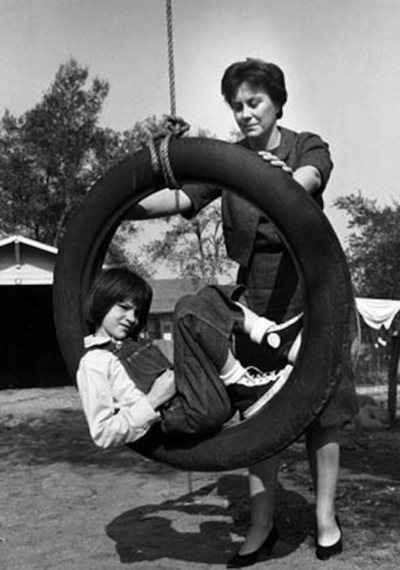

Mary Badham (Scout) and Harper Lee, on the set of To Kill A Mockingbird, Monroeville, Alabama, 1961. Via and © Leo Fuchs

"I shall probably write a book some day. They all do."

-- Nelle Harper Lee, 1947

This is not a review of Go Set A Watchman. On the eve of its publication, though, and following the issue of its first chapter, published last Friday, there's already much to consider.

To start, and to finish: Go Set A Watchman is neither a new novel, nor a sequel to To Kill A Mockingbird. It was written in the mid-1950s, and set then, too. It was then put aside, and left unrevised and unpublished by its author, Harper Lee, for nearly six decades.

While Lee was writing Watchman, Brown v. Board of Education (1954) said that public school segregation was unconstitutional. In 1955, Emmett Till was tortured to death and thrown in the Tallahatchie River by white men who were acquitted of his murder. Later that year, Rosa Parks stayed in her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. The immediacy of the civil rights movement informs Go Set A Watchman in ways that it does not, so directly, in To Kill A Mockingbird (1960). Though Mockingbird was written later, and Lee knew well what was happening in America as she completed it, she evaded contemporary times, after a fashion, by setting Mockingbird in the mid-1930s.

Nelle Lee, born in 1926, set out to be a lawyer, like her father and sister. She started law school at the University of Alabama, spent the summer of 1948 at Oxford University, and then declined to practice law at the family firm in Monroeville. She moved to New York City to write instead.

Go Set A Watchman begins with Jean Louise Finch, a twentysomething woman, on a southbound train, heading from New York City to Maycomb, Alabama. Amtrak's Crescent still leaves Penn Station every afternoon, passing through Alabama the same time, next day. You can take one of those sleeper cabins yourself, all the way to the Crescent City, New Orleans - I've done it. The passionate evocation of homecoming, from a settled urban area to the rural deep South, has been sung of in a hundred train songs from Hank Snow's "I'm Movin' On" (1950) to Johnny Cash's "Hey Porter" (1961) to the Allman Brothers' "Southbound" (1971). Lee makes it magical, with color and smell and all the senses involved - but with, from the first lines of Watchman, race and class to the fore:

"Since Atlanta, she had looked out the dining-car window with a delight almost physical. Over her breakfast coffee, she watched the last of Georgia's hills recede and the red earth appear, and with it tin-roofed houses set in the middle of swept yards, and in the yards the inevitable verbena grew, surrounded by whitewashed tires. She grinned when she saw her first TV antenna atop an unpainted Negro house; as they multiplied, her joy rose."

The unpainted houses are Negro houses, connected to the modern world by television antennae, contemporized thus, but still clearly distinguishable to Jean Louise.

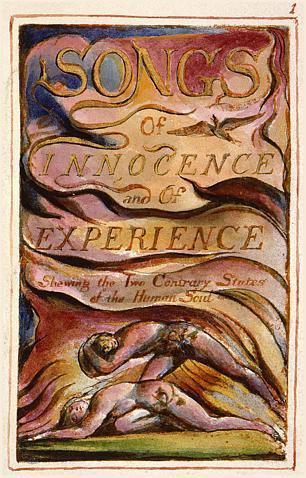

She wears "Maycomb clothes" at home that she doesn't wear in the city, but the black sleeveless blouse, gray slacks, and loafers seem more Audrey Hepburn in Funny Face (1957) than Jean Louise in Alabama to me. As she nears Maycomb, her head is full of literary allusion - to Southern poet and lawyer Sidney Lanier, to mid-Victorian decadent poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, and, most significantly, to William Blake's introduction to Songs of Innocence and Of Experience (1789). She muddles him up with William Cullen Bryant, but "piping down the valleys wild" is the first line of Blake's "The Piper." If To Kill A Mockingbird is Lee's song of innocence, Go Set A Watchman is her song of experience.

