Recently, the Berggruen Institute’s Dawn Nakagawa interviewed John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge of The Economist about their new book, “The Fourth Revolution: The Global Race to Reinvent the State.” Micklethwait is The Economist’s editor-in-chief. Wooldridge is the magazine’s management editor and writes the Schumpeter column.

The WorldPost: The title of your book is “The Fourth Revolution: The Global Race to Reinvent the State.” What were the three earlier revolutions, and why do you see a fourth on the horizon?

John Micklethwait: Briefly, these three revolutions were the birth of the modern nation state, then the liberal state and then the welfare state.

Now that the welfare state has grown too large to afford, the fourth revolution involves forging a limited state that reduces costs, for example by applying new technology to the delivery of education and health care. This more limited state needs to engage citizens more deeply by devolving powers as much as possible toward localities. At the same time, certain decisions concerning the long-term and common good, such as monetary policy or getting entitlement spending under control, should be delegated to non-partisan technocrats or specially appointed commissions not beholden to raw public opinion, special interests or political patronage.

But let me step back to give some historical context.

From the perspective of 1600, China should have defined the future of the world. Europe at that time was a squalid backwater.

Only three cities in Europe, London, Paris and Nice, had populations of more than 300,000 people. That was the population of The Forbidden City alone -- many of them Mandarin intellectuals selected by examinations from the whole country to administer the empire. But then the balance of power shifted dramatically in favor of Europe because of the three successive revolutions I have noted.

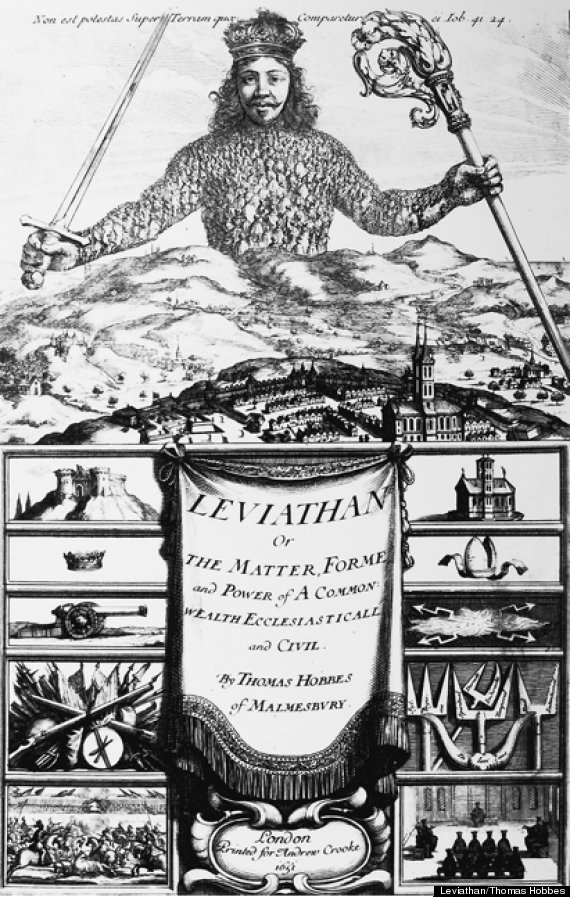

The first revolution was the creation of the nation-state, which offered security to people within it. The feudal aristocracy was tamed and religious factionalism was neutralized -- “the Prince determines the religion.” While power was centralized internally, competition between states propelled them outward, trading with the rest of the world and, in most cases, establishing empires: tiny Portugal conquered Brazil and Britain ruled three-quarters of the world. China, meanwhile, turned inward as the emperor ordered all subjects living on the prosperous southern coast to move 17 miles inland so they wouldn’t be contaminated by trade and foreigners.

The second revolution was the liberal revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries, which made governments accountable, efficient and respectful of individual freedoms. In the book, we focus on 19th century England because it was then the great power in the world and the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, but the earlier American and French revolutions were also a part of this shift.

Adrian Wooldridge: There are lessons for today from England’s liberal revolution. At that time, England actually reduced the size of government; public taxation fell from £80 million a year in 1815 to £60 million a year in 1846 –- even as the population was growing by 50 percent and new schools, police and sewage systems were put in place.

