This is the second installment of a three part article tracing the evolution of extremist movements in Islamic history and analyzing their etiology and perpetuating factors. The first part described the impact of the Mutazila-Ahl Sunnah rivalry on the Islamic religiopolitical paradigm. In this article the utility of Hanbali scholar Ibn Taymiyya's teachings and religious rulings to latter day exponents of sedition and persecution is studied.

Taqi al Din Ahmed Ibn Taymiyya was born on January 22, 1263 in the ancient Mesopotamian village of Harran to an Arab father and Kurdish mother. Haran corresponds roughly to the village of Altinbasak in modern day Turkey. His father and grandfather were Hanbali scholars and religious teaching was considered a central part of the family heritage. When he was six years of age the Mongol invasion reached his village and his family had to flee to Damascus. This incident left a profound impression on him and may have influenced some of his most important decisions as a religious jurist.

The excellence of Ibn Taymiyya as a religious scholar was established early in his life. By the age of 19 he was acknowledged by his peers to be proficient not only in Hanbali theology but all extant schools of Fiqh. By the age of twenty-five he had written at least ten theological manuscripts and was renowned for his fiery brilliance in debate-as well as for his tendency to antagonize other scholars. Taymiyya was from the outset something of an enigma. While he remained mostly faithful to Hanbali teaching he did not confine himself to one school of thought and adopted an eclectic approach to formulate a theology that he asserted would restore Islam to its "original form". His early disagreements with contemporary scholarship revolved around the issue of the attributes of God and the "createdness" of the world. Taymiyya preached that God's attributes were those that the Quran and Ahadith mentioned and that ascribing attributes other than these amounted to apostasy. He rejected the philosophical envisioning of God espoused by the Mutazila that utilized the Aristotelian concept of a "first cause" or "prime mover" as well as the Mutazilite "theology of reason" which in his opinion was essentially the replacement of divine laws with man-made ones. He attacked also the idea espoused by contemporary philosophers like Ibn Sina and al Farabi that the world "emanated" from God and was one with Him, declaring it heretical. He saw this idea reflected in the Sufi teaching of "Wahdat-ul-Wajud" (oneness of existence) which he also labeled heretical. Taymiyya spent much of his scholarly life attacking Sufi and Shia teachings; while he stopped short of declaring them non-Muslims he taught that they had introduced "bid'ah" or innovations in religious matters and thus polluted the original spirit of Islam. The commonly held notion that he passed "Tafkir" or excommunication from Islam on Sufis and Shias is erroneous; however, his teachings have been utilized to justify persecution of these groups.

Taymiyya's relationship with the Mameluke Turk leadership (under whose reign he spent his life) was turbulent and ultimately dependent on his usefulness to them. The first friction came when he was asked to rule on an accusation of blasphemy against a Christian man in 1293. When his ruling of a death sentence was overturned by the Governor of Syria who issued a pardon in return for a repentance and apology, Taymiyya rejected the pardon and protested with many of his followers. This act of insubordination resulted in a prison sentence, the first of many punishments Taymiyya was to receive for his defiance.

A change of fortune arrived however, with the three attempted invasions of "Bilad al-Sham" (literally "land of Syria"; contained present day Syria with parts of present day Jordan and Lebanon) by the Mongol Ilkhanid dynasty.

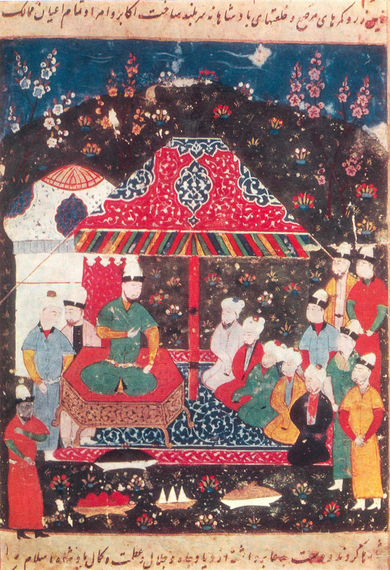

Mahmud Ghazan became the leader of the Ilkhanid dynasty in 1295 after executing his cousin Baydu Khan. On the encouragement of a Muslim Mongol Emir who helped him effect the coup, Ghazan converted to Islam. Immediately after consolidating his rule Ghazan turned his sights on Bilad al-Sham which the Ilkhanids had been unsuccessfully attacking since the fall of Baghdad in 1258. With his new found status as a Muslim, Ghazan attempted to gain the support of the people of Damascus and issued a letter to them presenting himself as the rightful leader of Muslims and describing the Mamluke Sultans as irreligious and corrupt. Disturbed by reports of troops refusing to fight the newly converted Mongols the Mamelukes enlisted Ibn Taymiyya's help. Over the next few months Ibn Taymiyya issued three "Fatwas" (religious rulings) regarding the Ilkhanids. Most important of these was the second Fatwa. Thirty-five pages long, it focused most pertinently on the validity of the Ilkhanid practice of Islam. Taymiyya began by bemoaning what he claimed was the undue influence of the "Rafidah" (literally "rejecters"; derogatory moniker for Shias) on the Ilkhanid leadership. He concluded further that since the Ilkhanids continued to follow many aspects of "Yasa"-the Mongol pagan tribal code-even after converting to Islam they were in effect apostates and in his view, deserving of being put to death. This ruling helped the Mameluke Sultanate greatly and it was able to lift troop morale and successfully thwart two major attacks by the Ilkhanids. The second of these was a decisive defeat of an eighty thousand strong Ilkhanid army aided by crusaders south of Damascus in 1303 which ended the threat posed by the Mongols to Bilad al-Sham.