William Blake, Songs of Innocence and of Experience (Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul), via blakearchive.org

The words "Jean Louise's brother dropped dead in his tracks" made my heart turn over as I read them, until I thought, as well as felt. It's not an unnamed Jem Finch from To Kill A Mockingbird who has just died. It is a character who preceded him, and who Lee didn't create for this earlier manuscript. Lovers of Mockingbird may want to yelp in sorrow. Don't. Jem is asleep in his bed with a broken arm, Atticus beside him, and Atticus will always be there when Jem wakes up in the morning. Think instead of a young woman, approaching thirty, laboring over a first novel. I'd bet anything that Nelle Lee had read all of Virginia Woolf by the early 1950s. Here she is, trying to make a Modern novel - and disposing of a character the way Woolf does, with such craft, in To The Lighthouse. We have come to love Mrs. Ramsay, Prue, and Andrew. Woolf upends our ideas of the novel's century-old building bones, plot, setting, and character, as she disposes of all three characters in terse parentheticals: "[Prue Ramsay died that summer in some illness connected with childbirth....A shell exploded. Twenty or thirty young men were blown up in France, among them Andrew Ramsay....]" You gasp in horror; then you comprehend what Woolf doing, and gasp in awe. Lee is taking the same path.

Jean Louise, a New Yorker now - as was Lee was for more than a half century herself - tries to feel disconnected from where she was born, "Maycomb County, a gerrymander some seventy miles long and spreading thirty miles at its widest point, a wilderness dotted with tiny settlements [.]" About to arrive here again, Jean Louise thinks, "What had she done that she must spend the rest of her years reaching out with yearning for them, making secret trips to long ago, making no journey to the present? I am their blood and bones, I have dug in this ground, this is my home. But I am not their blood, the ground doesn't care who digs it, I am a stranger at a cocktail party." This passage starts off William Faulkner and ends up F. Scott Fitzgerald - from Caddy Compson in The Sound and the Fury, to Nick Carraway observing the other characters of The Great Gatsby. Lee casts herself solidly, in Watchman, as she does not in Mockingbird - confident enough, there, to slip off the stylistic power of the immediate past - as a High Modernist writer.

Henry Clinton, the young man who becomes a replacement son, and junior law partner, for Atticus is no suitable mate or match for Jean Louise. She's "almost in love with him," but almost is not quite, and she looks in a crystalline, Joycean short story of a paragraph at what life with Hank, now thirty and eager to marry her, would entail:

"The easy way out of this would be to marry Hank and let him labor for her. After a few years, when the children were waist-high, the man would come along whom she should have married in the first place. There would be searchings of hearts, fevers and frets, long looks at each other on the post office steps, and misery for everybody. The hollering and the high-mindedness over, all that would be left would be another shabby little affair à la the Birmingham country club set, and a self-constructed private Gehenna with the latest Westinghouse appliances. Hank didn't deserve that."

With a sigh of relief you can almost hear, Jean Louise determines that "for the present she would pursue the stony path of spinsterhood." What is revealed of Hank in the novel makes me rather glad of this.

I have avoided all the early pre-reviews of Watchman, except to see the mentions of Atticus Finch as a bigot and racist. There is a mix of outrage and approval at this: readers who love the Atticus of Mockingbird for his liberal championing feel bereft; readers who resented his liberal patronizing do not. The paternalistic "Reconstruction" specter of the South has a firm grip on Maycomb in the mid-1930s, and its long skeletal hand keeps an almost tighter hold in the mid-1950s, as the civil rights movement and a truer idea of justice for all became part of America's everyday, and fear of change and loss of prerogatives rattled the "leading citizens" of towns like Maycomb in real life.

