Shanghai, the world's largest city by population and China's global financial center and transport hub, is the symbol of a rising China. The name of the city in Chinese translates as "upon-the-sea." The city grew in importance during the nineteenth-century due to European recognition of its favorable port location and economic potential. Following the British victory over China in the First Opium War, Shanghai became one of the Chinese ports open to foreign trade. As a center of east-west commerce, the city flourished. Shanghai's famous Bund, the commercial district that occupies the elevated bank of the city along the Huangpu River, became a symbol of European might.

In the oldest park in Shanghai, Huangpu Park, was a sign that read: "No dogs and Chinese allowed." This infamous sign, at the entrance to a decidedly European-style park, has made a huge impression upon the Chinese people in the city - especially among young people. This sign was featured prominently in Bruce Lee's 1972 film, First of Fury. Lee is denied entrance to the park by a turbaned Sikh guard as a European woman with a dog on a leash strolls past him. The guard points to the sign telling Lee: "You're the wrong color. Beat it." Just to make the point, the guard tests his truncheon on his left palm, and a group of Japanese in traditional dress mock Lee.

Lee, fighting to defend China's honor against foreign aggression, smashes the offensive sign to smithereens with a single well-placed kick. The only problem is that this sign did not exist.

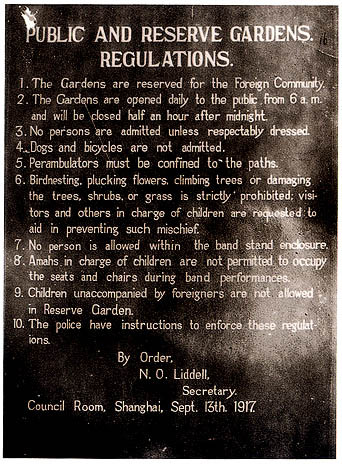

A period photograph from 1917 lists ten regulations, the first of which reads: "The Gardens are reserved for the Foreign Community." Insofar as dogs are concerned, the fourth regulation says "Dogs and bicycles are not admitted." Humiliating as these regulations are, they are far from the offensive wording Chinese inevitably recite that equates Chinese and dogs in the eyes of the foreigners.

Photo Credit: Photographer unknown, Shanghai, 1917. Photo in the Public Domain, en.wikipedia.org

So why, nearly one hundred years later, are Chinese so utterly convinced of the demeaning wording of this sign? Why has it entered and remained so firmly entrenched in the national psyche? And what does it mean for today's US-China relations?

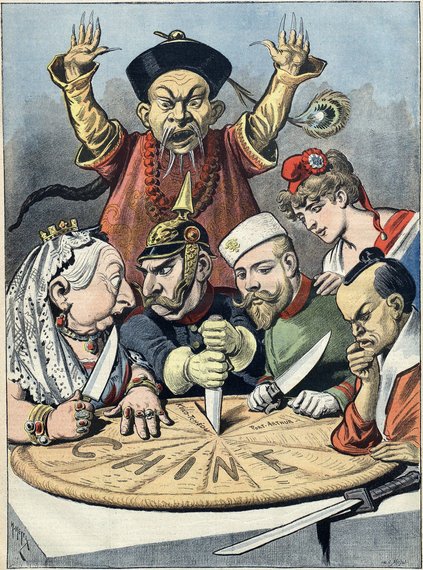

Chinese nationalism is a nationalism of resentment. It is based upon what the Chinese call the "Century of Humiliation," a period that began in the mid-nineteenth century. This was when Western powers and Japan forced a series of treaties on China after joint invasions and the Opium Wars. China was carved up into spheres of influence by foreign powers.

Picture Credit: Henri Meyer for Le Petit Journal, 16 January, 1898. Courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France.

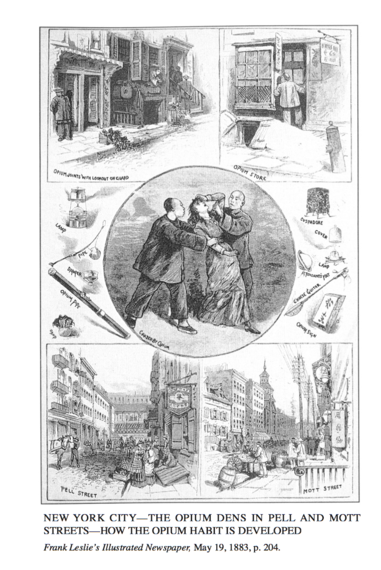

The result of these treaties, which the Chinese refer to as "waste paper," was that China had to cede Chinese territories to foreign powers. Along with ceding the island of Hong Kong to Great Britain, the treaties came to include some eighty treaty ports where foreign sectors were built on the edges of existing port cities, and enjoyed legal extraterritoriality. Foreign churches, clubs, racecourses and gardens sprang up in these cities. Chinese were effectively barred from sections of their own cities. And the Chinese aren't the only ones who are confused about historical facts surrounding this period. An informal survey of my students at a well-respected New York City university revealed that the majority of them did not know that China fought on the side of the allies in both world wars. More shocking, a good number of them thought the Opium Wars were waged to keep the evil Chinese drug from reaching American shores. These beliefs were fed by lurid tales of Chinese opium dens and white slavery in America.

Picture Credit: Artist unknown. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 19 May, 1883. www.macaulay.cuny.edu

Many of my students were stunned to learn that some of America's well-known families who amassed fortunes in "the China trade" (think Forbes) actually traded in opium. Like ingrained stories of foreign persecution against Chinese that engendered the myth of the Huangpu Park sign, Americans retain a negative view of Chinese as weak, drug-trading and corrupt people who must be dealt with using force, when necessary.

Picture Credit: Artist unknown. British Opium Clipper "Water Witch" built 1831. Collection of the National Maritime Museum, London. www.portcities.org.uk

So, what can be done to correct or overcome these negative beliefs held by citizens of the globe's two most powerful nations? And how is it possible that this generation of Millennials, with so much access to information, continues to harbor stereotypes and resentments that have their roots in the nineteenth century?

A good first step on our part would be both more and unbiased news coverage on China. Here's where it gets interesting. News delivery is changing for this generation. Print and analog are fading quickly in favor of digital delivery via hand-held devices--perhaps like the one you're holding now. And going beyond the news that is reported is now just a couple of keystrokes away. Readers can marshal data from a variety of information from online sources to arrive at better-informed opinions, more quickly than ever.

What is troubling is that American news organizations generally lump news on China in the Asia Pacific subcategory. This category includes Japan, Korea, India and Southeast Asia. But there is no dedicated space for news, features and entertainment on the world's most populous country (1.3 billions souls) and emerging superpower. Does this reflect a lack of interest? Is it a prejudice? Or does it just reflect a lack of awareness?

As the balance of world power is shifting, news delivery is also shifting. Those shifts, in tandem, will inform the shape and flavor of the future. And they're just a few keystrokes away, starting now.