According to the bi-annual study by the London Zoological Society and the World Wildlife Fund, global wildlife populations have declined by 58% since 1970. Freshwater environments, lakes and streams and their surroundings, says the report, are the most damaged, with on average 81% of their 1970-level non-human animal life now missing.

Methodological critiques of the report - deeming its authors to have mashed vast and variegated data excessively into too few signal numbers - abound. But no serious biologist denies that we are in the midst of an enormous extinction event. "Event" is the proper term, although not all mass extinctions happen with one great bang, of the Asteroid-Dinosaur variety. For perspective, the rebounding of new life after a mass extinction takes millions of years. On that scale, the demise happening right now all around us is horrifically sudden.

To summarize the report cause-and-effect-wise: since 1970 we have doubled, crowding out, consuming, and otherwise destroying more than half of our closest relatives.

This week we begin the Torah anew with Genesis.

Far too commonly, when we think theologically, we regress not only into a pre-Copernican mindset, but into a pre-Darwinian worldview as well.

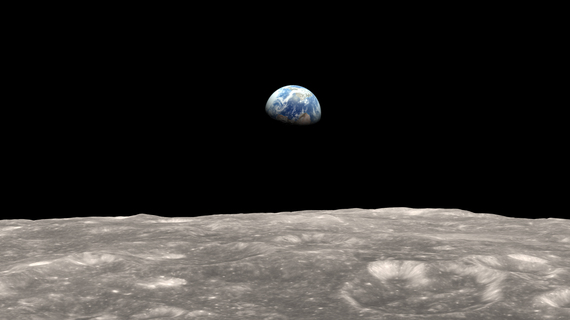

We tend, spiritually, to look up at the heavens much as our ancient ancestors did, considering all we see as the glorious backdrop for a main attraction down here on earth.

Perhaps even more grievously, we also tend to forget (or we never properly learn) that natural selection is not teleological. Evolution does not operate by targeting any predetermined end. The pressures of each moment and the materials available in it determine what will go forward and how - and these successive moments and materials are conditioned by the ones that come before them, not, as biologists would point out, by any definite foreknowledge of the moments and materials that will come after.

As biologist Ernst Mayr put it: to enquire "why" in evolutionary terms is not to ask "what for" but rather "how come."

Giraffes were not made with long necks so that they could reach the tops of trees. Rather, giraffe-like animals born with long necks fared better in their circumstances than short-necked siblings, and thus survived more optimally to breed with one another, and hey presto (eventually), giraffes.

This is a subtle but fundamental distinction - and it threatens to make a nonsense of such purposeful biblical and divine dicta as "Let us make a human being" (Genesis 1:26).

What spiritually meaningful story can we tell, in good faith, in our times - as we read our Torah anew this year?

Well, here is a try:

In the beginning of our cosmos there was an impulse to create that entailed in itself the possibility of everything that we know ever to have happened in this universe and everything that ever will happen.

In a moment of trust, or faith, or hope, or sheer insistence upon self-expression, such as human terms cannot possibly encompass, the impulse's Source - which from our vantage-point boggles the mind as the unfathomable No-thing before time - took a step into physical actuality.

It was an explosive step, a sudden tumult of existence perfusing in nanoseconds and over eons, roiling changing subatomic particles flying apart and then consolidating themselves, under governing variables co-evolving through a tug-o-war into something like stability, the resulting atoms coming together here and there, through vast expanses of being - as best as we can glimpse and fathom the beginning.

Everything was possible in that one first step - but only possible: in some instances, highly likely; in some, extraordinarily improbable. It would all depend on how things went, each frame of the filmstrip depending on the occurrences of each previous one. We know enough today not to speak of clockwork inevitabilities, but of clouds of possibility.

It is difficult to determine where we ourselves fall in the range of likelihood. What reckoning we can manage suggests that our species, capable of such contemplation, must be an extraordinarily rare being - which is saying a lot, considering the scale of the place, and of time.

Throughout enormous expanses of time and space, nothing much seems to happen at all. The universe is a nearly empty and almost uneventful expanse, a thin, loose web of substance and occurrence over gigantic tracts of darkness, of nothing we can see.

Here and there, bits of hydrogen get together and get interesting.

This has happened before, in several cycles, starting much earlier than the birth of our sun. The heavier elements we know today can only have been generated in supernova explosions, the demise of a previous generation of stars from a more undifferentiated time.

Our moment, too, will pass.

Meanwhile, where elements come together, possibilities multiply. Things happen. The ancient generative impulse tries on many forms. How does it go for them? That depends on so many things. Right here, right now - on this tiny planet, on the physical scale of our human hands, and at this juncture in the story of earthly life - the answer turns out to depend greatly upon what we humans choose to do, with our eyes open.

In that way, one of these cosmic moments is not like the others.

That is as mind-boggling and awe-inspiring a truth as any tale told in ancient terms of legend. Has such a thing ever happened before? Will it ever happen again? As far as we know, there is just this one chance for us to show what happens when it does.

It could be a sad and ugly story, where our part in the beauty and the survival of terrestrial life is concerned. Or it could be something else. "Let us create a human being," indeed!