We've come to use the word "sexy" to describe politics. Sex sells, and in order to compete with everything else screaming for attention, politics must also be sold.

This isn't entirely cynical: Politics should be sold because public opinion matters. Politicians, governments, laws and treaties all benefit from favorable public opinion and that means connecting with citizens through the traditional and new media, as well as grassroots mobilization. Elections are the biggest public opinion game in politics because they end in a definitive, measurable vote.

Some elections sexier than others. The entire 2008 U.S. campaign -- from primaries to the general election -- left us breathless. On the other hand, Bush vs. Gore in 2000, and Spain's Rajoy vs. Rubalcaba in 2011 could have been marketed as insomnia remedies. However, presidential campaigns, where two candidates battle it out to become the leader of the country (or in the case of the U.S., the leader of the free world) are generally a lot more interesting than congressional or parliamentary elections with no presidency at stake. Voter turnout figures back this up.

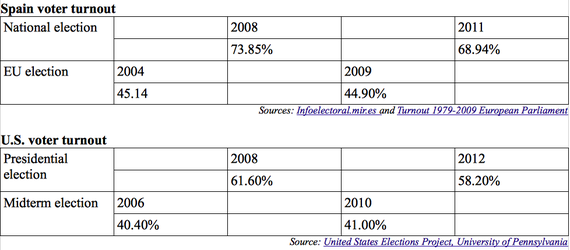

Take the U.S. mid-term election this coming November, where the House of Representatives and one third of the Senate will be chosen. Sure, the stakes are high, but hundreds of messages, slogans and personal narratives are much more difficult to wrap one's head around than just two. Similarly, citizens across Europe will elect a parliament of 751 with no presidency at stake this May 22-25. The following numbers put this lack of voter interest in non-presidential elections on both sides of the Atlantic into focus:

Though very different animals, the U.S. midterm elections and the EU parliamentary elections have low turnout in common. That said, these numbers prove that it's Europe, especially Spain, that can teach American campaigners a thing or two about voter turnout. So why do European political fanatics love following American campaigns, but the most Americans can't be bothered with the European campaigns? How can the Europeans make campaigns sexier? Is it necessary?

A sexier campaign might generate more interest in the press and campaign activities, such negative advertising and grassroots voter mobilization, are specifically designed to generate more turnout. Candidates and political parties have a responsibility to bring their campaigns closer to voters, but not all parties have an interest in higher turnout rates that tend to benefit political parties on the left.

Emotions:

The psychology professor, Drew Westen is the author of the book, The Political Brain, and has done excellent work looking into why people vote the way they do, which has nothing to do with rational self interest. We affiliate with candidates, political parties and campaigns based on emotions, and the top two emotions that spur political action are anger and fear.

You've got to know voters in order to connect with them; and Europe's challenge is that it's a conglomeration of radically different cultures, languages and challenges. Former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, Tip O'Neill, famously declared that "All politics is local." This is true in Europe, especially a Europe in crises, and especially a Europe where citizens still very much identify with their own countries.

A feeble attempt at a Europe-wide campaign this cycle is the ridiculous video on the European Parliament page titled "This time it's different," which doesn't give any compelling emotional reason for this presumptive difference. It ends with the meaningless tagline "Act. React. Impact." The could vasty improve this video by pointing out what citizens should react to and how exactly they might act on that.

Having an enemy is important, because it elicits anger in voters, which gets them to the polls. On the other hand, happy voters don't get up off their sofas. There's already a precedent in Europe of making EU elections a referendum on the sitting president of any given country. U.S. Republicans are gearing up for the 2014 campaign by tapping into fears about the Affordable Care Act, otherwise know as Obamacare. In this, they have a great enemy to exploit both in the policy and in President Obama's weak poll numbers.

