Leigh Newman is the author of the memoir Still Points North: One Alaskan Childhood, One Grown-up World, One Long Journey Home (The Dial Press, Mar. 19). Also the books editor for Oprah.com, Newman writes beautifully and vividly about growing up as a child of divorced parents--shuttling between fishing and floatplanes with her father in Alaska and a less rugged life with her mother in Baltimore--and its effects on her adult relationships. I spoke with Newman about her Alaskan upbringing, how she recalled her adolescence so lucidly, and her massive collection of flashcards.

Your childhood in Alaska made you self-sufficient in a number of ways--often having to do with survival skills. Obviously, people become who they are for a multitude of reasons, but do you think becoming so independent was a big factor in your fear of attaching yourself to others as you grew older?

One of the things I most enjoyed from childhood was my parents' expectation--and most Alaskan parents' expectation--that kids pitch in. Usually, they showed me how to do something (once), but after that I was expected to stack the firewood, make the fire, pack the shotgun shell, gut the fish, pump the water out of the floats and so on by myself. When I was 8, my dad handed me the controls of our floatplane so he could take a "nap." This happened more than few times. He was joking (he wouldn't really fall asleep) but he was also testing me to see if I knew what to do in the air if something happened to him.

As a child, once you've gotten over your injured sense of being forced to work for no pay or praise, enduring those lonely minutes in the cold, dark garage when you (ridiculously) think you're the only kid in the world who has ever had to pluck a duck or wax a ski--you do learn to enjoy these tasks and the fancy, smug, adult feeling they give you. You're earning your place. This is what I think of as self-reliance, which is probably the single most Alaskan quality, one built into the state politics and culture and character. (This doesn't mean that other people won't help you out up there; get your car stuck in a drift and about 17 people will pull over to help push.) So in my case this independence was pretty much braided into my DNA and I'm exceptionally thankful for it.

However, as I grew older, that self-reliance began to morph into a kind of self-imposed exile. Relying on myself somehow became not trusting other people or fearing other people or being afraid that I was not good or not pure enough or not lovable enough to be with other people. And that flawed logic, that step from "doing a job yourself" to "doing life yourself" probably developed in response to my family situation.

My parents divorced when I was seven, and my mom left the state for her hometown of Baltimore, Maryland. They had joint custody, which meant I lived between Alaska and Baltimore, visiting either parent every four months. The flight took about 12 hours and 5,000 miles.

When I was with one parent, we didn't talk about the other. I didn't even think about the other. And I never, ever brought up problems in my own life at either house, ever--not problems at school, not problems with friends. I think this is not uncommon among the radically divorced kids of the late '70s and early '80s. You're afraid if you do something wrong, you'll be tossed out like the missing parent. I hate to say these things, because I love my parents. They didn't realize all this was going on under the surface. How could they have? I wasn't talking. I didn't even allow hieroglyphics of these thoughts to skitter across my brain. But the primary thought for me as an adult became: don't let anybody get in there. If they get in there, they're going to have power over you and leave you and you'll be sitting on a bench somewhere, swinging your legs, whistling, hoping nobody can see the panic and desperation.

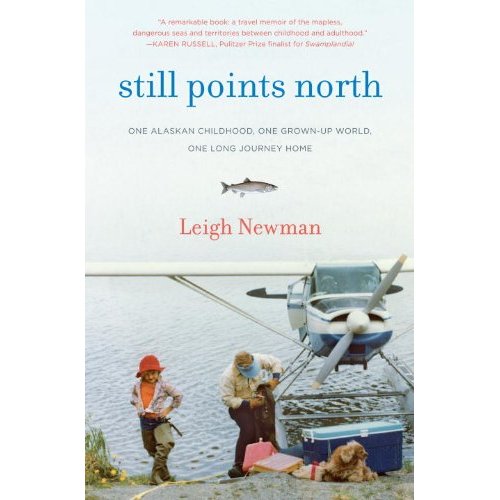

Photo courtesy of the author

Photo courtesy of the author

You very deftly slid into your childhood head in the sections dealing with your youth, writing in a style that doesn't condescend to childishness but seems to be of a child's point of view nonetheless. What were your strategies in writing these sections? And how did you remember so much of your youth?

