a few days before it struck. On the night of Friday, August 26, I was at my brother's high school football game, blissfully oblivious to the quiet murmurs of a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico. By Sunday, August 28, at 3 a.m., my family and I were in our car en route to Houston. Mayor Ray Nagin had issued the first mandatory evacuation in the history of the city, and those who didn't have the means to leave were piling into the Superdome.

The following morning, Hurricane Katrina made landfall in New Orleans. I remember sitting in a Houston hotel room, glued to the live news coverage of the storm. The streets of downtown New Orleans were flooded, but it could've been much worse. I remember my parents saying it looked like most major infrastructure had held, even floating the possibility that we'd get back to school in a matter of weeks.

Then the news broke about the levee breaches. Water gushed into the city, bringing with it a wave of destruction and uncertainty. That's when it really hit me that this was not going to be like the hurricane evacuations I'd experienced in the past.

I had so many questions for my parents, my siblings and my friends. What was going to happen next? Did our house flood? Did everyone's house flood? How long would it be before we knew? I just wanted answers, but nobody had any.

New Orleans underwater, five days after Hurricane Katrina hit.

When you're a teenager and life feels like a big confusing mess, there are certain things you can usually count on -- like, where your home is. But after Katrina, I didn't even have that anymore. All I knew was that we wouldn't be going back to New Orleans. At least not for awhile.

My parents regrouped, and we drove up to Kentucky, where we could stay with family for a couple of weeks while we figured things out. When we got out of the car at my aunt's house, I immediately started sobbing. My relatives greeted me with warm hugs, and my mom quickly snuck inside the house, because she didn't want me to see that she was crying too. That week remains a blur of tears and hugs and gifts from generous neighbors and business owners.

We tried to figure out the state our house was in, but secondhand information from neighbors and aerial imagery from Google Earth could only tell us so much. My parents decided that they would have to go see the damage for themselves.

After making the 10-hour drive to New Orleans and somehow talking their way into the closed-off city, my parents parked on dry land, put on fishing waders and made their way down our flooded street -- a street that sloped downward, with our family home the bottom. My mom and dad waded through the water, which wasn't really water so much as a thick sludge filled with sewage, trash, dead animals and even people.

When the substance reached chest height, my mom didn't want to go on any further. She waded over to a neighbor's elevated porch while my dad continued onward. Eventually a man in a small boat spotted my mom and offered to give her a ride. She asked if he could take her to our house down the block, and he gruffly replied that he could take her there but would not be waiting around to bring her back. She accepted the ride.

When she got in the boat, she saw he had a gun. Rumor had it that local police chiefs were issuing "shoot-to-kill" orders when it came to looters. My mom, who wouldn't willingly go within 50 feet of a loaded firearm if you offered her a million dollars, was terrified. At the end of the short ride, she got out of the boat and made her way inside our flooded house.

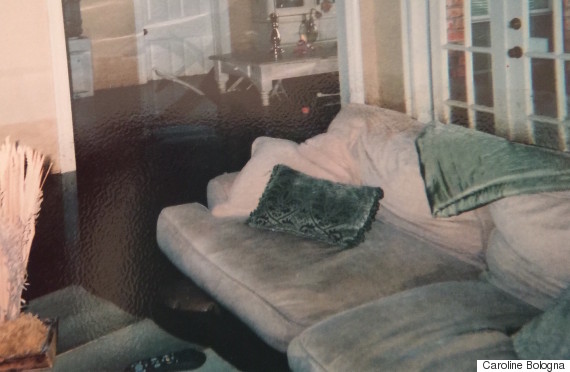

It was all ruined: the floors, the walls, the furniture, the appliances. The photos my dad took of the damage during that first visit and a few subsequent trips after the water subsided showed that the wood was buckled, and mold and mildew were forming a strange pattern on the walls. It almost looked like it was just some oddly funky wallpaper my parents never would have picked out.

The more personal items were completely destroyed. The family photos we displayed around the living room, the baseball cards my dad had been collecting for over 50 years, the old toys we stored in the garage to pass down to future generations, the vinyl records my mom had kept since her teen years, and the upright piano she had purchased as a college music major in the '70s -- the same piano where I had learned to play everything from "Chopsticks" to Chopin.

Standing water in my family home during my parents' first visit.

The ruined wood and strange pattern of mold and mildew on the walls.

The upright piano my mom had kept since her days as a music student in the '70s.

Weeks after the floodwaters subsided.

But my family and I were some of the lucky ones. We had a two-story house, and our bedrooms were upstairs, safe and sound. We didn't live right on the Gulf Coast where entire houses were ripped out of the ground. And most importantly, we had our lives.

At least 1,800 people died in the storm. We knew people whose grandparents had drowned in their homes, those who had traumatic experiences breaking through their attic ceilings with an axe and then waiting for help on the roof, and those who had evacuated and then returned with boats to rescue stranded survivors. There were also those who couldn't survive the aftermath. My community post-Katrina was filled with stories of depression, divorce and suicide.

My family was back in NOLA by Christmas, after spending four months in an area just outside Baton Rouge. Our house was gutted and rebuilt and livable by the following June. Throughout it all, my parents did everything in their power to make me feel safe and loved, my teachers dedicated themselves to maintaining a sense of normalcy, and my friends embraced the novelty of our wacky post-Katrina lives -- filled with FEMA trailer sleepovers, protests for better levee protection and weekends spent gutting houses.

My school offered community service opportunities to go to severely damaged neighborhoods and help gut flooded houses.

My classmates and I at a rally for better levee protection during one of George W. Bush's post-Katrina visits.

On the occasion of the 10-year anniversary, people from areas affected by the storm feel up to our ears in thinkpieces written by people who have no ties to the city of New Orleans. There's an overwhelming pressure to look back and figure out what we've "learned." And there's a lot of talk about "resilience." The resilience of the city, its adaptation to climate change, its dedicated citizens.

To me it's never been about resilience. New Orleanians are just special, spirited people -- you have to be to live in such a fiercely unique city.

But, looking back, as one is likely to do after a decade, I have "learned" some things. My personal lessons from the trauma of Katrina range from "keep your most sentimental items in one place so that you can easily gather them in the event of an evacuation" to "don't eat your feelings" (lest you gain 15 pounds of "Katrina weight" like I did). I learned how to gut a house with a sledgehammer. Eventually, I learned how to look at the story of Katrina through other lenses, to contextualize my experience of the storm and recognize how it was different from what many others lived. And I've learned to "count my blessings," as Pollyanna-ish as that sounds.

Ultimately, being a Katrina kid, I've learned about the limitless love that every member of my family possesses. I've learned how devoted they are to making sure I feel safe, no matter how uncertain or bleak the circumstances. I've learned that nothing in life is certain -- not even where you live. And most importantly, I've learned that home lies in people, not property.

Also on HuffPost: