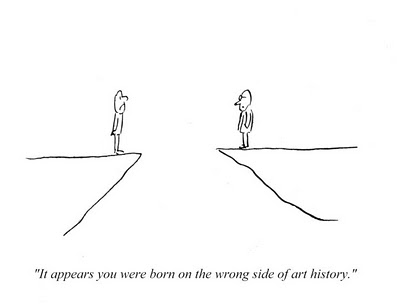

Image courtesy of "Artoons" by Pablo Helguera

Several years ago I was invited to lunch by the faculty of a large college. They wanted to talk about how we could encourage students from the small college where I teach to transfer to their institution. The meeting started out cordially enough, but I almost choked on my chicken salad when one professor made the following stern pronouncement: "If your students don't deconstruct, don't send them here."

In the awkward silence that followed I realized that I was essentially the bastard at a family reunion. After all, I don't deconstruct myself, even though I do have some vague ideas about what the word means. How, I wondered, would I make it through dessert without letting on that I wasn't dedicated to Derrida or fluent in Foucault?

If I slipped up, I might ruin the future of some of my students who would be tainted by their connection to me: the charlatan who didn't teach them how to deconstruct.

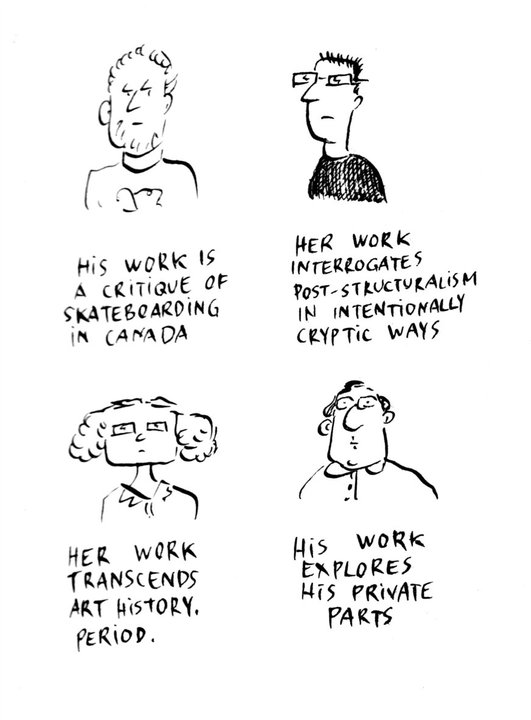

Image courtesy of "Artoons" by Pablo Helguera

When I was in college -- the late 70s -- my studio art professors said next to nothing about theory, but they had quite a bit to say about spontaneity. After all, being spontaneous meant being unconstrained, an appealing idea at the time. It also provided a connection to the revolution in American painting that had been brought on by Jackson Pollock, the action painter. That revolution had hardened into an academy, and the academy spawned academics.

Because "Action Painting" had prevailed in the 1950's when they were young artists, my teachers felt connected to the idea that every brushstroke was a kind of liberating gesture, and drips were the tangible symbols of freedom. One of my friends actually remembers a critique from that era where each painting was judged in terms of having "good drips" or "bad drips."

Ironically, we were learning that we had to be "free," but learning to be free meant conforming to the values of the dominant style.

