I'd call Memories of the Revolution "invaluable" -- if only that word conveyed how exhilarating it is to read this new book, the inside story of the women's theater corps that infiltrated New York culture in the '80s, transforming it in ways that continue to resonate. Compiled by iconic East Village writer-performers Holly Hughes and Carmelita Tropicana and writer Jill Dolan, Memories' essays, fly-on-the-wall interviews, and play excerpts vividly re-create the early years of the WOW Café, where epic resourcefulness and sheer nerve produced works of audacity and wit. WOW's name should be legend to all who love theater that upends conventions, but most media missed their chance to recognize the revolution taking place at the intersection of brazenness and art. Hughes, one of the infamous NEA 4 who now teaches in Michigan, spoke with me about how it felt to start a bold new tradition and the shape of America's longest-running female theater collective today.

How did you first discover WOW?

I lived on St. Marks Place, and in the basement of the Catholic church was a space called Club 57 that was already kind of a famous venue; Eric Bogosian and Ann Magnuson did a lot of their early work there, and there was a Hasidic rapper who was a fixture... I went into this space, and there were racks of thrift-store clothes, every gender and every...you could have a sequined cocktail dress and a men's jacket, marching band -- quasi-military yet musical -- you're not really gonna kill anyone; you might deafen them. Suddenly the line between performance and audience was really blurry. There were kissing booths -- and Diane Torr, who was an early fixture at WOW, a Scottish artist who was a stripper and a feminist, a dancer [who organized] go-go girls. It was just an amazing world, and I wanted to be part of that world. A lot of feminist and lesbian spaces seemed to buy into the anti-porn argument, so this felt super intoxicating. I showed up at [WOW's] space on East 11th Street to volunteer, I looked around for who was in charge, and no one seemed to be in charge, so I picked the tallest person. That was Peggy Shaw. I wasn't sure she was not James Dean at that moment. I said, "I want to volunteer and work backstage," and she said, "So when do you want to do a show?" and I said, "No, I want to work backstage." But of course there was no backstage, there was no option of being off stage; you were always on stage. I couldn't refuse a direct order from a woman who might be James Dean, so I did my first show. It was four hours long [laughs]. The show was in no way good. But I was like, This theater, or whatever this thing is? I'm gonna do this.

So many of you worked day and night for nothing, to make art happen.

WOW survived as some sort of community because the genius of Lois Weaver and Peggy Shaw came up with a system that allowed us to cooperate with each other just enough to survive, but not so much to feel constricted. It was a scrappy, scrappy group of people, who were cantankerous and contrarian in a lot of ways, even as they were hungering for a sense of community. But we survived because we were so scrappy.

Reading the book I yearned to turn back time so I could have joined --

You, me and Cher! In a sense WOW was anachronistic, in that it was challenging a moment in feminism and lesbianism that was questioning pornography and representation of sexuality. WOW as a physical space was really the brainchild of Lois, Peggy, Jordy Marks and Pamela Cahme. Originally we presented, using the word present very loosely, almost any woman that had pitched a show to us. We had no money; we had a space, and we had a mailing list; we would do a split of the door. WOW sort of functioned like that, with some WOW members doing shows, but most of the work being done by people we might know well, or just any woman wanting to do a show about an abortion and her pet rock [laughs].

Women would wander in and you were open to all comers?

Pretty much. And that was just a recipe for burnout. Because people would be disappointed at what we offered, what we didn't have; they had higher expectations about what it meant to have a show there. Since they were passing through, a lot of times they were not respectful of the space, they would have a different sense of...

Entitlement?

Entitlement, or, you know, hope. [Laughs] I can't really blame them. But when we moved in 1985 to the space on East 4th street, we really shifted and became a company. With some outside artists, but mostly not.

If WOW were a men's troupe, it would have the legitimacy/iconic legacy of Charles Ludlum's Theatre of the Ridiculous. If I were HBO, Amazon -- any of the outlets hungry for content -- I would produce every one of the plays in the book; I just think the originality of the voices would speak to our "female-friendly" Amy Schumer/Broad City world.

