Staying strong: It takes a lot of food to fuel Olympic athletes. Photo: U.S. Army/Flickr Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

Staying strong: It takes a lot of food to fuel Olympic athletes. Photo: U.S. Army/Flickr Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

If you see comments in the news and on social media about the environmental impact of the 2016 Rio Olympics, chances are it will be about transportation or the levels of pollution. All of the athletes, spectators and officials arriving in Rio via fossil fuel burning airplanes, spewing tons of carbon into the atmosphere. It's positively sinful.

While the opening ceremony sent a clear message about protecting the environment, there has been sharp criticism over the levels of pollution across the city and in Guanabara Bay.

With 480,000 tourists predicted to travel to Rio and more than 11,000 athletes participating, what about the food all of these people will eat? One could argue that these people would be eating anyway, however it is more challenging to eat in a sustainable way when travelling in a foreign country as you can only eat what's available.

The Rio organizing committee aims to provide food from traceable, sustainable and safe sources, favoring smallholder farmers and providing them with logistical support to transport their produce. In fact, the Rio Sustainable Food Vision Initiative was created in 2013 by a group of 20 institutions to maintain the sustainability of food for the country and the Olympics.

An estimated 14 million meals will be served throughout the games, producing 180,000 tonnes of CO2eq in Rio. While Rio is doing some token things for sustainable food, it's missed the opportunity to bring sufficient attention to this global issue that affects us all. Is this not something that should attract international attention and headlines around the world?

In some ways they are, it's just not widely talked about. In the Carbon Footprint Management Report Rio2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games, there is a brief section on reducing emissions from catering.

Transport represents 17 percent and energy 37 percent of greenhouse gas emissions globally. Our global food production system--which includes crop farming, raising livestock and deforesting lands to grow livestock feed and other crops, is responsible for about 25 percent of the greenhouse gases produced by human activity warming our planet. As human populations and incomes continue to grow, so does demand for meat, milk and eggs.

Across the world, scientists estimate that if agriculture were to conduct business as usual while other sectors reduced their emissions, agriculture's share of human-induced greenhouse gas emissions could double to 50 percent by 2050.

The biggest challenge however is that greenhouse gas emissions from our food production systems are probably the most difficult to estimate compared to other sectors.

You will often read that emissions from agriculture and forestry range from 21 percent to 31 percent. Deforestation, livestock and agricultural production are usually estimated to be 21 percent of global emissions. Add the share of emissions from transportation of products in the global food supply chain, packaging, and food waste, for example, and the global food system accounts for roughly 31 percent of global emissions.

There's incredible uncertainty on these estimates, especially for the most impacting food productions like rice and ruminant livestock, which both release methane and nitrous oxide, and have a far greater climate impact than carbon dioxide.

In its latest report, the IPCC has indeed been using emission values stemming from a single scientific publication for rice paddies and for livestock, the latter only considering ruminant species from temperate regions. Research shows that uncertainty on global rice emissions is of an order of magnitude of emissions themselves, and that in developing countries, especially Africa, emissions from livestock could have been overestimated by a factor of 10.

Somehow, someone has been cheating the figures about food, which the general public and media care much less about than their cars' emissions. Let's see why.

As reported a few years ago, fewer than half of young UK adults know butter comes from a dairy cow and a third do not know that eggs come from hens. Our education system is less to blame than our increasingly urbanized world where we have lost the connection with the agricultural landscapes that provide our food. We have too often let our kids believe that this all comes from the supermarket next door through some sort of industrial process, which is devoid of an animal or plant - let alone a farmer with a family.

It is now common for people to consider the climate impact of the mode of transportation they use, to the point that some pay to offset their CO2 emissions when purchasing an airplane ticket or booking a cab.

However, compensating for the climate impact of what we eat is much, much further away. Being able to realize this would assume an understanding that producing what we eat has required not only a transformation and transport process, but that food production has impacted the climate more, because it involves plants, soils and animals that all emit greenhouse gases.

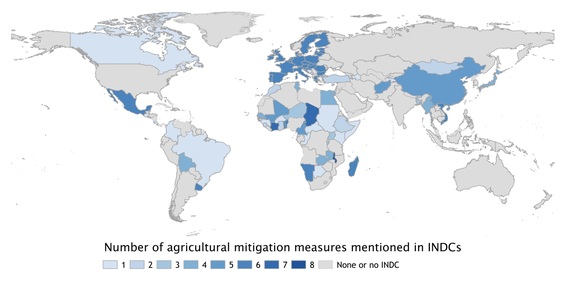

Fortunately, many countries have started taking emissions from our food system seriously. Of the countries that included mitigation in their Intended Nationally-Determined Contributions at COP21 in Paris, 103 included targets related to agriculture, shown in a study conducted by the CGIAR Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security.

As shown on the map below, mitigation is not a privilege of industrialized countries.

Clearly, massive investment would be needed in agricultural research to improve our understanding and provide a better estimate of agricultural emissions. At the UN Climate Summit in 2014, CGIAR announced it would need to dedicate 600 mUS$ per year to work on climate-smart agriculture, combining mitigation of agricultural emissions with helping 500 million farmers adapt to more stressful growing conditions.

What would it be compared to the $14.7 billion Volkswagen announced it would pay to settle emissions-cheating claims with U.S. consumers and regulators?

Isn't it simply that taxpayers and car buyers are eager to pay for less polluting cars than for less polluting food? Therefore, isn't there time to change the way we consider what we eat and the impact it has on the environment, especially on climate?

Wouldn't the 2016 Rio Olympics be an opportunity for that?