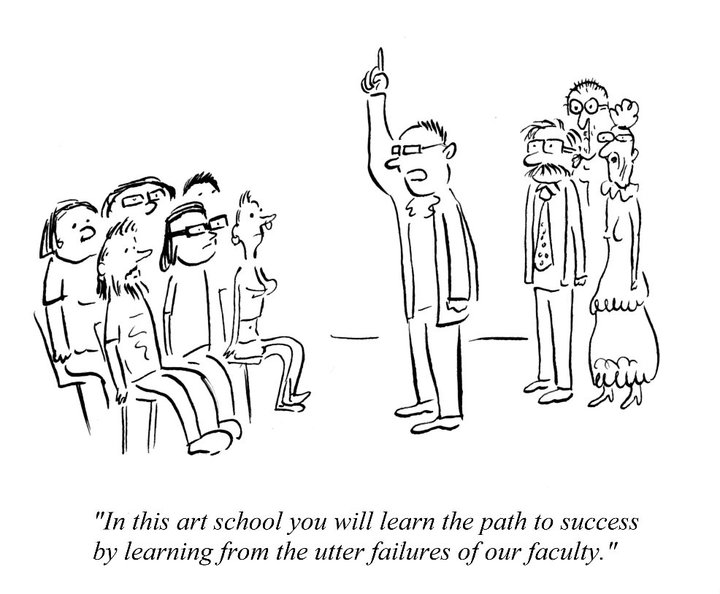

Image courtesy of "Artoons" by Pablo Helguera

The idea of that drip-based critique seems laughable now, but each generation of artists, professors and students seems to develop its own set of rigid rules and values. By the time I became a professor myself, in the mid-80s, freedom and spontaneity had been banished, along with technical skill. Technical skill had, of course, been discredited by the generation of artists that embraced freedom and spontaneity.

Postmodern theory, an intellectual approach to art making, had taken over. If you could handle it, you could be part of what was next.

When I taught art history at Art Center in Pasadena I would look over the student gallery and notice something that concerned me. Students with strong traditional rendering skills were majoring in Illustration, while students in Fine Arts made works that required intellectual theory. Some of them may have had skill, but they generally hid it to avoid being sent to the Illustration Department, a demotion in rank.

Being able to "deconstruct" requires speaking and understanding a certain type of language, and subscribing to certain intellectual theories. People who are comfortable deconstructing converse in a language I call "artspeak." Artspeak is -- for contemporary artists, curators and critics -- what Latin was for Medieval priests: an esoteric language that separates and elevates.

I was recently reading an exhibition review on the Saatchi Online website, which opened with this sentence: "Cordy Ryman manipulates and reconstitutes an inherited visual language, defining himself in relation to it."

That is artspeak. Reading it, I felt that I had learned very little about Cordy Ryman or his art. Instead I felt that I was about to read a review that tried to justify an artist's work with words that had little real connection to it.

I am a big believer in pluralism, and am convinced that very compelling works of art can be made without conforming to any style or way of thinking. In my view there is terrific work to be found everywhere. When I first heard the phrase "Let 1,000 flowers bloom," I felt that it expressed an affection for pluralism, and I repeated the saying fairly often.

Later, I learned that the quote had come from Chairman Mao, who historians generally hold responsible for not just the Cultural Revolution but the murder and death of over 50 million Chinese. Add to that, Mao had talked about a hundred flowers, not one thousand:

"Letting a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend is the policy for promoting progress in the arts and the sciences and a flourishing socialist culture in our land."

Authoritarians, I have come to realize, sometimes pose as populists. Interestingly, Postmodernism is often associated with a "plurality of styles," something that more authoritarian academics seem to have forgotten.

So, I don't talk about 1,000 flowers blooming any more, but I do take an interest in all forms and styles of art. I have seen plenty of Postmodern art that I appreciate, even if I am not conversant in the language that often accompanies it.

It does seem to me that the artists Donald Kuspit calls "New Old Masters" haven't been written about as much or as well in the past decade as they should have been. Maybe that is because artspeak doesn't apply very well to their work, which consistently demonstrates high levels of skill.

Skill, which is about practice and the mastery of techniques over time, doesn't deconstruct well. It also connects to long standing values and traditions, something that can cause problems for artists who want to be part of a vanguard.

All in all, my intention is to write about works of art and artists simply because I like them. The human being behind every work of art interests me quite a bit, but the categories, schools of thought and doctrines that they might be connected to really don't. I take the approach that the Dalai Lama suggests, looking for what I have in common with people -- and artists -- before I consider how we might differ in our views.

I actually made it through the luncheon pretty well once I composed myself. After dessert I noticed a "construction" that had been left from an earlier critique, and I knew just what to say: "The overtly lyrical variations of scale create a plastic ontology of form."

I may not deconstruct, but I am a pretty good mimic; a weed who knows how to look like a flower.

I keep in mind that over the long haul all styles are period styles. Each style is a carefully cultivated garden that a new chairman will want to uproot when the next Cultural Revolution comes along.