I have been writing about looking, and how to take the time to see the world around you. The first few columns have been about paintings, especially Mondrian and Titian. But I promised from the beginning that I would be looking at many other things, from sand grains to moth's wings. The editor of the Arts page has very generously given me permission to talk about things that aren't art.

My theme, so far, has been paintings that take a long time to see. I think there are some works of art that take years to see, and some--like the painting of the weeping Virgin I wrote about in November--that require an entire lifetime of close looking and thinking.

One thing that may happen if you spend a long time looking is that you may learn nothing, or at least nothing you can put clearly in words. Patient looking is not usually a puzzle-solving activity: you don't "solve" a sunset or a painting. Looking, after all, is not reading. The poet Keats had a wonderful expression for this state of mind: he called it negative capability: the capacity "of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact & reason."

For me, patient, close looking is not the same as mysticism: it's not a kind of irrationalism, and it is not always indebted to Romantics like Keats. Slow looking is a way of attending to the fact that seeing is not reading. Images are not messages.

So now I want to range outside of fine art, and look at many sorts of things. Not all of them take a long time to see. Some can be seen in a few seconds: it doesn't take long to look at sand. Other things cannot be seen for more than a few seconds. In a future column I want to describe how to see the blood vessels inside your own eye: they can't be seen directly at all, and they can't be seen for more than a few seconds before they fade away. (I'll explain this experiment, which is simple, safe, and painless, and also truly surprising if not frightening.) Some things can barely be seen, like the faint lights of the night sky between the stars. Other things are tremendously difficult to see, even though they may be right in front of you.

Birdwatchers know how difficult it is to tell one little brown bird from another (birders calls them LBJs, "little brown jobs"), and doctors know how hard it can be to spot slight anomalies on X-Rays. And some things are hard to see because they are so blindingly obvious. In a future column I want to write in praise of a wonderful book that's about to be published on how to look at the ridiculously simple comic strip "Nancy." (Imagine, an entire book on how to look at a comic that can be read by a three-year-old.)

I have all this, and much more, planned out: an entire tour of kinds of seeing, species of looking, types of glancing, glimpsing, staring, modes of gazing, sorts of visual hypnosis and fascination. Ways of looking at the world, art included.

This time my subject is ice halos, the scintillating circles of bright sparkling light that sometimes form around the sun. It may seem these have nothing to do with art, that they do not belong here on the Arts vertical. But looking is what visual art is all about, and looking is what artists do. In contemporary art there are hardly any boundaries left: art asks us to see, and acts of seeing are presented as art. That is important to me, because art and the visual world mix and mingle together. Art cannot be explained without understanding looking, and looking cannot be understood without knowing about art. I won't be searching for artists who depict moths' wings, ice halos, or sand grains: this project is about seeing, in all its forms. I intend to think about seeing, and I hope to make the experience of art and of everday life richer and more rewarding.

And why choose ice halos? Why not start with landscapes, faces, or bodies--things that are more common in art? Because ice halos are a spectacular example of our blindness. A typical ice halo is a bewilderingly awe-inspiring object, but it is not rare. It's just that we don't look. I was first reading about ice halos on a cold winter day in Baltimore. I left the library, and ran across the Johns Hopkins University quad, on my way home. It was a blindingly bright, bitterly cold morning. At first I was hurrying along, like everyone does in the winter, my face down, my eyes half-shut against the winter glare. But I was thinking of ice halos, and so, on a chance, I looked up, right at the sun... and I saw the most astonishing sight. Around the sun there was an enormous circle, which nearly filled the sky. It was so big I had to look up and down and around just to take it all in. The gleaming halo was nearly as brilliant as the sun itself, and together with the sun it made a colossal eye, staring down at me. I was transfixed. After a minute I became self-conscious, and I looked around to see if anyone was staring at me. No one had even noticed me, and no one saw the ice halo. They were all hurrying, as I had been, from one building to another.

Technically, ice halos are the exotic winter cousins of rainbows: both are caused by water suspended in clouds, but ice halos appear when the water has frozen into tiny crystals. The halo I saw in Baltimore is called the twenty-two degree halo. (It should have a more spectacular name, but that's science for you.) It appears mostly in the wintertime, when it is very cold and the air is dry, but as the picture shows it can also happen in warm climates, provided the clouds that cause it are high enough so they are made of ice. (The photo with the palm tree was taken in Los Angeles.)

The twenty-two degree ice halo is very large; it is a different creature from the aureoles and brownish-blue coronas that sometimes form just around the sun or moon. Twenty-two degrees is double the spread of your hand at arm's length, so the halo is a little overwhelming, as if it were somehow very close to you.

The twenty-two degree halo appears fairly often in the winter. Often the only parts of the circle that appear are the segments to the right and left of the sun, which are called the twenty-two degree parhelia, or "sun dogs." Next time you're out on a cold winter afternoon, and the sun is shining brightly through thin clouds, look left and right of the sun--two palms' lengths on either side--and more often than not you will see brilliant small spots of light. Sun dogs are usually little spectra, with all the colors of the rainbow, but in light metallic tints. ("Sun dogs" is another awful name: they should have been called "sun angels." Perhaps other languages have better words for them: if anyone knows, please tell me.)

