White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel and the international community seemed to breathe a huge sigh of relief on Tuesday after Hamid Karzai agreed to participate in a November 7th run-off election for the Presidency of Afghanistan.

For months, United Nation election monitors, diplomats and the Independent Election Commission of Afghanistan have disputed the legitimacy of the August vote (given widespread accounts of forged ballots, voter intimidation and "ghost" balloting locations that never opened yet magically reported votes).

But, after 3.1 million votes cast in the August election were deemed fraudulent, a Karzai concession to a run-off gets the ball rolling on mending the credibility of a country marred by violent political turbulence. This news is also valuable for the White House since this past week Mr. Emanuel strongly signaled the Administration's desire to work with a more "credible" partner.

However on Monday, before the announcement was even made, Defense Secretary Robert Gates underscored that the situation is an "evolving process" and will not change overnight "regardless" of what recourse is taken to resolve the tainted sense of their democratic process. Even this morning the officials preparing the new vote reported to the New York Times that fraud may not occur on the same scale as before, "but it cannot altogether be eliminated."

So while President Obama continues to deliberate over how best to engage with Afghanistan, and Rahm Emanuel publicly suggests that a clean electoral process is a necessary condition for continued engagement, the Administration's own Secretary of Defense claims that no drastic changes will necessarily stem from revisiting the elections, and top UN aide Kai Eide says they cannot stop fraud. With these seemingly crossed signals, one is left to wonder whether and how the runoff and its results will impact U.S strategy, resources and metrics for success in the region. Not only is it prudent to evaluate the different scenarios, it is also critical to underscore what guarantees America should place on the Afghani war effort regardless of outcomes.

If Karzai Wins

If the sitting President is able to extend his reign in Afghanistan, it will certainly help him recover some legitimacy in the eyes of his people and Western forces. However, it could also neutralize any perceived sense of change the Administration and Senator John Kerry (D-MA) -- a lead negotiator in the talks with Karzai -- hoped to drum up by announcing the runoff.

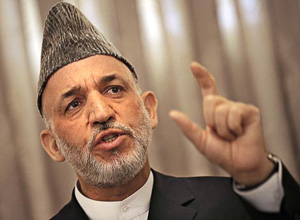

(Image Courtesy of Agence France-Presse)

(Image Courtesy of Agence France-Presse)

Regardless, the ability of the White House and Kerry, Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, to demonstrate a keen sense of diplomatic prowess with Karzai shined through this week. So, if Karzai were to hold onto his seat, the Obama Administration would be able to continue to exercise a diplomatic stronghold over him, paving the way for Karzai to be managed with "American tough love."

To those who spent months protesting the August elections, a Karzai victory will certainly paint the runoff as simply a cosmetic gesture brought to the Afghans by the very same system that disenfranchised their voice to begin with. Yet in this event, Obama ought to use that tough love to outline explicit conditions and demands for cleaning up corruption. Capitalizing on both the leverage that was displayed this week and Karzai's public outcry for more U.S troops, Obama could lean heavily on the Afghan government to act fast in cooperating with the training of the army and police forces, and establishing a more open civil society, by insisting resource allocation is contingent on it.

Of course Mr. Obama should be weary not to couch our brave men and women in uniform as bargaining chips. But, if open dialogue with whoever is at the helm of power in Kabul about what steps should be taken next and how our resources can best help, we can attempt to keep them more accountable.

This pressure cooker environment Obama ought to set up also offers an opportunity to address Karzai's ill-conceived practice of sometimes placing provincial governors in power that are not of the same ethnicity of those living in their district, which inevitably enrages populations pushing some further towards militancy. In order to cool the anger, the White House could tap into existing networks and alliances Karzai has established with the tribal elders in different regions, to gauge the type of regional reform locals desire. While this is another step towards nation-wide reform, this exercise can also allow Western forces listen to the regional mood and take the temperature on where allegiances lie -- an important litmus test in case there is an attempt to reconcile with more moderate Taliban members.

If Abdullah Abdullah Wins

The chief rival and former Foreign Minister to Karzai, Abdullah Abdullah, has welcomed the run-off with open arms and repeatedly asserted the need for change in his country beyond just cabinet-level personnel replacements. He has also stressed that as President he would strive to mend ties with Washington that continue to deteriorate given American frustration over corruption and Afghan frustration over civilian causalities from U.S missile strikes.

(Image Courtesy of the Associated Press)

(Image Courtesy of the Associated Press)

The anointment of power to a brand new administration in Afghanistan then, will likely force Obama's hand in boosting troops by at least a low-to-moderate amount (20,000 - 35,0000), since America will need to make good on its insistence that it would resource the country, once legitimacy is bestowed upon their election process.

Should he proceed with a troop boost, an Abdullah outcome could offer Obama cover from frustrated policy makers and constituents on the left. He will be able to frame the election results as a turning point in governmental legitimacy for the region that requires a renewed American spirit (and resources) to see through.

