Next month my friend will bring her two kids to visit me in Brooklyn. It has become an annual tradition and I look forward to showing my young guests all that the borough has to offer. I'm not a parent but I am a Black woman who grew up in a white community, and so I understand my friend's concern for her African American children who have limited exposure to people of color and rarely get to see themselves as part of the majority. I send the kids multicultural books and activities throughout the year, and my friend keeps a vigilant eye on the curriculum at their progressive private school. But the self-esteem of these bright, beautiful children still gets bruised occasionally, and we both know that Black-authored books and a weekend in Brooklyn can't shield them from what lies ahead.

Like most New Yorkers, I'm a proficient jaywalker but when the kids come to visit, I try to change my ways. In western Massachusetts they've learned to wait patiently for the light to change, but here in Brooklyn we follow Moms Mabley's advice: "Damn the lights. Watch the cars. The lights ain't never killed nobody." Similar advice has been shared by generations of Black parents who reach a point when they feel the need to teach their children how to operate in a white supremacist society. Black parents often tell their kids that when it comes to dealing with members of the dominant group, "Listen to what they say, but more importantly, watch what they do." This is an important survival skill; blindly trusting the fine words of a powerful person can have serious consequences for someone who is already marginalized in society.

Most people would probably agree that integrity demands that all of us try not only to "talk the talk" but to "walk the walk." The recent #weneeddiversebooks social media campaign has raised awareness of the need for greater diversity in children's literature, and I am happy to see this important issue garner the attention it deserves. Activism around diversity isn't new, of course, but repeated calls for change over the past few decades have largely fallen on deaf ears. Those of us who have been advocating for greater diversity and equity in children's publishing are watching to see what will happen next. Will the overwhelmingly white publishing industry simply add a few more authors of color and call it a day? Will those who are new to the struggle be satisfied with superficial rather than structural change?

Missing from the diversity conversation is any mention of equity--equal opportunities for all. Right now the vast majority of children's books are written by white authors. If more of those white authors start to write about people of color (and/or LGBT people, people with disabilities, people from different socio-economic classes), that will increase diversity; more books for young readers will begin to reflect the range of different people in our society. But such a move would do nothing to ensure equity within the industry. Equity insists that everyone has an equal opportunity to participate and right now less than 5% of the books published annually in the US are written by African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans. As Debbie Reese recently pointed out on her blog, American Indians in Children's Literature, the identity of the author does matter:

Just about every book a kid picks up has white people in it. And, just about every book is written and illustrated by a white author or illustrator. For literally hundreds of years, white kids have seen themselves reflected in the books they read, and they've had the chance to see people who look like them as writers and illustrators of those books. By default, they've been able to see a possible-self. By default, they could imagine themselves as the writer or illustrator of that book. It may not have been a conscious thing, but it was the norm. The default. The air they breathe. Every day.

I want that for Native kids. I want them to see books written and illustrated by people who look like them. I want them to be able to think "Hmmm... I could be a writer, too, just like Cynthia Leitich Smith!" or "Hey! I could be an illustrator, too, just like S. D. Nelson!"

If you are a white author who wants to write about people of color, I would ask you to pair your concern for diversity with a comparable commitment to equity. Do members of the group you're writing about have an equal opportunity to tell their own stories? What can you do---in addition to carefully researching your story---to make sure cultural insiders have the same chance to be heard as cultural outsiders like you? When you plead for greater diversity are you only thinking about the person you see on the cover of a book, or are you also advocating for a wider range of people editing, marketing, and reviewing those books? If we don't change the structure of the industry, we can't expect different outcomes. It will continue to be business as usual.

Something else that's missing from the recent conversations about diversity is the bias against self-published books. If we all agree that the traditional publishing industry is not as inclusive as it needs to be, why then do we punish those writers who have sought out alternative ways to tell their stories? I am a self-published author; I have a PhD, an award-winning picture book (Bird), and two historical fantasy novels. But I also have 20 unpublished manuscripts and after a decade of rejection, I decided to publish some of those books independently. I confess that I did not hold up a placard, take a selfie, and post the photo online in early May. Instead I focused on readying the four "new" books that I have chosen to publish with CreateSpace this month.

