"Cobra!" the three-year old cried out, pointing to a soldier. Cobra was the southern designation for soldiers from the northern army in Congo-Brazzaville.

The soldier frowned and walked over to the boy and his mother. "You're lucky a truce is on," he admonished, "or I would kill that little future soldier of yours."

Roughly half of little David's three years had been spent during war. When the family first fled from their home, David often clapped with glee at the sound of gunfire or explosions. Relatives naturally urged his mother to keep him quiet lest he attract soldiers' attention. These fugitives were often exposed to dangers and disease. In one morning's dim light, it appeared to David's mother Médine as if he had grown a full head of hair overnight; she quickly discovered that it was instead a swarm of mosquitoes. On one occasion David was stiff and dying from severe malaria. Although Médine holds a PhD from France, she was a fugitive like everyone else from her town, and she had no money to pay the only available clinic. Nevertheless the owner, a family friend, gave David the last injection that he had left.

But now a truce had been established, and Médine and David had hope of a different life, even of coming to the United States. They would not be seeking refugee status, which is in any case difficult to obtain. (In recent years the U.S. has accepted seventy to eighty thousand refugees per year, yet displaced persons worldwide have reached some sixty million, or nearly seven-hundred fifty times that number; Refugee Admission Ceiling.) She was coming to the United States for a different reason: she was engaged to an old friend--me.

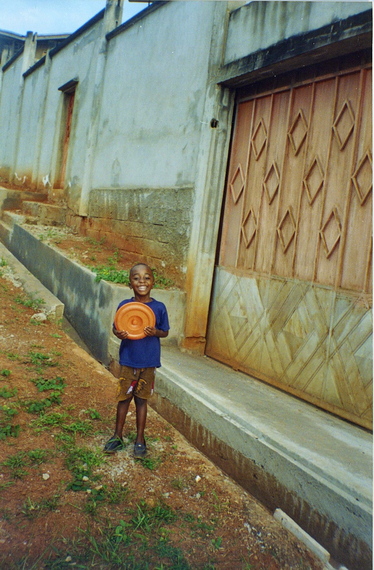

Most of the children from her neighborhood had died during the war, but her precious David had survived. Because David's genetic father had abandoned him before his birth, David wondered why he did not have a father. Now, however, Médine was able to tell him that he had a father. He quickly announced happily to a visitor, "I have a father who loves me."

We all underestimated, however, the difficulties of immigration. A fiancée visa should be a simple matter; at least at that time it was much faster than a marriage visa, requiring us to wait for our wedding. But war had closed the U.S. consulate in Brazzaville, so Médine and David needed to travel to the neighboring country of Cameroon. For that journey, she needed a valid passport, but the new government had invalidated the former government's passports, including the one that Médine had kept for eighteen months while she was internally displaced due to war.

While they waited in Pointe-Noire for a new passport, David fell sick with malaria again; Médine ran crying in the rain with his limp body to a clinic. Because she still had some of the money I had sent, she was able to buy the medicine necessary to save his life. Just before they left for the capital to check on the passport again, a storm blew off their shack's tin roof, drenching them as slugs floated above the mud floor below. Storms terrified David for a long time after that experience.

After we reunited in Cameroon, we discovered to our horror that a lawyer had forged one of Médine's documents; the nature of fiancée visas required me to return to the U.S., visiting Médine again only once she had the document. Médine had to return to Brazzaville, leaving David behind for his safety. David could not understand why we had to leave him with Médine's host family in Cameroon. "My Mommy is never coming back!" he cried each night. Finally, after several weeks, we all reunited again in Cameroon.

Immigration is not always a quick process, but for us it was further delayed by 9/11 and by an anthrax scare that shut down the Vermont Service Center. Although the immigration service faxed us their approval, the Consulate needed it by diplomatic pouch--which never arrived. The Consulate insisted that the Immigration Service had lost the file, whereas the Immigration Service insisted that the Consulate had lost it. Given reports from friends, the fault likelier lay with the grossly overworked Immigration Service, but for us it made little difference.

"I will come to Philadelphia with you tomorrow," David insisted to the end. Heartbroken, I had to warn him that he might not be able to come with me, since as a professor I would soon have to start my semester or risk losing my means to support us. "Who will play with me?" he pleaded.

As the Consulate informed us, just before my mandatory return to the U.S., that the official approval still had not arrived, I held David up to the window. "Can you explain to my son why he cannot come with me?" I had been teaching David English, but he didn't understand our conversation and simply smiled at the woman. She winced uncomfortably, but there was nothing she could do.

Alongside Médine's family, Médine and David had been displaced within Congo for eighteen months. But problems with U.S. immigration now displaced them, this time away from family, for eight more months.

David is now a well-adjusted music major at Asbury University. I am so proud of my son. But he went through more suffering in his first four years than many U.S. citizens experience in their first four decades.

Some voices today ignore the hardships that future residents of our country experience waiting for visas that already often take too long. That time is long especially for children for whom long waits may constitute a significant proportion of their lives so far. Concerns about terrorists among refugees are understandable, but do they justify traumatizing those for whom the United States remains a legitimate beacon of hope?

(I recount more of David's and Médine's experiences in our book, Impossible Love. I also recounted Médine's immigration experience briefly in Immigration Story.)