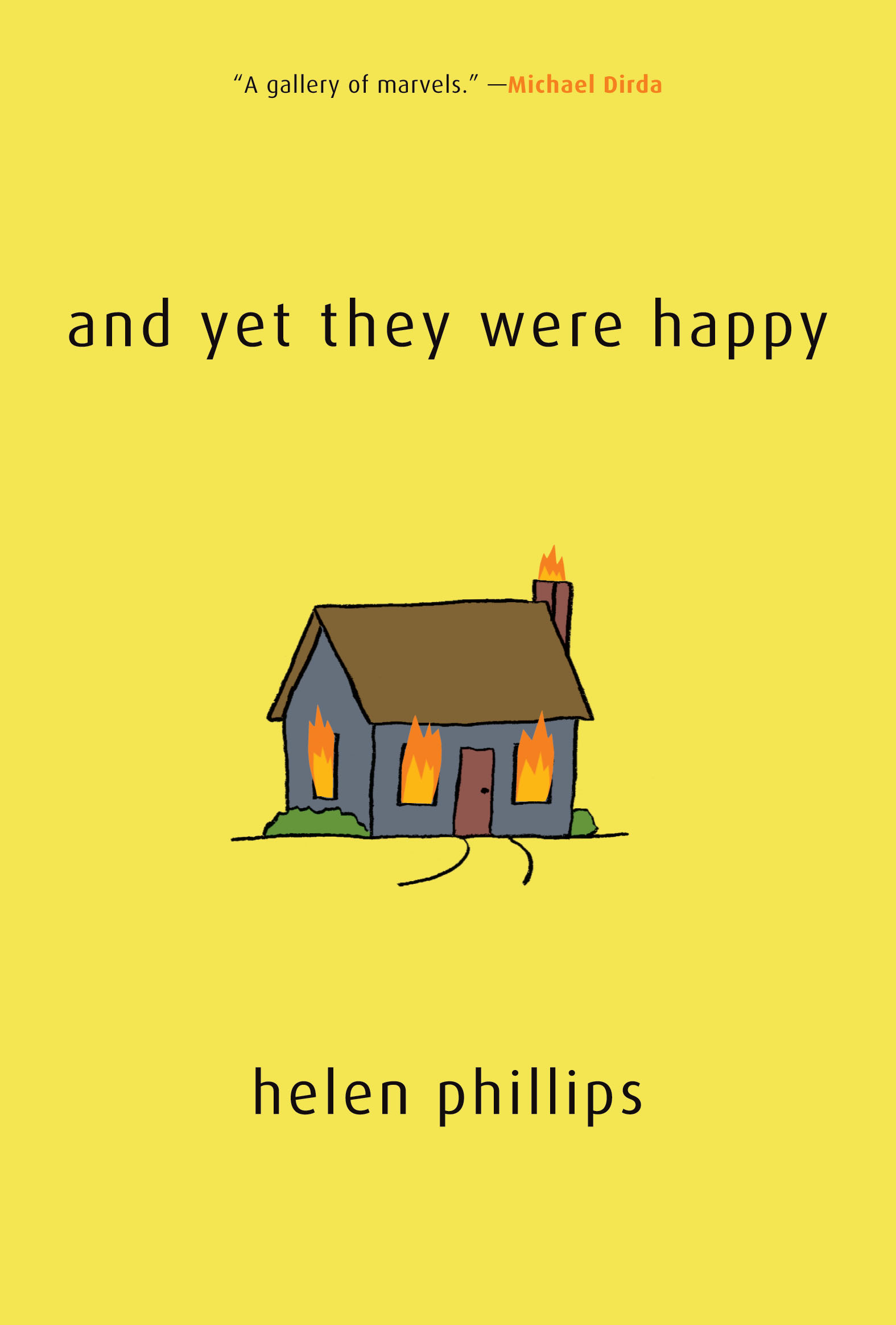

Hailed as a "brashly experimental debut" by ELLE and "full of gems" by Vanity Fair, Helen Phillips's imaginative book And Yet They Were Happy (Leapfrog Press, May 1, 2011) falls somewhere between novel, poetry, short story collection, autobiography and fantasy -- perhaps no surprise, coming from a recent winner of the Italo Calvino Prize in Fabulist Fiction. Phillips -- along with Rivka Galchen and ZZ Packer -- is the recipient of a prestigious Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer's Award. The linked fables of And Yet They Were Happy chronicle the adventures of a young couple setting out to build a life in a surreal, haunted world. Dazzlingly kaleidoscopic, it includes monsters, mermaids, Bob Dylan, Eve and a cast of other historical and mythological characters. We spoke about 340-word stories, independent presses and the refreshing qualities of apocalypse.

