Two of my favorite books are The Austrian Mind and The History of Underclothes. I'm sitting with both in front of me as I think about concerts I heard across this past New York Winter -- especially in the just-started Hungarian Echoes festival by the New York Philharmonic.

The Austrian Mind is William M. Johnston's epic, readable tour of the intellectual world of Austria-Hungary between 1848 and 1938. It's subtitled An Intellectual and Social History, and offers a world that glowed with the intensity of an exploding star as the Habsburg Empire passed from the 19th to 20th centuries and vanished in World War One. This is all personal to me. The maternal side of my family came from that world. One of my earliest memories of myself as pre-journalistic pest was peppering my grandfather with questions about that war in which, as a one-time Austrian cavalry officer, he lamented being "on the losing side."

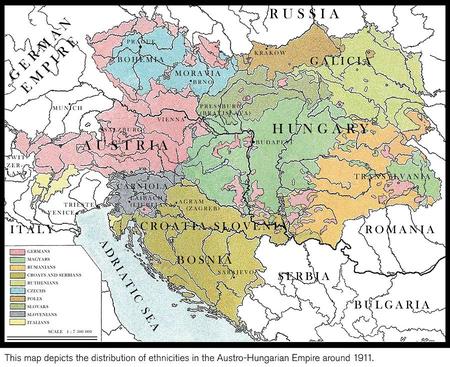

He rode his Joey, a horse named for Emperor Franz Joseph, across the Eastern plains and woods of Hungary, Galicia and Romania -- imperial lands whose nationalistic fervor had simmered for decades. In this country, too, he rode a succession of Joeys. The name sustained an irreverent homage to the monarchy, armored with irony after his flight from fascist Europe. As a kid, feeding Joey sugar cubes, I loved saying the beautifully friendly, American-sounding name.

What interests me in Johnston's book is how Habsburg remnants linger in the ideas and artistic moods that one experiences even now. Which brings me to the underwear book -- and will lead back to music. Written by a pair of writers named C. Willett and Phillis Cunnington (they were related; I don't know how), it follows the evolution from the 15th Century (of undershirts, breeches, nightcaps, corsets, etc) to the 20th. It also observes revolutionary change, describes how "diaphanous garments" exposed "a new and remarkable attitude of mind, very remote from the Victorian."

We're still curious about rebellions against imperial power, be they Victorian or modern -- or postmodern. The authoritarianism of forms, political and aesthetic, draws artists like red flags draw bulls. Challenging power -- even as a memory -- has sex appeal.

All winter I followed this half-hidden thematic outline, composers directly historical in their connection or influenced by the many changes in Central Europe. Maybe rebellions in the Middle East focused me on it, disruptions of old loyalties and styles. It started with pianist Jonathan Biss's fine recital on January 21. He played Janáček's little-performed Sonata L.X, 1905, with the insurrectionist title "From the Street," memorializing the death of a Czech protester against Austro-Hungarian hegemony. In 1905, Janacek witnessed the young man's murder at the hands of an Austrian soldier.

Three days later, I heard the East Coast Chamber Orchestra open a program in the increasingly well-attended Music Mondays series at the Advent Lutheran Church at 93rd Street and Broadway with Janáček's Suite for String Orchestra. Its transparent textures deliver a profound force that isn't overtly political -- though separating the composer from his Moravian political consciousness is impossible. Really, my Central European concert season didn't start with a haunting performance January 15th of "Evocations of Slovakia," by Karel Husa, at a chamber music evening at Symphony Space on 95th Street. Husa's balance of austere folk-cultural strains with a modernist aesthetic -- clarinetist Richard Stoltzman, violist Steve Tenenbom and cellist Marcy Rosen gave an authoritative performance -- was deeply influenced by Bartók.

I imagined my own festival: Janáček, Bartók, Husa. It will end along with the NY Philharmonic's season, in June, with a much-anticipated staged performance of Janacek's "The Cunning Little Vixen."

Between now and then, I plan one or two more posts musing on this region and its contemporary traces. I will wonder out loud at the weird ubiquity of work by the Transylvanian-born György Ligeti in New York these days. Bartók's work is being paired with Ligeti's throughout the Hungarian Echoes concerts being conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen in Avery Fisher Hall. The Ligeti thread was picked up by Jeremy Denk's electric Carnegie Hall performance on February 16th of the composer's dizzyingly polymorphic Etudes. Denk paired the 13 very different, linked pieces with the Goldberg Variations, raising questions about the breadth and shape of the variations literature over the sweep of time. I think one could justifiably call the Etudes 13 variations on freedom -- explosive torrents of power giving way to lyrical stillnesses that have their own virtuosity.

The work of György Ligeti, left, is being featured by the New York Philharmonic in its Hungarian Echoes festival. His Etudes were played by Jeremy Denk, right, at Carnegie Hall in February.

The Ligeti etudes wore titles, like "Autumn in Warsaw." But the music was more poetic -- meditative or jazzy -- than programmatic. I heard a distant affinity to Janáček's poetically political "From the Street," which wasn't program music, despite its name. I might have placed Ligeti's Etudes next to it, in my personal festival. Hungarian Etudes opened with a thrilling performance of the Ligeti piano concerto by Marino Formenti.

And that would be in my festival, too. My program notes would note that Ligeti was born in 1923, five years before Janáček died, seven after a Russian bullet wounded my grandfather. He grew up in the interwar years, decades locked into a sequence of dictatorships (Hitler, Stalin), a general period -- can this be overlooked? -- in which young people exchanged the last imposing corsets for silky camisoles, sought "degrees of denudation."

In Janáček, Ligeti, Bartók and Husa, we hear the brilliant agitation of different lives that spanned the 20th century, composers bent on independence of feeling, of method. About 12 years before Ligeti was born, that earth-shaking Viennese Arnold Schoenberg unveiled his impulse to create a new musical language, sweeping away Victorian orders more forcefully than anyone, affecting the young Bartok and countless others.

Mahler's big presence in New York this centennial year of his death also adds layers to a look at how music from a crumbling empire and its aftermath seems to be getting more of a hearing in 2011.