My news and social media feeds finally are getting over the furor surrounding President Obama's remarks at this year's National Prayer Breakfast. You remember: Last week the President dared suggest that Christianity, like Islam and other world religions, has blots on its record. After referencing ISIL/ISIS, he named "the Crusades and the Inquisition," and then "slavery and Jim Crow" as historical moments when Christian persons did not always behave in a Christian manner, to put it euphemistically. He spent more time joking with the Nascar driver Darrell Waltrip, a fellow speaker, than he did invoking the past and linking it to our present, but apparently no one was offended by his corny "Jesus take the wheel!" knee-slapper.

I still get a few indignant blips through my phone's alerts, though, and I admit that I remain troubled by much of the reaction to the President's comments. Of the four examples the President provided of Christianity's failures, the Inquisition has received the least attention. I'm not surprised by the predominant critical sidestepping; perhaps, like Erick Erickson of Redstate.com, many of the President's detractors see the Inquisition as "a Catholic thing, not [about] us Protestants." Yet of those four historical events, it is the one where the (paltry) critical response, and the event itself, reverberate with me. I would never have guessed that anyone might wish to defend, in any way, the Spanish Inquisition. In part, I wouldn't have guessed this because neither the Catholic Church, the Spanish government, nor any Spaniard I have ever met, seem keen to defend it themselves. But for every cause, there is a champion.

"There was no single 'Inquisition,' but many," explains Jonah Goldberg. "And most were not particularly nefarious." True as to the "misnomer" of a singular Inquisition, though I suspect the name functions as linguistic shorthand, just as "the White House" or "Wall Street" do. I also wonder who gets to determine greater or lesser nefariousness in the context of this event. Is this the judgment of survivors? I would love to read that memoir: "The Inquisition: It Wasn't So Bad!" Bill Donohue of the Catholic League, in his short piece "Obama Insults Christians," labels the Inquisition a "fable" and states categorically that "the Catholic Church had almost nothing to do with it." He then engages in a splitting-of-hairs parsing of religious and secular authority - over exactly "who burned the heretics" - that is astonishing in its mercenary quality. Astonishing, though not convincing, since Pope John Paul II apologized for Inquisition atrocities fifteen years ago. The pontiff included them in a sweeping mea culpa on behalf of the church, for its wrongdoing throughout the centuries. As a Catholic, I do indeed feel insulted - but not by President Obama.

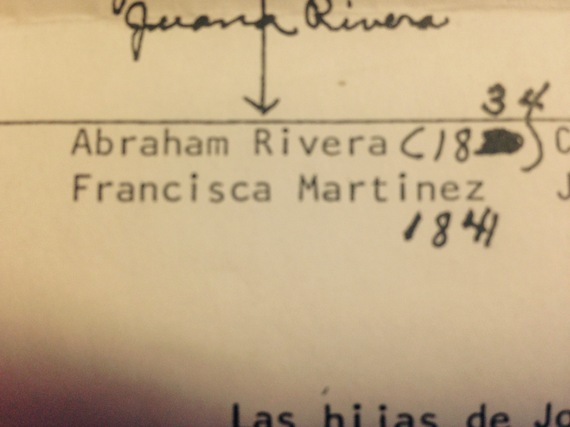

The Inquisition as "fable." That one gets to me, and breaks through my usual "eyes-permanently-rolled-back" reaction to the partisan nonsense infecting our country's political thought. Over the last few days, this word has brought me to the brink of tears several times. That is my family you so hurriedly push aside with this word, Mr. Donohue. In particular, it is my great-great-grandfather, Abraham Rivera, of Coahuila, Mexico. Abraham is the only member of my family tree with an Old Testament name, alone in a long list of Juans and Josés and Marías. It is Abraham, alone in that list, whose name crystallizes for my family what we have long suspected about our Rivera ancestors: That they were not always Catholic. That at some point in time, between 1492 and the twentieth century, they became conversos: Spanish Jews forced to convert to Catholicism, or risk death.

We have no hard proof of this, but then, that was the point: Forcing Jews to convert was meant to erase them from the social fabric, to transform the Jew into a bogeyman figure from a receding past. A fable. But this fable is my family: they breathed. They loved and had children; they worked and they died. They were real. And at some moment that went unrecorded, so that they might live, they ceased to be Jews. The reason why can be summed up in one word: The Inquisition. ***The heart of my family tree fills a single sheet of paper, compiled by my mother's oldest sister many years ago in the pre-Internet and Ancestry.com days. Her precise secretary's typing is embellished by her equally admirable cursive, as she added, scribbled, and penciled in later when names and dates came to her. Neither she nor any of her siblings knew Abraham. In a quirk of fate, I am descended from several youngest children and "late" babies, making our generation spans huge: Abraham was born in 1834, a full century before his great-niece/my aunt appeared. Thus, there are no stories about him, no funny anecdotes or heart-warming tales to pass around. There is just his name, and a general... idea about the Riveras as a whole.

We speculate about the kinds of jobs they held, and the skills they brought with them to Northern Mexico. We hypothesize about the region of Spain from which they came, in the much-fought-over, Moorish and Jewish South. We engage in musing about their name itself, sometimes Ribera or Ribero before it was standardized as Rivera. It seems like a converso name, we say, but is it a reliably converso name? Then the speculating, hypothesizing and musing trails off, met by a brick wall of no documents, no legal proof. Nothing, for instance, that would allow us to apply to Spain's current government, who have just passed legislation inviting the descendants of expelled Jews to return. Imagine it: Spain holding out an apology and citizenship to those it once tried to destroy.