Amy Schumer and Broad City are commercially targeted, and most of WOW was not, although people wanted to earn a living. The work of the East Village artists hasn't gotten enough recognition -- in part because a huge number of people died -- but to the extent that a lot of artists are known of that period, you're mostly talking about white guys. WOW was an important voice in all of that. There's still very few women calling the shots, even in experimental theater. American stuff is still really male and really white.

Did the interviews you did confirm your memories, or surprise you?

I expected to hear WOW was the first place where I felt like I could express who I was and be out about my sexuality and be an artist. That was a story I heard a lot. I didn't expect to hear I also felt like I had to leave part of my identity at the door. A lot of the Jewish artists I interviewed were like, It was really a goyishe place. And working class people felt like their experiences [weren't valued]. I [interviewed] somebody Jewish who grew up in the projects, but her mother was an artist, and she grew up having music lessons. That notion of living in the projects and having a culture-rich education was not familiar to me, growing up in the Midwest. But life is economically segregated. A lot of people from New York felt like they were invaded by people like me, and some people who came from the hinterlands, like me, felt the New Yorkers were not welcoming.

You've noted diversity was a challenge.

From the beginning the fact that WOW was largely if not entirely white was something we weren't happy with; it was an open question that was revisited continually. At the time it mirrored that gay life was very segregated. Mostly the membership of WOW was self-selecting: you came, you wanted to be part of it, you showed up and worked, and you were part of it. There were attempts to get some women of color involved; then I think the decision was made rather than rope some people who might have different priorities into your world, maybe we could use the resources of WOW, which were largely the space, to help [people] without a space. East Village Asian Lesbians hosted an event there on a regular basis; we also curated a couple of festivals and series, and we would invite women of color specifically. It wasn't a huge amount of producing, but we did some. Today WOW looks very different in terms of membership than it did in the '80s. A few people I would describe now as trans showed up in the early days, but the sort of language and awareness of trans identity wasn't there for most of us core members, although people were certainly playing with gender and thinking about gender performatively. Long after I left there were debates about the role of trans people at WOW; there was a period where there was a decision that it was gonna be women-born-women only. I think membership really dropped at that point. But now women of color and trans people have a significant presence... There are not a lot of people in my age demographic. It's difficult to sustain the kind of energy and commitment that something like WOW requires as you get older.

How divisive was the issue of men? Was it just a red herring trotted out to confirm stereotypes about feminists and lesbians?

WOW was never a separatist space -- but what that meant varied tremendously. One of the brilliances of WOW [back then] was if you had a show at the space, the space was yours, and you could make a lot of different decisions. When we experimented with presenting people, there would be women, sometimes straight women -- straight woman were always a part of WOW -- that wanted to have a separatist space. Men occasionally acted or had other roles at WOW, but the idea was a man couldn't be the lead creative person on a show. The man that's in the book who was important at WOW, Uzi Parnes, was a collaborator with Carmelita, but I think Carmelita would say his presence at WOW was often really contentious. So it was an open question -- and these questions are being asked before the questions of Who really is a woman? were as widespread as they are today.

Trans identity has entered the mainstream with startling alacrity.

One way maybe we should have expected it is that WOW was, unlike other spaces that started in the '80s, accepting of butch-femme identity; people were sort of pushing the envelope, so there was a playfulness. There were a lot of women who were thinking very consciously about gender and gender presentation. Being a butch lesbian's not the same thing as being trans, but...they're related. Personally, if somebody wants to call themselves a woman, I'm down with it [laughs].

With all the voluminous perks that entails.

A lot of us really had a learning curve around trans. I certainly did.

There's such a disparity in original members' lives since WOW; some are struggling, some have made a life that's very different from all-art-all-the-time, and some like [Fun Home's] Lisa Kron have achieved major success. Is there still a sense you all were in the trenches together?

I think Lisa early on wanted to not just be a big deal in women's theater, queer theater; she wanted to have an impact, and she imagined it could happen. Split Britches -- Lois and Peggy -- never had any thought that they were going to be on Broadway but would have wanted, and deserved, to take up the kind of space culturally, to be commissioned or have regular gigs where they didn't have to self-produce. I was able to support myself as an artist, but I didn't think I was going to be able to sustain it, and I was lucky enough to get a teaching job. I am grateful for my job, but I can't pretend that it isn't a loss for me, leaving New York: I'm living in a place where there's no local theater performance scene at all. I'm sure there's regret and some bad feeling about who got success and who didn't... Eileen Myles was never a member at WOW, but she did stuff there, and she has something in the book. She's someone in her 60s who's having the first touch of mainstream success -- not just getting a major publisher... That she would be referenced on a TV show, she would be on a TV show, she would be referenced in an indie movie... And she doesn't look like Rachel Maddow, like a butch with foundation; she's a genuine creature of the bohemian left. She had a tenured job in San Diego that she quit, which I think a lot of people including myself thought, Are you out of your mind? But she made it work.

