Media carries culture with it. The narratives and stories that move our culture end up in the discourse of our media. What makes media studies so fascinating is to watch the changes in our culture problematized, challenged and affirmed. Of course there's a problem in assuming that "Modern Family" or "Will and Grace" is the end-all, be-all in discussions about gender and sex politics. (One of the best academic paper titles I've seen was "'You Wascawy Wabbit!': Transgender in Bugs Bunny.") In academia, we can be guilty of taking these media messages too seriously. But I think that more often, in our society, we don't take our media seriously enough.

Media carries culture with it. The narratives and stories that move our culture end up in the discourse of our media. What makes media studies so fascinating is to watch the changes in our culture problematized, challenged and affirmed. Of course there's a problem in assuming that "Modern Family" or "Will and Grace" is the end-all, be-all in discussions about gender and sex politics. (One of the best academic paper titles I've seen was "'You Wascawy Wabbit!': Transgender in Bugs Bunny.") In academia, we can be guilty of taking these media messages too seriously. But I think that more often, in our society, we don't take our media seriously enough.

In the religious landscape, one of the most interesting changes in our society is the growing number of "Nones" -- people who are unaffiliated religiously but may still believe in a God, a higher power or have beliefs often associated with a religious institution (read here for the famous Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life report). Yet at the same time, my observation is that among those with religious convictions there's a greater pride in that faith than in the past.

Two books I've read recently are emblematic of this -- "The Hunger Games" by Suzanne Collins and "Christopher" by David Athey, a former professor of mine. Both are excellent books and both present a cultural narrative.

The Hunger Games was a guilt read. I never see a movie prior to reading the book -- except this time. And the book was compelling. The characters come to life and the dystopian world displays the realities of war on children in the context of a future America. Each year in this world of Panem, young adults are selected from across the country to fight to the death for the purpose of maintaining peace and creating a brutal, popular reality show.

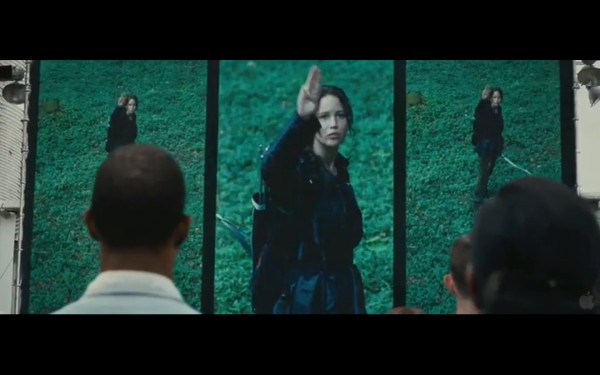

Yet one thing a number of bloggers (here and here) have noted is the absence of religion in the book and the series as a whole. Yet there are noteworthy ritualistic actions that occur during the plot of the book. For instance, the crowd holding up three fingers when the main character, Katniss, takes her sister's (Prim) place in the Hunger Games.

A shift has occurred since I stepped up to take Prim's place and now it seems I have become someone precious. At first one, then another, then almost every member of the crowd touches the three middle fingers of their left hand to their lips and holds it out to me. It is an old and rarely used gesture of our district, occasionally seen at funerals. It means thanks, it means admiration, it means good-bye to someone you love.

A similar scene occurs in the death of a key character in the first book. This scene could be read as emblematic of a culture that still has the elements of a religious culture after the religion is forgotten --perhaps similar to doing the sign of the cross without understanding what means or receiving Ash Wednesday ashes without practicing the penance incumbent in the ritual. (For more on the "spiritual," not "religious" aspects of the movie see here and here).

Whereas religion in "The Hunger Games" is subtle or nonexistent, the religion of "Christopher" is overt. The story is coming of age story; it has the feel of a quest, with three Catholic girls and the beauty of Midwestern nature serving as guideposts. Motivated by his love of Catholic stories (and a healthy appreciation of Catholic girls), he confronts the challenges of a world of doubt and fear.

In one conversation, Christopher meets Terra's grandfather (Terra is girl No. 1), who provides the religious roots to everyday phrases Christopher uses without knowing the reference.

In one conversation, Christopher meets Terra's grandfather (Terra is girl No. 1), who provides the religious roots to everyday phrases Christopher uses without knowing the reference.

"Happy holidays, Professor."

"Happy holy days, Christopher."

Then later, "Goodbye, Professor."

"God be with you, Christopher."

In the section below, Christopher is outside a love interest's house and begins to see nature as a guidepost for his quest. Here the religious element is artful and overt.

After each visit, Chris would linger around the backyard and the lake, strolling along the beach of shiny pebbles, allowing the convergence of cool air and warm air to kiss his skin more alive. The boy wished the girl could be outside with him, but she had afternoon prayers to say with her grandfather. It was a rule, and also something that she loved. Chris didn't understand the saying of prayers. His family never spoke of the Father, Son or Holy Ghost. Strolling along Superior, beneath the treetops shining like day-candles, the boy allowed himself to feel the heavens...without really having to face them.

Granted these are just two images, but they do speak to a striking dichotomy in American society that the Pew numbers denote: the presence of narratives that may or may not have a religious root and the presence of a thoroughly religious narrative.