But then, to counteract all of this pressing lack, there is Abraham. I can't say that it is an eyebrow-raising, freakishly uncommon name in Spanish. It's not as if his parents had named him Manzana, or Hiedra Azul. But it is nowhere near as common as the New Testament names and saints' names of which many Latino Catholics are enamored, and which otherwise dominate my genealogy. My name, María, appears everywhere. All of us - Riveras, Gómezes, Sánchezes, and Olmedos - seem to have been very fond of Juan and Juana, José and Josefa, Manuel and Manuela. Very fond. When we weren't recycling these cognomens, we were digging into the ancient past, so far back that I have to break out the Lives of the Saints in order to find a name's origin. (Another great-great-grandfather, Caralampio, clearly got his name from the early Greek Christian martyr Charalambos, since he was born on the saint's feast day. I mean, it was clear once I looked it up.) For the most part, my family tree is an unremarkable assemblage of the most common and unremarkable Spanish names - except for Abraham.

Actually, I take that back: It is an eyebrow-raising name. For the first time I saw the family tree my aunt made, I turned to her and said, "We have an ancestor named Abraham?" She just smiled.

Why would his parents call him Abraham, a name whose Hebrew connotations would have been unmistakable in his place and time? (Or as my own mother exasperatedly put it, "They practically put a target on the poor guy's back.") What could my great-great-great-grandparents see in early nineteenth-century Mexico, that I cannot? For I see a former colonial realm, New Spain, which let barely a generation elapse before establishing an office of the Inquisition on land still wet with Aztec blood. I see a government and church under the strict rule of a series of monarchs - beginning with los reyes católicos, Isabella and Ferdinand, and proceeding through their grandson, Carlos V, the last Holy Roman Emperor actually crowned by a Pope - fixated by ideas of a Catholic society free of Protestants, Muslims, and of course, Jews. Sangre pura, pure blood, writ large across oceans and nations. I see a papal line of demarcation, a Treaty of Tordesillas that finally, having been negotiated and wrangled by several popes and kings, settles which parts of the "New World" will be claimed as spoils by Spain and Portugal.

This is a world in which secular society, as we know it in the contemporary West, does not exist; rather, church and state work hand in hand. Lastly, I see a world in which anti-semitism flourishes, an old habit dying very hard. It remains even after Mexico successfully becomes independent, abolishes the Inquisition, and eventually allows practicing Jews to immigrate. Even as Isabella and Ferdinand's bones molder in a faraway grave, anti-semitism remains, its now deep roots allowing no give.

Perhaps what Abraham's parents saw is simply no longer there: a northern Mexico that was a frontier, full of open spaces and possibilities. Room for people to make their own realities, away from the settledness of the capitol. Perhaps, in between war with Spain and war with Texas and war with the United States and war with France -- so many wars -- his parents saw something like peace. And in that peace they decided to leave us, me, or those of us who may still come, a sign. Because being converso meant that to survive, my family would have to go underground. Be hidden, submerged, safe from the hateful furies around us. At some point, our Judaism became so hidden, so buried, that it didn't emerge again: the Riveras I knew were deeply devout Catholics, and their children and their children's children have been Catholic after them. The conversion was complete, and the old Riveras are gone.

I have no means of knowing whether Abraham himself was a practicing Jew, or whether his parents were. We have suspicions, musings, and hypotheses; decades of knowing suggestions, like my aunt's smile; and a name that is utterly singular in the all the branches of my family. So what I believe is this: I believe Abraham's parents remembered something, and they did not want that something lost.

Abraham's name tells me that when he was born, his parents decided that his name should be a message, a beacon to those of us yet to be imagined. A sign, as we jot down names and birth dates, that all is not as it looks; that we once had another history, even if it can no longer be seen. We once were Jews. Even if there was no Inquisition office in their hometown, no grisly execution or torture in the main plaza, it still radiated its power to terrorize throughout the land. Here I will borrow from President Obama's Prayer Breakfast remarks, though it may give offense to some: This is how the Inquisition is exactly like our modern scourge of ISIS. Spanish colonial powers didn't need to kill every possible Jew in the New World. They made a spectacle of those they did murder, burning alive mothers and sons, sisters and brothers, right in the Zocalo, the center of Mexico City. A shock to the system, meant to sicken and to make everyone else fall in line. And my family did. ***I return to the President's Prayer Breakfast comments, and read them again. His implicit linking of ISIL/ISIS with events from the past makes sense to me: I see the past in the present. It is there for all of us, for no one has a complete family tree. We all have something - someone - missing, though many of us may not know it. We are fortunate indeed, if our ancestors left us some sign, a light by which we can read what is not there.

The Inquisition is my history and it is my family's history. It is my hideous, cruel legacy as the descendant of Mexicans, of Spaniards, and of Indians, as the latest daughter of men and women who once were Jews. It is my ancestral gift as a Catholic - for they are also my people, and my people did this - and it is a gift for which I feel nothing but fury and shame. The President could compare the Inquisition to ISIS or the Crusades, slavery and Jim Crow; He could compare it to the Nazis, to Pol Pot, to Augusto Pinochet, to the Shah, to Stalin, to Trujillo, to those who butchered the 43, to whoever has brought misery in their wake, and I would not much care. Barbarity is barbarity is barbarity. Can you honestly not recognize it in all its incarnations, regardless of the face, name, or God it wears for a mask?

Abraham, I send you my love. I got your message. I will keep looking for the rest of our history. And I promise that when I find it, I will leave a sign.