The following is an excerpt from "One Big Happy Family" by Lisa Rogak:

“It’s not unusual for animals to be nurturing toward any species,” says John C. Wright, Ph.D., author of Ain’t Misbehavin’: The Groundbreaking Program For Happy, Well-Behaved Pets And Their People, and a Certified Applied Animal Behaviorist and professor of psychology at Mercer University. “The instinct to care for another animal can be hormonal, or simply related to age. If they’re young, their behavior is malleable, and they’re open to just about any experience, opportunity or companion. Like humans, animals, for the most part, yearn for company.”

For other animals, particularly birds, the drive to nurture and raise young is particularly acute, on both ends, for the parent and for child. At the same time, however, it’s deep within a newly-hatched bird’s genes to instantly glom onto the first thing it sees when it opens its eyes, whether that be animal, vegetable, or mineral.

Imprinting is a phenomenon among geese, turkeys and ducks that noted Austrian naturalist Konrad Lorenz studied and earmarked in the beginning of the 20th century. According to Lorenz, these birds are preprogrammed to consider the first large moving object they see in the first few critical hours and days after being hatched as their primary parent figure. Though you’ll discover that cats, dogs, and birds of other species can serve as the parental stand-in, Lorenz also found that newly-hatched birds can become attached to boots, balls, and in once instance, even electric trains.

“If you put an egg under a bird and if its instinct is strong enough it will go for it,” said Graham Appleton of the British Trust for Ornithology. “For the chick, anything that is there at the time becomes the mother and it will make all the right noises to try and get food. The parent’s instinct will be to feed the newborn.

“The little gosling’s instinct will be to follow the parent around and copy whatever they do,” he continued, describing one case where a peacock adopts a gosling. “This is certainly a strange situation and it may be a little confusing for the little bird. It will have some instinct of its own but it will be fascinating to see if it learns things like how to swim, which is something a peacock can’t do.”

Based on the real-world experience of zoologists and staffers at wildlife sanctuaries and other rehabilitation centres around the world, the number of interspecies parenting cases is bound to increase among animals – endangered or otherwise – in captivity. In the case of orangutans and other primates in captivity, at least, it’s a wonder there are not more instances of abandonment by new mothers. After all, given efforts to save endangered species and provide educational examples to the public, the living conditions for these animals are wildly different from the natural habitat they are accustomed to, so it naturally follows that their parenting styles and abilities would vary as well.

“Although we had endeavored to give our orangs the very best accommodation, we still could not reproduce the conditions they would have known in the wild,” said the late Molly Badham, a founder of Twycross Zoo in Leicestershire in Great Britain. “In their natural environment, the males live alone, only joining the females for mating, and orang females with infants often travel with other such females in a kind of nursery group,” an environment where the new mothers learn from more experienced veterans and come to know what to expect. In captivity, by contrast, males and females typically live together, which makes it possible for the number of births to be as frequent as once a year as the length of pregnancy mirrors that of a human.

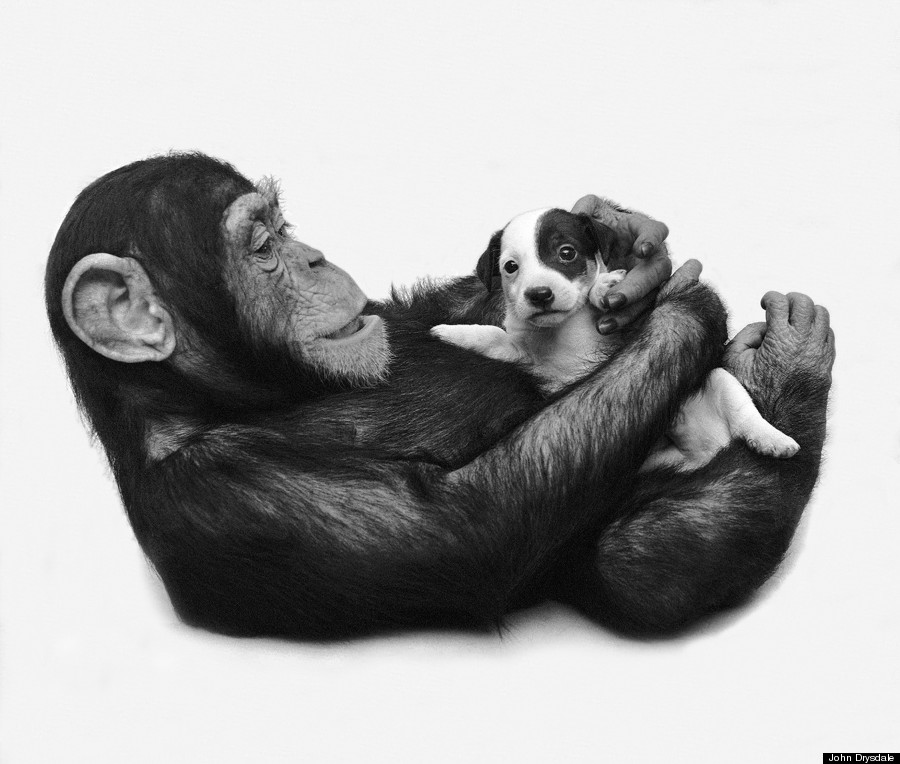

Happily, there’s a virtual abundance of other animals – particularly dogs – that are eager to step in and assume the role of nursemaid, teacher, babysitter, or merely assist their humans wherever they need help. Molly Badham, for one, preferred dogs, particularly Great Danes, to serve as surrogate mothers and fathers for the large numbers of chimps, orangutans, monkeys, and other primates that were often rejected by their mothers. “We found willing foster parents in our Great Danes, who were very tolerant of all the orphans who invaded their territory,” said Badham. “Perhaps it was because all of the dogs were rescued and this background might have given them an affinity to other animals that were in need of help,” she said.

In the pages of One Big Happy Family, you will read about some pretty incredible combinations, from a chicken caring for a litter of Rottweiler puppies to a pig helping to raise – and nurse – a kitten. But by far, the majority of stories involve a male or female dog acting as surrogate and foster parents. While some may wonder why this is so – perhaps it’s attributable to the fact that dogs are the most common household pet – the truth is more prosaic: it comes down to breeding and millennia of training canines to serve as a human’s best friend as well as to perform a wide variety of jobs according to a specific breed.

“Dogs have been genetically modified by us to be extremely sociable and extremely accepting,” says Stanley Coren, Ph.D., professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia and author of numerous books about dogs, including The Intelligence of Dogs: A Guide to the Thoughts, Emotions, and Inner Lives of Our Canine Companions. “Generally speaking, the issue is something we call neotony, which simply refers to the fact that we have bred our dogs so that they are effectively puppies for their entire lives.”

Text and images courtesy of Lisa Rogak.