I just read two sweeping reports on the state of income inequality in the U.S. (the second link focuses on state-level inequality) and other advanced economies. Perhaps it's because I've been so ensconced in fiscal cliff discussions, but I was struck by how much more alarmed policy makers are by the budget deficit than by the inequality situation. There are reasons for that tilt -- some good, some bad -- but based on magnitudes of the problem, it's far from clear that our current sole policy focus is warranted.

Findings:

The first link above finds the indispensable inequality researchers Piketty and Saez reflecting on the long income inequality time series data they and others have developed for the advanced economies. Their key findings are:

- The decline in income concentration in the U.S. over the great recession was due to cyclical capital losses, not a structural change in the underlying factors driving the trend. This can be seen quite clearly by a) taking capital gains out of the income data, revealing a steady upward trend, or b) by noting the increase in inequality (share of income going to the top 10% of households) in 2010, a return to trend.

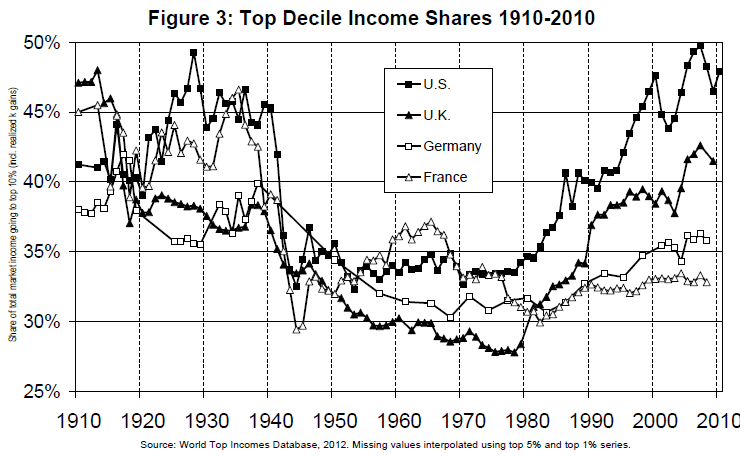

- The fact that different countries hit by the same globalization and technology advances show different inequality trends suggests an important role for political economy -- policies that affect the distribution of market incomes -- in these outcomes. In France and Germany, for example, the top 10% holds about 35% of national income; in the US, it's about 50% (see figure below). "Pure technology stories based solely upon supply and demand of skills can hardly explain such diverging patterns," write the authors, who argue that tax policies are a "promising candidate."

- As I've suggested in various posts, the authors agree that higher inequality may be associated with the debt bubble and bust from which we're still recovering, though they're not sure as to what's causation and what's correlation (they take solace in the Minsky-esque conclusion that "modern financial are very fragile and can probably crash by themselves -- even without rising inequality"). Me, I think in an economy where a) inequality steers growth away from the broad middle, b) credit is cheap, under-regulated, and securitized such that there's distance between originator and final borrower, and c) as the boom progresses, risk become underpriced -- well, that's a recipe for the shampoo cycle (bubble, bust, repeat) with inequality at the core of the model.

The second paper -- from researchers at EPI and CBPP -- is also part of a valuable series ("Pulling Apart," or PA) that tracks income inequality by states over time. Some findings that caught my eye:

-The story above re credit taking the place of paychecks is partially motivated by real declines in average incomes, as the wedge of inequality diverts growth to the top of the scale. That dynamic is evident in the PA data -- see, for example:

On average, incomes fell by close to 6 percent among the bottom fifth of households between the late 1990s and the mid-2000s, while rising by 8.6 percent among the top fifth. Incomes grew even faster -- 14 percent -- among the top 5 percent of households.

In every state plus the District of Columbia, incomes grew faster among the top fifth of households than the bottom fifth. Nationally, the richest fifth of households enjoyed larger average income gains in dollar terms each year ($2,550, after adjusting for inflation) than the poorest fifth experienced during the entire three decades ($1,330).

By looking at rising inequality through the lens of state data, the authors offer up state-level policy ideas that will help, like raising and indexing state minimum wages, more progressive state taxes (e.g., by reducing reliance on sales taxes versus income or property taxes), and better coordinated safety net and health care programs. This last bit is particularly timely given the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. The states that accept and implement the Medicaid expansion and move aggressively to set up the health care exchanges will be providing a great service for their citizens on the wrong side of the Gini coefficient.

So, what does all of this have to do with the fiscal cliff and budget deficit? Since the early 1980s, deficits have averaged around -3% of GDP with a pretty big variance, -5% in the mid-80s, +2.4% (surplus) in 2000, as high as -10% during the great recession, and about -7% and falling now.

On the inequality side, since the early 1980s, according to Piketty and Saez, we've transferred 15% of national income from the bottom 90% of households to the top 10%.

Which of those is the bigger economic deal? If you ask any DC policy maker what's the most important challenge facing the nation, they'll tell you it's the budget deficit. Yet a compelling argument can be made that a shift of such magnitude in national income from the bottom 90% to the top 10%, and the commensurate problems it presents -- the growing gap between growth and the living standards of the middle class and poor -- is, in fact, at least equally, if not far more, worthy of their attention.

The deficit and the debt are highly sensitive to growth. Even in the fiscally irresponsible and not-great-growth GW Bush years, the deficit to GDP fell to about 1% in 2007. If we manage to get a balanced plan in place that includes some new revenues, once the economy begins to grow again, the near term deficit will diminish. After that, it's all a question of slowing health care spending, and that's an existential question not just for the budget but for the whole economy, meaning we have to crack that nut no matter what.

Inequality, on the other hand, can and likely will keep growing, as Piketty and Saez's data suggest, unless policy measures intervene. I've discussed such measures in lots of past posts -- see here, e.g., re full employment and the role of economic slack in growing inequality. Piketty and Saez's arguments for higher tax rates on those at the top of the income scale are clearly worth keeping in mind during our current fiscal negotiations. And the PA team's ideas about state measures would help too.

But it's hard to imagine much progress on this front if policy makers continue to obsess so exclusively on budget deficits instead of the income deficits experienced by the poor and middle class. Of course, many deficit scolds are motivated by anti-tax, anti-social insurance, and anti-government ideology, so they've got a vested interest in the status quo. And to be clear, I'm not suggesting we ignore the budget deficit. I'm just saying that here as elsewhere, a bit more balance is in order.

Source: Piketty and Saez, 2012, link above.

This post originally appeared at Jared Bernstein's On The Economy blog.