I remember almost everything from childhood. Wherever I am -- a playground, a slow-moving meeting, an airplane ride -- as long as no one's expecting much from me, I'll shut my eyes and roll the tape for hours. (In fact, I probably don't even shut my eyes most times. I do it all the time driving, which is just another reason NOT to get in a car with me).

Daydreaming to me is another word for reliving age 2 to age 12. I'm not sure why the tape cuts off there. I've forgotten most of my adolescence, which is probably a good thing, and a good hunk of college. But those early years are just very vivid and concrete, down to the cringe-worthy details like picking already-chewed bubble gum off the ground and, yes, eating it... and the heavy, soul-plunking feeling that "I shouldn't tell my cousin I'm doing this because he'll tell somebody to take the gum away from me." The richness of shame! It's one of those emotions you can always count on to show up in full glory.

As for a strategy, I didn't have anything specific in mind when in came to the voice. I was my voice. I just wrote every scene down as I'd felt it -- and by feel, I mean the physical senses of taste, touch, smell, as much as the feeling sense of the verb. All that was still very alive for me. When you grow up in the wilderness, that sense of the concrete world is so fresh in you. It never really goes away, and it translates very well into writing, into creating worlds.

You and your mother discuss what it would have been like had you grown up solely in Alaska instead of also in Baltimore. Can you guess what your life might have been like had you done so?

Baltimore provided me with wonderful, life-changing opportunities. For me, that city was the big town. I had never seen a brick building and I didn't know what lightning was (we didn't have thunderstorms in Alaska). I got a terrific education there, one that allowed me to move on to college and travel the world. If I had stayed in Alaska, some equally wonderful things would have happened. I would have been more involved in skiing and duck hunting. My dad and I did a lot of duck hunting when I was little and it's something we enjoy and still do. It's just that, now, living in New York and not practicing, I'm terrible. He goes hunting and I go shooting holes in the sky.

You're also the books editor at Oprah.com. How has your job influenced your writing?

When I started at Oprah.com, most of the book had already been written and a first rough scene of the book had appeared as an essay in Tin House. What was left to do was a lot of huge, ugly, much-needed cuts, lots of rewriting, sobbing, and more rewriting.

With a full-time job, I'd now get up at 4 or 5 in the morning and do the book work before going to the office, a regimen I still follow. Getting up at dawn to do something ends a lot of inner dialogue and doubt. I have two young kids and a full-time job. I just can't afford to get up in the dark and fritter away my only free time looking a black screen or thinking about what I could do or having some kind of dialogue with myself about my abilities. A full-time job makes everything clear to you, including how serious and committed you. It's a litmus test of grit.

As for the nature of the job, I do cover books, but I also work with all kinds of writers on articles and essays, everybody from Jeffery Eugenides to Ann Patchett to Jim Shepard to Eckhart Tolle. I'm always reading and learning and listening and watching. I read about three to five books a week. I love seeing how different writers handle different challenges such as moving through time or contracting and expanding it. And it's hypnotizing to me how different writers use the same words so differently. (I have a monster flashcard collection, which frequently scares people when they see it, made of several thousand words -- one word per card, all of its definitions and roots, plus sample sentences where I've seen the word used in an unexpected or particularly elegant way)

But the most important influence to me has been the staff. When I walked into Oprah.com, I was a very different person. I'd spent the past six years writing alone in a room and raising my kids. I hadn't had a full-time job since the birth of my son. (I didn't even own office clothes. I had to borrow outfits from a friend.) My confidence was not exactly at its zenith. But everybody at the office cheered me on from day one, in terms of writing and putting that writing out in the world -- instead of, say, scribbling it down and the shoving it under the pillow. I was quickly given a lot of freedom to toy around with different articles and projects, and that confidence spilled over into the final drafts of Still Points North. This kind of support makes all the difference to a writer.