I often get the impression that some advocates of greater diversity in children's literature think the dominance of white authors is some sort of unfortunate accident. Writers of color, the reasoning goes, don't get published because they aren't properly trained (send them off to get an MFA!) and therefore produce substandard work that (white) editors are duty-bound to reject. Others believe the claims of those same editors who insist they simply "can't find" the diverse writers they so desperately desire---despite the fact that they're operating in one of the world's most diverse cities.

In the twenty-first century we really can't afford that kind of naivete. It's no coincidence that the homogeneity of the publishing workforce matches the homogeneity of published authors. Writers of color are not being marginalized by accident. Their marginalization is the result of very deliberate decisions made by gatekeepers within the children's literature community. These decisions place insurmountable barriers along the path to publication for far too many talented writers of color. Some Black organizations recognize this reality: awards like the NAACP Image Award and QBR's Phillis Wheatley Award accept nominations of self-published books. I recently participated in a children's book fair at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum in Baltimore and several of the authors there were proudly displaying (and selling) their self-published books. Respected bloggers at The Pirate Tree and The Book Smugglers don't discriminate against self-published books and their reviews prove that indie authors can contribute a lot to the field of children's literature---if they're given a chance.

The industry will not change overnight---if it changes at all. If you are a bookseller, or reviewer, or you serve on an award committee and you have a policy that excludes self-published books, you are upholding the status quo. If you are a nonprofit that promotes literacy but you refuse to collaborate with self-published authors, you are supporting a system that disadvantages writers of color. If you are a librarian who wants a more diverse collection but you refuse to acquire self-published books, you are denying your patrons access to titles that might help to fill the "diversity gap." I'm not claiming that all self-published books are as good as those that are traditionally published (though let's admit that many of the latter are mediocre at best). I'm asking those who claim to want greater diversity in publishing to consider the ways in which their actions are closing rather than opening doors. Is it fair to blame writers of color who self-publish for failing at a game that's rigged?

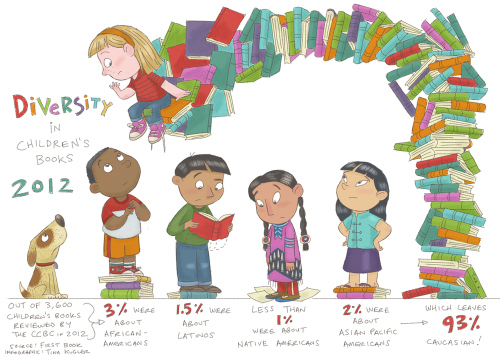

When I visit schools and share Tina Kugler's illustration with kids, they invariably react with shock and indignation. Children have a keen sense of what's fair and what's not, and they agree with my assertion that "Everyone has a story to tell." There is a large pool of talent in this country, yet the publishing industry is only giving certain individuals the opportunity to shine. As author Lyn Miller-Lachmann asserts on her blog, discrimination in publishing is no different than---and just as offensive as---discrimination in other sectors of society:

Our solution thus requires making common cause with those who are seeking to challenge other media stereotypes as well as those who confront other manifestations of racism in our society, such as mass incarceration, Stand Your Ground laws, restrictions on voting rights, health care disparities, and unequal education. Book people need to join with other civil rights activists and at the same time make clear that diversity in children's books is a civil rights issue as much as diversity in film, television -- and political participation.

We cannot settle for cosmetic change and we cannot allow ourselves to be seduced by empty promises. What we need is a commitment from publishers to take specific actions that will create lasting change---and we must hold them accountable. Hashtag activism and symbolic gestures have their place, but transforming the publishing industry will take sustained pressure; increasing diversity in children's literature will require support not only for inclusion but innovation. When writers develop different ways of sharing their stories, why not step out of your comfort zone, let go of the status quo, and give them a chance?