This is why negative advertising is so persistent, despite the fact that everyone says they hate it: It's a mechanism to rile up citizens to go vote against the perceived enemy. This same information, if true and well documented (as it should be), may serve to suppress votes on the other side as well. Democrats have set their sights on the Koch brothers, the wealthy donors fueling Republican campaigns across the country. Any Democrat who really understands the U.S. campaign system is very angry about both the recent Supreme Court ruling and the one in 2010 that have flooded the system with private cash, much of which is anonymous.

One potential EU-wide enemy is the pending transatlantic free trade agreement, otherwise known as the TTIP, but it would take a lot of courage for a political party to come out against it. Both American and EU citizens know very little about this agreement, not to mention that free trade always sounds like a good thing. If any political parties do chose to delve into the details of the deal and make an enemy out of it, they'll become good prospective enemies of those who support free trade. Hot button issues such as abortion and marijuana legalization make good rallying cries or enemies to mobilize voters.

We vote for people:

Most political candidates aren't Obama or Clinton or Reagan, and parliamentary elections face the added challenge of lists of candidates. What could be less exciting than a long list of somewhat faceless politicians that might make the cut depending on their position in the list? Again, all politics is local, and even though most parties in Spain are presenting lists that were chosen by the party leadership, they can make better use of these individuals by building local campaigns around each them instead of spreading the one at the top of the list too thin. This puts a local face on the campaign that people can connect to.

Furthermore, the person at the top of the list isn't necessarily the most compelling candidate. If they are, then they should be front and center, but if not, the focus needs to be on others who have the presence and the personal stories to move the party's base of voters in their respective communities. If they don't have the ability to mobilize a community, then they don't belong on the list.

Voters identify with people and their personal stories, which ideally pack some emotional punch. Storytelling was a critical best practice from the Obama campaign, and not just Obama's personal story, but the stories of local volunteers and how they came to be part of the campaign. Sharing stories is how we connect through shared values. These best practices work equally well, if not better on the local level which is critical for parliamentary and mid-term campaigns.

Ground game:

Winning is sexy and the only way to win an election is by getting more votes than the opposition. What the 2012 Obama campaign taught us was that the ground game -- the mobilization of voters -- can make up for what the candidate lacks in appeal. In 2008, Obama had practically had no need for his spectacular campaign apparatus, but in 2012, he was a mere mortal. The 2012 Obama campaign's voter turnout operation was as flawless as they come and bolstered by big data updated in real time by an army of well-trained volunteers. Like negative advertising, this effort wasn't aimed at changing minds, but merely increasing turnout among voters who favored Obama but had a low propensity to vote.

Spain's political parties don't have to build these networks of volunteers from the ground up, like the Obama campaign did because they already have nation-wide networks of volunteers to tap into: their militant members. This is the great, untapped resource of Spanish campaigns. The chain of command, the local leaders, even offices are set up already. But instead of making it clear to militant members that their job is to help the party win elections, the parties tend to keep these folks an arm's length out of fear of losing some measure of control over their campaigns.

Money talks:

Finally, the elephant in the middle of the room is U.S. campaign finance, which is completely private and less and less restricted as opposed to Europe's publicly funded campaigns. There's just more money swishing around American campaigns which doesn't necessarily make them better. Governor Jerry Brown of California reiterated that lesson in 2010 when he beat Meg Whitman who outspent him 10 to one. Nevertheless, private financing, combined with intense lobbying efforts corrupts the U.S. government: The average congressperson spend 60 percent of their time raising money and these donations buy access. Private campaign finance would surely be a step in the wrong direction for Europe.

Spain's and Europe's political parties can and should develop truly compelling and sexy campaigns that citizens can feel part of in a meaningful way. The majority of the laws that effect the day to day lives of European citizens aren't written and passed by their national governments but by the European Parliament. The lion's share of spending on lobbying by the world's most powerful corporates goes to Brussels. What happens there matters and political parties need to run campaigns that reflect this.

The Spanish language version of this article was published in the foreign policy magazine, esglobal.