The relevant lesson for today is that this was done by replacing government through patronage and sinecure with a meritocratic civil service selected on the basis of examinations. It was consciously modeled on the Chinese system.

In short, they got rid of corruption, protected the rights of individuals and made the state more efficient and accountable.

As we are all familiar through the literature of Charles Dickens, this utilitarian calculus fell hard on the poorest. Reformists argued that the state should show compassion by addressing social issues. At the time, they looked to the bigger, more activist German state, which invented the pension system, and asked “why can’t we go that direction?”

That laid the foundations for the third revolution which began at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century -- the activist welfare state.

John Micklethwait: In the U.S., the welfare state didn't take off until FDR in the 1930s in the wake of the Great Depression. That was followed later on by Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and the War on Poverty. The state got bigger and bigger, even as America was fighting the Vietnam War and building up its military might vis-a-vis the Soviet Union. Debts were piling up; New York City almost went bankrupt.

REAGAN AND THATCHER: A HALF REVOLUTION

Adrian Wooldridge: Then came what we call a “half revolution” –- the Reagan and Thatcher movements against big government. In Britain, this meant getting the state out of running companies from telecoms to railroads. Thatcher sought to de-nationalize Britain. Even with her privatizations and despite vigorous rhetoric, in the end she only reduced the welfare component of state spending from 22.9 percent to 22.2 percent.

In the U.S., Bill Clinton was quite good at controlling state spending and reducing the deficit, but George W. Bush certainly wasn’t. By extending Medicare benefits to prescription drugs and fighting the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, he expanded the American state more than any president since LBJ. In Britain, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown were initially quite good at controlling public expenditure, but then very rapidly they lost control of government, and the state began to expand again. And then of course, the financial crisis hit, and perhaps justifiably, we saw a big surge in spending.

John Micklethwait: The overall observation here is that people continually want more. And in democracies, they elect people who promise to give them more whether they can afford it or not. Sometimes that comes from the right, sometimes from the left. Sometimes it is better health care and schools; at other times it is prisons and fighter jets.

This, then brings us to the fourth revolution, a kind of return in modern times to the liberal conception of the state that no longer believes in big government, but protects the individual while competently and efficiently delivering limited public goods.

We think the state is incredibly important: we don’t agree with libertarians who argue that he governs best who governs least. If it's incredibly important, you have to actually make it work better. And one of the ways to make it work better is to make it do fewer things. The state simply cannot afford to do everything and be a person’s perennial accomplice in life.

Otherwise, the state is going to run out of money. Since 2007, the West –- America and Europe -– has borrowed 16 trillion dollars! That simply can’t go on forever.

Half that amount is on Central Bank balance sheets, but the rest is for outright spending.

The demographic reality alone -- people getting older –- makes it clear that a bust is coming. Fewer people of working age are having to support a growing population of retirees, particularly in Europe but also in the United States. That is one reason for the next revolution. The other is on the more optimistic side. New technologies can make everything from medical care to education cheaper and more efficiently delivered. In a sense, we are at a parallel stage to the early moments of the Industrial Revolution when it comes to costs. Just as the Industrial Revolution radically reduced the cost of manufacturing and transport, so the Information Revolution is radically reducing the cost of information-intensive services, which lie at the heart of the state.

The other big reason for optimism is competition -- going right back to the first revolution of Western nation state in competition with each other. Today, the Western nation-state is in competition with another way of governing and providing services -- the Asian model of Singapore and China.

Adrian Wooldridge: For the last four or five hundred years, the West has had the world to itself. It's had a monopoly of ideas, a monopoly of innovations and has ruled the world as a result of that. For the first time ever, we're seeing innovations in governance and ideas coming from all around the world.

For example, you can look at the Brazilian system of conditional cash transfers, where welfare payments depend on parents sending their children to school and getting them vaccinated. That's a very good idea. To take another example, Devi Shetty, an Indian surgeon, has radically reduced the cost of heart operations by applying economies of scale and scope to running his hospital. Of course, the biggest alternative to the West is China governance system -- the top-down, Mandarin-style government which combines regular rotation of leaders and transfer of with more long-term planning.