Even if Abdullah is elected as a change agent, however, the country will still be rife with vast networks of militants and tribal elders. In order to attain a balance of power, consensus amongst these regional groups and the central government will have to be built.

To that end, an Abdullah victory poses some shortcomings. 42% of the country is comprised of Pashtuns -- an ethnic population that makes up for a majority of top brass among the Taliban. As The Economist points out, "He may be half-Pushtun and half-Tajik, but as a prominent member of the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance, he is seen by Pushtuns as a Tajik, and by Pakistan as a stooge of India."

Pakistan helped the Afghan Taliban combat the Northern Alliance during the 1990s. So any residual baggage associated with these affiliations could curb Pakistani enthusiasm in "[combating] Taliban militants on both sides of the border." A sense of distrust among Pashtuns tribes towards the Northern Alliance would also compound difficulties for Abdullah in building regional consensus, as he would have to squander time alleviating fears that he did not represent an ascendancy of purely Tajik interests.

This demonstrates that Afghanistan is a matter more complex than just a consideration of the number of boots on the ground, but one that also hinges on parsing cultural differences. To address this, Obama must heed the advice of General Stanley McChrystal's strategic review and send out hordes of troops and civilian diplomats dedicated to immersing themselves in different regions to get a better sense of the local identity.

Moreover, Abdullah's anticipated inability to build bridges with differing factions underscores a larger need for President Obama to call for a recasting of the distribution of power in the country. By shifting more power to the parliament, and decentralizing authority to the provinces, away from Kabul, Western efforts could aid both Abdullah (and frankly Karzai) in equitably distributing power, a core tenet of the free and fair society Obama envisioned when he first unveiled an AfPak strategy in March of 2009.

Power Sharing

To this end, the Obama Administration has also signaled that it would welcome a power-sharing deal between the two contenders. While they are at odds over this notion, Mr. Obama adamantly expressed on Wednesday the need for key strategic decisions to be announced only after the November 7th election. This implies that (a) discussions with both figures are still fluid and (b) any reallocation of resources is contingent both upon the Karzai government's handling of the election and the behavior of both candidates.

In the event of some sort of political arrangement between the stubborn Karzai and the willing Abdullah, the White House can certainly expect to have to play a major role in midwife-ing an agreement. Thus, as our President ponders to what extent he wants to have a major stake in the country, a coalition government, while offering the supposed best of both worlds, both tacitly condones an illegitimate election and would require America to broker power among competing personalities and hash out new terms of a constitution.

Regardless...

When one teases out possible election outcomes and the ensuing plays the Obama Administration could make, it becomes painstakingly clear that no matter what happens, this is a tricky region where a myriad of complex variables come into play. For many, a November 7th vote is not just a runoff but a re-match of power structures and ideals. For others, it represents a culture of fear where 2 in 3 voters did not even voice their opinion at the polls in August due to coercive threats from Taliban militants and corrupt government cronies. Still, for others the re-vote represents nothing more than a cosmetic response to blatant fraud the first time around. As The Economist noted yesterday, "citizens are now deeply cynical about the scale of fraud, so many think it is not worth voting. Taliban violence during the first round underlined just how dangerous going to a polling-station can be. Nor will there be, as in the first round, provincial elections held on the same day to boost numbers."

(Image Courtesy of the Associated Press)

(Image Courtesy of the Associated Press)

Relevant to these outlooks, regardless of tribe or creed, is a sentiment among Afghanis that their lives are led in fear, in a hostile environment where the government does little to service the will of the people. That means independent of the outcomes and independent of the political stickiness for Obama, the United States cannot look the other way as a country withers at the hands of irresponsible leadership and hostile militants. Instead America must move to decentralize power away from Kabul, strike regional balances among provinces, strive to understand regional differences among factions and vie to build a civil society that affords its citizens the opportunity to live freely. Without this civic order, in a land where narcotics and weapons are trafficked, extremism will inevitably brew, fear will trump the rule of law and militants may open their doors to neighboring militants.

Finally as a tactical issue, Obama should be hesitant to reframe his war strategy as one that emphasizes battling Al Qaeda in Pakistan while downplaying the risk stemming from the Taliban in Afghanistan. Since September 11th, as Isobel Coleman of the Council on Foreign Relations states, "there hasn't been consensus within the Taliban on how to deal with Al Qaeda. The two have had a long and tumultuous relationship... It has never been a fly-by-night one and it won't be easy to simply divorce the two." Thus from a security standpoint it becomes America's prerogative to vigorously engage Taliban militants in Afghanistan (both to combat and reconcile with) in order to ensure that some with trace amounts of loyalty to Al Qaeda are rooted out and doors of safe-haven do not start reopening within Afghanistan. As Pakistan pursues its military offensive in South Waziristan, militants will certainly flood in and out of the porous tribal areas; clamping down on both Taliban and Al Qaeda militants with equal vigor is crucial for Obama to meet benchmarks of success in this region.

Thanks to Isobel Coleman of the Council on Foreign Relations, Brooke Lehman and Thomas Brugato for contributing insights to this article.