It is a terrible misreading of Go Set A Watchman to claim that it recasts, transforms, or turns Atticus into a racist. This draft of a book existed before the character Atticus Finch, in Mockingbird, was begun. Lee wrote the Atticus of Watchman first. Then she set that work aside, revised, redrafted, wrote new things, and published another novel. Nothing has been done to the Atticus of Mockingbird - except by one's own imagination and feelings. He's not designed as a sequential character, like, say, Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes. Watchman is not a "new" novel; it is nowise a "sequel" to Mockingbird, nor even, really, a prequel. It is a rough draft that stands next to Mockingbird, connected like two halves of a medieval diptych telling connected stories with different images, in different ways. Watchman shows us things Lee rejected, reworked, and made anew when she wrote Mockingbird, not "what happened next."

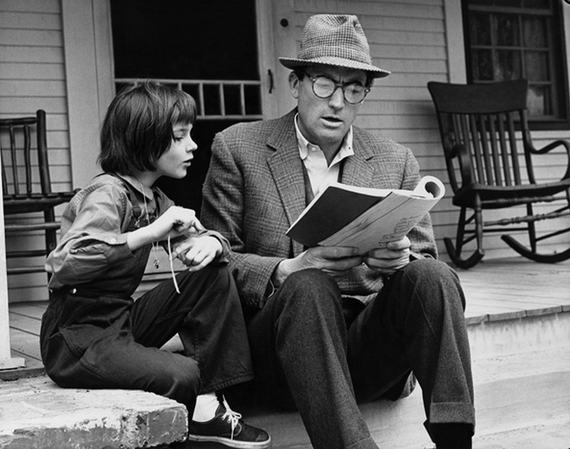

Mary Badham (Scout) and Gregory Peck (Atticus), on the set of To Kill A Mockingbird, 1961. Via and © Leo Fuchs

Whether we should be reading Watchman at all is a moot point, now. Did Lee intend to publish this nearly sixty-year-old draft, ever? For many decades, she clearly did not. Her big sister Alice, Nelle's best friend, protector, and lawyer, concurred. Alice Finch Lee died last November in Monroeville at 103. Just three months later, amid much fanfare, Lee's lawyer, agent, and publisher announced the forthcoming release of Watchman, and there has been increasing controversy since about both the sequence and chronology of the "rediscovery" of the manuscript and of the process by which it has come to be put in print. I hope to heavens that Nelle Lee, in the quiet of her room at the retirement home where she lives, desired and approved this publication without any pressure or undue persuasion. What is fact is that Watchman is now available to us, and cannot, whatever the circumstances leading to its publication, be unpublished, unread. So read Watchman, please do. Stand it next to Mockingbird, diptych-wise, and see, and feel, what both of them say to you, individually, and together. Talk about it. Write about it. Remember, though, that Watchman is a draft, unrevised by its author, and abandoned many decades ago; and Mockingbird, though set chronologically earlier, was written later, and not as any kind of continuation or sequel to the work Lee set aside. And, as you read, think of the celebrated cautions of two other Southern authors, Thomas Wolfe and William Faulkner. One warned us that you can't go home again; the other, that the past is neither dead, nor past.

*****

In 1947, the University of Alabama student paper The Crimson White profiled a literary law student thus:

"In case you've seen an intellectual looking young lady cruising down University avenue toward Pug's dressed in tan, laden with law books, sleepy and in a hurry and wondered who she is - she's Nelle Harper Lee....a law student, a Chi Omega, a writer, a Triangle member, a chain smoker, and a witty conversationalist. She is a traditional and impressive figure as she strides down the corridor of New Hall at all hours attired in men's green striped pajamas....Her Utopia is a land with the culture of England and the government of Russia; her idea of heaven is a place where diligent law students and writers ascend after death and can stay up forever without Benzedrine. Wild about football, she played center on the fourth grade team in Monroeville, her home town. Her favorite person is her sister 'Bear.' Lawyer Lee will spend her future in Monroeville. As for literary aspirations she says, 'I shall probably write a book some day. They all do.'"

Not all succeed. Nelle Lee, publishing as Harper, has now done so twice: first, with To Kill A Mockingbird, its sales in the hundreds of millions already; and now, with Go Set A Watchman, the presale orders for which have smashed prior records to bits. Lee deserves to be gleeful about this, and I hope she is. She, like Woolf, eschewed the family tradition of law, and chose to make stories instead. Salve, et ave, ma'am.

Anne Margaret Daniel 2015

* All quotations from Harper Lee, Go Set A Watchman (2015), © HarperCollins via Wall Street Journal

* Quotation from The Crimson White © University of Alabama; repeated in Kerry Madden, Harper Lee (Up Close), Viking (2009).