Gershon Shofman (Russia, 1889 - Israel, 1972) was one of the most prominent Hebrew writers of his generation. He wrote prose and poetry, he was a critic, translator, editor. Sarcastic humor is part of his non-sentimental, direct style of writing. He described daily events in a poetic and concise way. Shofman valued beauty and power. He wrote many very short stories, often with a basic plot that would end in a climactic way and used symbols and motifs that would point to a moral.

Shofman arrived in Israel in 1938, and he published his story "The White-Washer," a very short story of about 200 words, in 1942. The first-person illustrative story opens with the narrator telling us how anxious he was each time he walked near the house of his neighbor in the suburb, as the neighbor had hung himself in his basement. "It happened few days ago, and at that time the curious neighbors crowded around the sounds of the wife and the children shouting." Afterwards, the poor family moved out of the apartment.

On the day the narrator tells us the story, he sighs a sigh of relief because he sees the white-washer through the apartment's opened windows. The white-washer stands on his ladder while he neatens up the apartment. The narrator can hear the white-washer singing and whistling softly while working. The vacant apartment carries the sounds of singing and whistling with a far-reaching echo. "What tranquility in this singing-whistling, what indifference to all the tragedies in the world!" says the narrator with admiration. The worker was not using paint; he used whitewash, which is cheap and thin.

Now the narrator slows down his story and asserts by a succinct, mini "essay" his general observation about life. "Many bad troubles are in the home, in ALL the homes." He names a few predicaments and worries: illnesses, surgeries, pain of raising children, family matters, hurdles, suicides, frictions, separations and more. The narrator presents one trouble with brief details: "D i p h t h e r i a. The sleepless parents rush every morning to the hospital, where they are allowed to see their sick child only from outside, through the high windows; sparrows on the windowsill..."

The residents of any apartment live there until they vacate it after one trouble or another, removing its gloomy, somber furniture; then the white-washer scrapes away at the plaster, along with the troubles, off the walls, while he sings and whistles his soft songs. "What tranquility, what indifference towards all the tragedies in the world!" repeats the narrator.

At the end of the story, the narrator addresses his readers directly: "Go to the white-washer, you suffering people, to the white-washer with his ladder, listen to his singing-whistling in the empty, strongly echoing space -- and you will draw comfort and calm."

The narrator does not tell us in what country or time this happened, or what the religion of any of the characters was. The individual tragedy (suicide) is illustrative of various tragedies that can happen to anyone, anywhere, at any time. The crowd -- the neighbors who flocked to the yelling of the woman and the children -- gathered around because of curiosity only. Like other crowds in the work of Shofman, this crowd did not gather for a conscious cause. Repetition of some phrases and words, punctuation marks, words with bigger letters or spaced-out words highlight the main ideas. The heightened, moralistic ending is typical to many of Shofman's stories. He exposes the comfort and the security of home as temporary. Parents are helpless, fragile as a sparrow: a father commits suicide; the mother cannot sustain the family without him. In this work, Shofman mentions some of the tragedies that people face. In other of his works, various other conditions evoke trepidation, to name few: poverty, the complex legal system, the unknown, illnesses, being alone without love or help, aging and death, danger and war, harm to a son, war, the death of a close friend, fear living as a Jew. The narrator appreciates the white-washer because he can sing through the tragedies. Shofman harnessed this and made it a work of art.

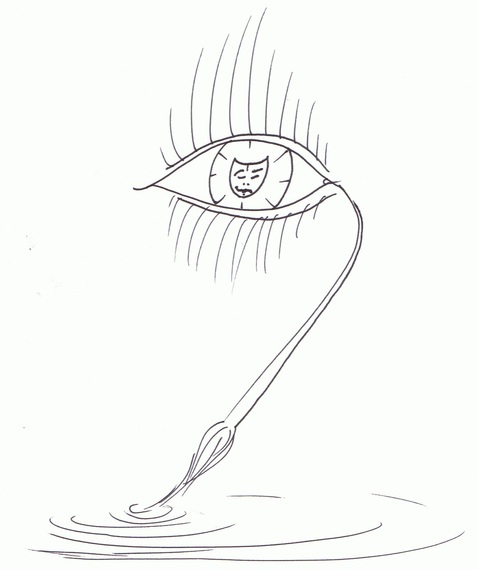

One may wonder if "whitewash" is our only comfort in tragic situations. Is apathy our only defense amid life's turbulence? Is all we can do when we face a disaster cover it up with a thin layer of an empty color? Should we accept that all of us sometimes face existential quandaries and all we can do in order to move on is to cover them with a whitewash? Should we accept helplessness and work on forgetting our tragedies by masking them?

The story may be sarcastic and darkly humorous, exposing the absence of true comfort in the world. There is often a contrast between the world and our heartfelt wants, but the present as is, is the only thing that is available for us. Is the whitewash of ignorance replacing faith in our challenging era? Isn't the world better with faith than without it, and do we have the faith to look at our circumstances as they are? Can we have the wisdom to take to the white-washer's song, without whitewashing? Can we use our song and the real paint of enlightened perspective to transform our space?