In my experience, people miss sun dogs mostly because a winter afternoon sky, filled with high shining cirrus clouds, can be too bright to look at. But if you make a point of it, you will be amazed. Many times I've pointed out sun dogs to people who were looking at landscapes and just hadn't noticed them. There were two metal-peacock sun dogs floating in the sky the afternoon I was married, in August, off the coast of Ireland. No one in the wedding party noticed them, but for me they were like signs, lovely ornaments to the day. Once you see them, you're hooked. Rainbows have a soft glow, but sun dogs scintillate, and in an icy drab winter landscape they are often the only bright colors.

The twenty-two degree halo and its sun dogs are the common members of a whole family of ice halos. I have also seen the "sun pillar," a vertical line of light through the sun. It can shine all the way down to the horizon and even below it, so that it looks like it is floating over the ground. Sometimes the sun pillar ends at the bottom with another bright light, called the subsun. Subsuns float right at your feet, in front of the landscape.

From here, things get more exotic. In places where it gets desperately cold, like Alaska, Siberia, and Antarctica, the entire sky can fill with an outlandish filigree of lines and curves, like a lace doily or a silver spider's web.

In the middle ages and afterward, large displays of halos were thought to be divine signals, portents of war or fortune.

Even if you don't believe in heavenly signs, halos can be really disturbing to look at: it's almost as if God has written something in the sky, and it needs to be deciphered. It must be an uncanny experience to see the entire sky decorated with a pattern, as if it had been drawn on.

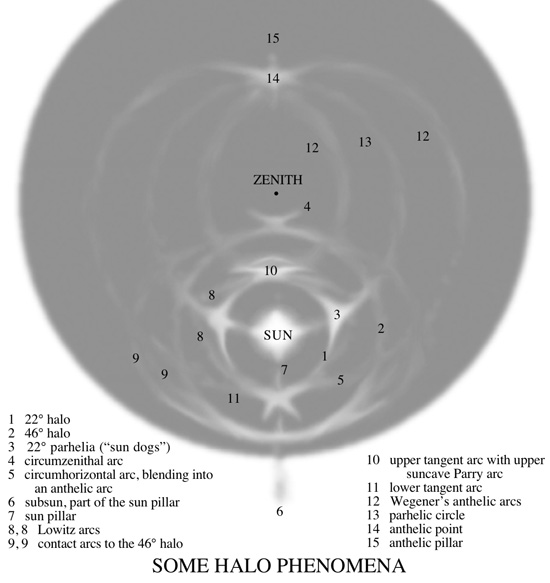

I have never seen anything like this, but I have thought of going to the Arctic or Antarctica just to see these halos. Here is a diagram I made showing some of these more unusual halos:

Here the twenty-two degree halo and the sun dogs are labeled 1 and 3. An especially lovely halo is the parhelic circle (number 13), a faint circle that passes through the sun, and continues around the entire sky at the same level, as if someone had painted a ring around the dome of the heavens. At the other side of the sky, away from the sun, there can be a bright spot called the anthelic point (number 14). Even more rarely, the whole sky overhead can be striped with other arcs linking the sun to the anthelic point (number 12). The anthelic point can even have its own sun pillar, called the anthelic pillar (number 15). Closer in to the sun there is a whole family of exotic little arcs crossing here and there: four Parry arcs (two of them blurred together at number 10), four Lowitz arcs (number 8), several contact arcs (number 9).

A number of physicists have worked on understanding ice halos, and in 1980 Robert Greenler wrote a book that explains virtually all of them. The twenty-two degree halo can appear whenever the ice crystals are shaped like little hexagonal columns. Sun pillars are made of light reflected off the top or bottom of thin, pencil-like crystals. Sometimes the light bounces around inside the crystals, following a complicated path of reflection and refraction. Greenler's book is a kind of scientific triumph: time after time he managed to program his computer (back in 1980!) to produce certain kinds of ice crystals, and the results are a perfect match for halos people had photographed in nature.

But in the end, it is a little sad to see nature explained so efficiently, so ruthlessly. My favorite parts of Greenler's book are the moments when he admits defeat. I don't mind the science: it's interesting, but it has very little to do with the experience of looking. Sometimes I read about the latest observations and research, and other times I am more interested in what Keats called negative capability: I suspend my desire to understand all these things in terms of hexagons, reflection, and refraction. I no longer believe that my fascination is answered by diagrams of ice crystals.

The twenty-two degree halo, and the sun dogs, are out almost every day in the winter. They are part of the world most of us grew up in, and yet most of us have never seen them. When I saw my first twenty-two degree halo, that day in Baltimore, I felt uneasy, as if I were being watched by a giant bright eye. Now I know those eyes are often in the sky. Sun dogs are interesting in a different way: it's as if the whiteness of winter has always been decorated with Christmas lights.

These are amazing phenomena, part of the world that is out there, waiting to be seen. They don't add up to anything, and they don't mean anything. But they show how we live our lives oblivious of even the largest, most spectacular things, and they fill in part of the empty sky with stunning sights. All we have to do is pause and look.

Next month: back to art, then on to comic books, photography, sand, moths, sunsets, and the inside of your eye.