NEW YORK -- For years, the city and the state of New York commissioned reports about the dangers of rising sea levels combined with a powerful hurricane. And for years, dissuaded by the costs of doing something, New York put in place few new preparations for a massive storm surge.

Now we have the first glimpse of the costs of doing nothing: at least 97 deaths in and around New York City, and $33 billion in damage from Hurricane Sandy in New York State alone, according to Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

Next time the damage done in dollars and in lives could be far worse. At its peak, Sandy was only a Category 1 storm. Its winds never went above 90 miles per hour near New York. Were something like a Category 4 storm, with winds of 131 to 155 miles per hour, to make landfall near the city, the devastation would be awful.

Many more would die. Houses would be toppled over by sheer windforce, subway tunnels could be flooded for months instead of a week, and the economic capital of the United States could be paralyzed. The city would incur $500 billion worth of damage, according to a 2006 analysis by the Department of Homeland Security.

As the climate continues to change, the damage could be even worse. According to a 2007 report by Risk Management Solutions and the University of Southampton, by 2070 the New York area will have 2.9 million people and $2.1 trillion in assets exposed to coastal flooding.

Here are some of the proposals to protect against the next Sandy.

BUILDING BIGPerhaps nothing has captured the attention of the public and politicians like the massive storm surge barriers that the Dutch have. But such barriers, near either the Verrazano bridge or the outer harbor between Sandy Hook in New Jersey and the Rockaways in Queens, would not be cheap: a full system could set the government back $15 billion. Meanwhile, the potential for such barriers to disrupt the harbor's ecosystem has yet to be studied.

While politicians like New York City Council Speaker Christine Quinn seem to be intrigued by the concept of a straightforward engineering solution, experts caution that the barriers are no silver bullet.

"The Dutch approach has been in some ways mistranslated into 'let's build a fort,'" said Samuel Brody, a professor at Texas A&M University who studies the costs of destroying wetlands and other natural protections against storm surges. Just weeks before Sandy, he spent time in the Netherlands inspecting the protective system there.

"If we build a fortress, people are going to want to build behind it, and in places like Texas and New York that can be a real problem -- it exacerbates development," Brody said.

BUILDING SMALL AND SMARTThis is where things get tricky: the best way to protect a house on the waterfront is not to build the house in the first place. But people like to live near the water, and they don't like the government telling them they can't.

Approximately 375,000 people already live in New York City's evacuation "Zone A." If Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Quinn, both of whom have strongly supported waterfront development, have their way, more will join them there.

But in lieu of putting more people into hurricane evacuation zones, the city could limit development. That might raise the costs of housing elsewhere. So Quinn has suggested the city should pursue stricter building codes in low-lying areas.

Brody said that taking measures like raising a waterfront structure and lifting up its electrical equipment typically adds about 10 to 20 percent to the cost of a house.

"SOFT EDGES"Instead of big storm surge barriers, landscape architects intrigued by natural protections against big storms, like sand dunes and marsh islands, have proposed a system of "soft edges" around the city's perimeter. A system of reefs, artificial islands and oyster beds could blunt some of the damaging force of waves from hurricanes. Catherine Seavitt Nordenson, an associate professor of landscape architecture at the City College of New York, has suggested that would cost hundreds of millions instead of the billions for storm surge barriers. (Since some water would still be allowed to enter the city, critical infrastructure like highways would also need to be storm-proofed.)

Work on "soft edges" has already begun. In Jamaica Bay, for example, marsh restoration is an ongoing process. The city has promised to spend $100 million to upgrade waste treatment plants there, stemming the release of harmful nitrogen into the water. The city will also spend $15 million directly on stopping the marsh islands, which can act as sponges during storms, from vanishing into the water.

Those islands, said Don Riepe, regional director for the American Littoral Society and a Broad Channel resident, "can hold some excess water so they can make it less damaging in the height of the storm surge."

But ultimately, he said, along the bay, "nature is just eroding what basically was not there in the first place. It's fill sites."

The first floor of Riepe's house on the bay was flooded during Sandy. He is keenly aware that climate change will eventually make living on coastal areas like Broad Channel an impossibility, even though his house, built in 1910, has "survived quite a few storms."

"I'm going to have to leave here eventually," he said. "My hope is either I die first or I sell the house and get out."

SEA WALLSA sea wall, which sits right on the water's edge, is a much less ambitious proposal than a harbor storm surge barrier. On New Dorp Beach in Staten Island, which was nearly leveled by Sandy, residents had been pleading for years for a sea wall. How much one would have helped is unclear, since on the night of Sandy sea walls were easily topped in Lower Manhattan. But New York Sens. Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand have asked the Army Corps of Engineers to restart a stalled proposal for one on Staten's South Shore as part of a larger $1 billion proposal for post-Sandy protections.

BEACH FILL, ELEVATING SAND DUNESIn Coney Island and the Rockaways, two areas hit hard by Sandy, the Army Corps of Engineers was already working on protecting against wind and wave. At the tip of Coney Island, Sea Gate, the Corps has concrete plans for a $25 million beach fill project. And since 2004, it has been studying ideas for elevating the sand on beaches in the Rockaways. It needs another $1 million to complete that study, and estimates that it will then cost between $20 and $100 million to actually provide permanent protections.

HARDENING THE GRIDThe failure of the New York region's electrical grid during Sandy resulted in unknown but vast losses in economic activity. In New York City, Con Edison could move crucial equipment above the floodplain and install submersible switches. Price tag: $250 million.

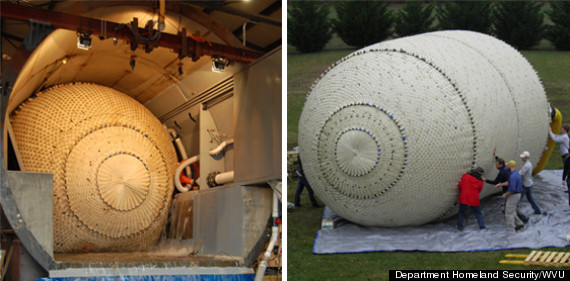

SEALING OFF THE SUBWAYSA wide range of solutions have been offered to protect New York's vital subways: from simply raising ventilation grates to prevent water from seeping in (a project the Metropolitan Transportation Authority has already begun, at the cost of millions); to giant inflatable stoppers to protect underground tunnels (which would cost perhaps $400,000 a pop); to storm walls.

How much would a system integrating all those protective measures cost? So far the MTA is not speculating.

"Honestly, we’re still tallying the costs of rebuilding what was damaged last month, and we haven’t even begun to figure out what a dream protection system would look like, much less what it would cost," the authority's spokesman, Adam Lisberg, wrote in an email.