The future should, and probably will, lie with democracies and liberal capitalist countries, but only if those liberal capitalist countries get a bit fitter and shed our flabby and self-indulgent ways.

We need to shape up. That means shrinking the state a bit, making it smaller and more focused, and thus much better at providing services. More focus will actually make the state more legitimate in the eyes of voters, because it will stop promising more than it delivers.

The WorldPost: Part of your answer to the various failures of democracy is both to move power up by putting it in the hands of technocrats and, at the same time, empower the public more directly through devolving toward the grassroots.

How do you envision this “technocracy plus direct democracy” working in practice?

John Micklethwait: Democracy requires a careful balance of responding to the will of the people and taking a long-term perspective for the good of the society and future generations. Direct democracy has a tendency to be too short term focused, volatile and reactionary, as we have seen from the results of the initiative process in California. On the other hand, if you remove decision-making away from the people it can become disconnected and breed discontent.

The way to do this is to place the responsibility for some things, such as monetary policy, in the hands of entrusted institutions such as central banks. This system has reduced inflation’s impact on the economy precipitously everywhere that it has been implemented.

We also believe that specially appointed non-partisan commissions should be responsible for reviewing and setting entitlement policy on a periodic basis. If defining entitlements is left to the will of the voting public, it enables the current generations to rob future generations, as we are seeing across the Western world today.

However, there cannot be too many things decided by technocrats, as we see in the European Union today at the commission level, or the system loses legitimacy. Powers must be devolved so that local government can be centers of decision-making. This is something the U.S. has always been quite good at.

The trick is to harness the twin forces of globalism and localism, rather than trying to ignore or resist them. With the right balance of these two approaches, the same forces that threaten established democracies from above, through globalization, and below, through the rise of micro-powers, can reinforce rather than undermine democracy.

The WorldPost: In a twist on your approach, former Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti has said that the EU Commission in Brussels is what you might call “the technocracy” that looks to the long term and European common good and only takes on such competencies; while the nation-state democracies deal with more short term, national issues.

John Micklethwait: For the EU, we argue for the devolution of power to the member states and within the states to localities. Empowered and accountable local government will give the system legitimacy. More power should be pushed down to the local level, leaving only a few important elements to the EU.

The WorldPost: To quote Monti again, tough structural reforms take time to mature and are unpopular, but the voters want results now. So the reformers are always booted out in the next election. Democracy misprices the long term.

This happened to Gerhard Schroeder in Germany –- he was booted from office because of the unpopular reforms that have now made Germany the powerhouse of Europe.

Monti’s experience at the height of the euro crisis taught him that only a “grand coalition” is capable of making long-term reforms that entail short term costs. Then all parties are equally insulated from backlash. Otherwise, the partisans will paralyze each other with the next elections in mind.

Do you agree with this conclusion? How does this fit with your approach?

Adrian Wooldridge: Monti is certainly right that democracies can misprice the long-term. He is also right that, in his own case, he got the blame for making necessary reforms. Italy is a better place for his reforms. But we have two problems with his approach.

The first is that, if you load too many long-term decisions onto EU institutions, you risk a nationalist backlash of the sort that we saw in May’s European elections, which saw France’s National Front winning a quarter of the vote. People are much happier if national institutions, such as central banks or non-partisan commissions made up of former national politicians, take tough decisions.

The second is that, contra Monti, national politicians can sometimes push through tough structural reforms. The Swedes, and to a lesser extent other Nordic countries, did this in the early 1990s, when they reached the limit of debt-fueled big government. David Cameron has also done a good job of cutting the size of government after the Labour Party’s binge spending. The British people would certainly not have taken the same medicine from Brussels. In fact, Cameron’s insistence on bringing down the debt and trimming public services, has wrong-footed the Labour Party, which, after briefly flirting with offering the voters more of everything, has fallen in line with his emphasis on austerity.

Contracting out all difficult decisions to remote technocrats in a foreign capital is neither necessary nor, given the current distemper in Europe, particularly wise.