And Yet They Were Happy has an unusual format, consisting entirely of two-page stories. What was the genesis of this?

Some years ago I was feeling bogged down in the novel I was writing. The excitement of the original idea had faded in the long execution. I wanted to experience that initial thrill of creation on a more regular basis. Encouraged by my husband Adam Thompson, an artist who had recently given himself the challenge of doing all his work in pencil on 8½-by-11 paper in lieu of belaboring paintings, I set myself a similar task: I'd write one 340-word story every day. The idea and the execution became simultaneous.

Although the genesis of this book may sound rather formalist, in truth the constraint merely served as a sort of scaffolding that enabled me to explore central themes and concerns from many different angles. While it was helpful to have one thing to cling to amid all the chaos of creation, ultimately it's not so important. Its primary role was to set me free, to make me feel that, as long as I held to my little word limit, I could do absolutely anything, could draw any bizarre parallels, bringing together history and mythology and Snow White and Charlie Chaplin and my own experiences in one breath. I wrote this book while I was engaged and during my first year of marriage, which was an intense and transformational time for me. The idea of a book comprised entirely of 340-word stories might sound rather rigid; but this book is flesh and blood and mess and life.

These pieces are divided into sections with titles such as "The Floods," "The Weddings" and "The Regimes." How did you arrive at this structure?

The sections of the book were created fairly late in the process, after I'd written all the pieces. But because I'd found myself continually (obsessively!) returning to explore repeated themes (marriage, mistakes, family, natural disasters, supernatural visitors, punishment, apocalypse), it wasn't too hard to name and craft the sections of the book. I think of the fables in each section as various manifestations of the same experience. Here's the wedding ceremony where the bride and groom drive their guests away by laughing too much; here's the wedding ceremony that's performed by wooly mammoths. Ultimately these are a series of metaphors, many attempts to describe those milestone experiences that evade description.

The name "Helen" recurs throughout the book, and there's an entire section entitled "The Helens." How would you describe the intersection of the personal and the fictional in this book?

I'm definitely walking a line here between fiction and nonfiction, mythology and memoir. That said, many of the Helens who appear in the book are having fantastical rather than factual experiences: being held in a cage at the zoo, for instance, or working in the factory where virgins are made. I write to reduce the distance between my own mind and other minds, to reduce that essential loneliness of being isolated in one's own consciousness, in the hope that a reader will say, "Oh, yes, I too have felt just like a woman in a cage at the zoo!" So any use of the name or character Helen is not for egomaniacal purposes but rather to try to present myself as a living breathing human being on the page in search of metaphors that will enable me to express those inexpressible inner perceptions. Because my own experiences are woven in here, I do feel somewhat vulnerable, my various struggles on display in a pretty raw and honest way. That said, I hope the emotional urgency that powered this book will come through to the reader.

How did you find a publisher?

When my agent sent And Yet They Were Happy out to all the major New York publishing houses, they expressed concern about marketing a book that didn't fit into a clear genre, so I started sending it out on my own to independent publishers, including Leapfrog Press. I cannot speak highly enough of Lisa Graziano of Leapfrog; I'm very fortunate that my debut book found such a supportive home.

There's a section of the book entitled "The Apocalypses," and the theme of apocalypse runs throughout. Why are you so obsessed with apocalypse?

I think there's a tendency for the human imagination to head toward the worst possible scenario. And Yet They Were Happy is definitely an expression of my anxiety and paranoia about the state of our planet, politically, environmentally, cosmically. At the same time, there's something refreshing about indulging your imagination as it travels to that bleakest place -- by confronting the idea of the end of life as we know it and trying to envision what might come next, you take some of the wind out of your terror's sails.