The importance of Ibn Taymiyya's second fatwa cannot be overstated. It was the first instance of a major religious ruling endorsed by Muslim political leadership which declared killing an opposing faction of Muslims to be lawful. It is also the first instance of a Fatwa declaring a group of Muslims to be non-Muslims due to theological deviation. In the case of the Ilkhanid invasions it is important to bear in mind that the Mameluke were defenders and not aggressors in this instance and that the Mongols had since the days of Genghis Khan repeatedly broken treaties and engaged in unprecedented slaughter and pillage. There was much at stake. Also important to bear in mind is Ibn Taymiyya's personal trauma at the age of six. That the Mongols were responsible for uprooting his family from their ancestral home and causing years of hardship would not have been lost on him while issuing this Fatwa; he even brought this childhood incident up within the text of his second fatwa.

After a brief period of prominence and elevated status emanating from these fatwas, Ibn Taymiyya fell out of favor with the Mameluke leadership again. In 1305 he was sent to Cairo and held at the citadel there . Several more imprisonments followed, primarily around squabbles with Shafi and Sufi scholars, refusal to compromise on any of his views and an insistence that all other scholars conform to his teachings. Ibn Taymiyya died while imprisoned at the Citadel in Damascus; even during this last incarceration he continued to write prolifically, completing his last book.

The precedent of Ibn Taymiyya's second fatwa against the Ilkhanid Mongols has been repeatedly evoked by subsequent religious and political leadership to justify wars of aggression, sectarian persecution and political intrigue. The eighteenth century Nejd (present day Saudi Arabis) scholar Mohammad Ibn Wahab evoked Ibn Taymiya in his teachings. Wahab provided religious legitimacy to Mohammad Ibn Saud in his conquest of the Arabian peninsula and parts of modern day Iraq through a formal pact between the two to bring Islam back to its "purified" form in the region. Wahab utilized Taymiyya's attack on Shia and Sufi theology to justify Ibn Saud's attack on Karbala, the destruction of Shia and Sufi Mausoleums and relentless persecution of the two communities that continues to this day in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

The writings of twentieth century Egyptian writer Syed Qutb were heavily influenced by Ibn Taymiyya. Qutb evoked Taymiyya's second fatwa in making a case for rebellion against the Nasser regime in Egypt as well as other corrupt leadership in the Arab world. According to him like the Ilkhanid Mongols, Arab leadership had renounced the fundamental precepts of Islam and it was now lawful to overthrow them through force. Within Qutb's rhetoric and the brutal suppression of the Muslim Brotherhood by Gemal Abdel Nasser may lie the explanation as to why pro-democracy movements in the Arab world have so often donned a religious mantle.

Osama Bin Laden and Ayman Al-Zwahiri drew heavily on both Syed Qutb and Ibn Taymiyya in formulating Al Qaeda's case against Arab leadership and what they saw as the Western masters and enablers of this leadership. Both quoted Taymiyya in their speeches and cited him as an example of theological correctness and perseverance in the face of persecution.

Mohammad Yusuf, the founder of Boko Haram claimed to subscribe to the teachings of Ibn Taymiyya. In 2002 when he established the headquarters of the group in Maiduguri in Eastern Nigeria he ordered the establishment of a Mosque which he named "Markaz Ibn Taymiyya".

No other terrorist organization however has quoted Ibn Taymiyya more than ISIS. In their perfectly maintained online propaganda journal "Dabiq" they have cited Ibn Taymiyya frequently, using his rulings to justify their own actions. From the targeting of Shia Muslims and Yazidis to capital punishments for apostasy ISIS has repeatedly evoked him to justify their atrocities through their official mouthpiece publication. It is important to note that there are gross misrepresentations of Ibn Taymiyya's teachings in ISIS propaganda. Taymiyya laid out very detailed rules of engagement that included not harming children, women, the old, the infirm and those who surrendered. However in Taymiyya's harsh approach to other sects, blasphemy and apostasy ISIS has a convenient pool to tap into to justify their actions to those with little to no knowledge of Islamic theology. As repeated eye witness accounts have shown, this ignorance is characteristic of the majority of ISIS recruits.

ISIS has mentioned Ibn Taymiyya in almost every instalment of "Dabiq" and refer to him as "The Great Sheikh". For example, in Issue 4 of "Dabiq"he is referenced as approving of the enslavement of "apostate" women during war to legitimize the enslavement of Yazidi women. In Issue 8 Taymiyya's second fatwa against the Mongols is cited, this time to justify the killing of of those sects that ISIS deems deviants from Islam and therefore apostates. A quote from Ibn Taymiyya was also included in the video of Jordanian pilot Muath al-Kasasbeh being burnt alive.

In the final analysis, the teachings of Ibn Taymiyya became a tragic milestone in Islamic history when they were used and popularized by the Mameluke Sultanate in their defense of Bilad al-Sham. This precedent has provided a religious cover for many a demagogue and destructive leader in pursuit of power, territory and wealth. Through the dissemination of these teachings and the veneration of Ibn Taymiyya as a religious jurist they have also inspired and inflamed the persecution of minority Muslim sects, especially Shias and Sufis as well as followers of other religions.

The third part of this article will trace extremism through modern times to its current complex presentation.