How would you advise a group like WOW coming into being today?

I haven't lived full time in New York in 15 years, so I feel kind of at a loss to answer. A couple of the ideas that were part of the organizational genius of the place are worth thinking about, which are: 1) about having a space. It's true that real estate was cheaper in the early '80s; it's also true that nobody there had money. There was one trust-fund person, who wasn't willing to underwrite the whole thing, but the rest of us had jobs we depended on, and nobody had the kind of job to get a space. So figuring out a way to get a space together seems really worth investigating. And then finding different ways of being together. The art world mirrors the corporate world more now than it did then, even in just the language, talking about being entrepreneurial -- which of course we were, and you had to be -- but you thought about it in a different way. There were ways of structuring it that allowed maximum freedom, artistic expression, while still harnessing the power of the group and making people responsible for the space.

The thing that maybe is the most lacking in a more expensive real estate market and just a different moment is: not all of the work at WOW was really interested in mainstream success. In part because a lot of us couldn't imagine that that would ever happen. It was unimaginable. But a lot of us also were of a generation that still had this idea of -- we wanted to shift the culture in our direction, some sort of idea of a counterculture, or that the center would move towards us. But also a lot of people had a feminist ideal of not total separatism but I don't give a fuck about that. It's so important and so vital to make my work that I really don't care about the markers of mainstream success. It's probably harder to not care about it [today]. When you see some people like Lisa, who came out of WOW, having mainstream success -- of course she worked her ass off for years, but I don't think it would have been possible for an earlier generation to make the kind of work that she's making and have [that success]. So...thinking in some ways of forming a community, thinking about what art needs -- which in part is the room to make mistakes -- which existed at WOW. Most of the stuff that happened there was a mistake. But there was an idea that if you kept working, your work would get better. And you didn't need to have a BFA or an MFA -- a lot of people didn't have a college degree. You didn't have to show an artistic pedigree to get your foot in the door, and now that feels like maybe you do.

What do you want people to take away from the book?

I hope that the work is of historical but not only historical interest, that some of it gets produced, and that people support the artists in the book. That people will evaluate WOW not just on the fact that there are people who achieved some sort of markers of success. It's not just an important place because somebody came out of there and won a Tony or got Guggenheims. People made art that mattered to them that was good.

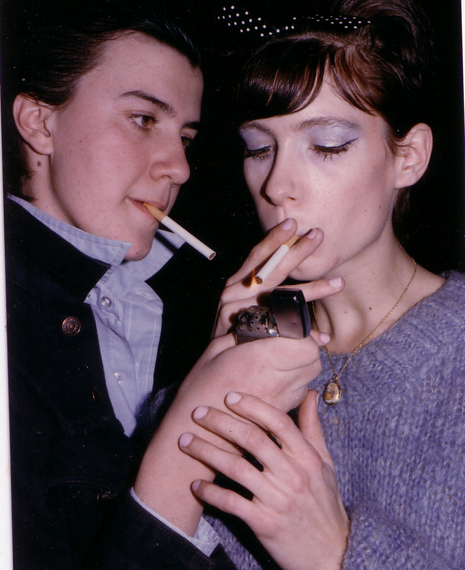

(DIANE TORR: PHOTO BY SASKIA SCHEFFER; UPWARDLY MOBILE HOME WITH SPLIT BRITCHES' LOIS WEAVER, PEGGY SHAW, AND DEB MARGOLIN: PHOTO BY EVA WEISS; SWASHBUCKLER'S MO ANGELOS LIGHTS UP LYNN HAYES: COLLECTION OF DEBRA MILLER; SHARON JANE SMITH EYES HELEN FRANKENTHALER IN THE WELL OF HORNINESS: PHOTO BY EVA WEISS)