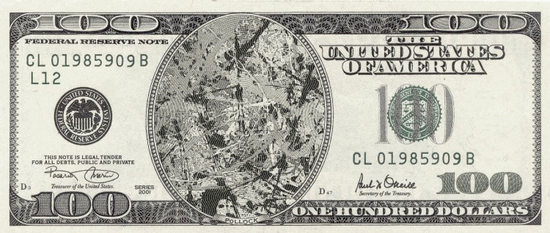

In Pollock We Trust: Digital collage by Photofunia.com

On November 12th of last year, Jackson Pollock's Number 16 sold for $32,645,000.00 at Christie's, New York. The 30¾ by 22¼ inch painting has a surface area of 684.1875 square inches, which means that it sold for $47,713.52 per square inch. To put this in context, the Median U.S. Household Income for 2012 was $51,017.00.

Just how did this Pollock painting -- a rectangle of paper covered with skeins of enamel paint -- come to be worth such a mind-boggling sum? It is a fantastic and vexing question isn't it?

I think there is a short answer and a long answer.

The short answer is that the figure of Jackson Pollock sits at the apex of a vast cultural construction: the currently accepted history of American art and culture. To explain how he got there, and how his work became a form of currency, requires a long answer.

Jackson Pollock (1912-1956), Number 16, 1949

Oil and enamel on paper mounted on masonite, 30¾ x 22¼ in.

© 2001 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jackson Pollock, who was born in 1912, perfectly embodies a cultural myth that has fascinated and obsessed Americans -- and those who have admired and/or envied American culture -- since World War 2: the myth of the heroic individual creator. Over time, Pollock's legendary status has been woven very completely into the fabric of a media society that has built art and culture into a very lucrative business.

Pollock is an artist who is seen as the prime mover and innovator behind a new American style of art (Abstract Expressionism) that blossomed in this county in the aftermath of our nation's defeat of the Axis powers. America's triumph in the war, infinitely aided by our having developed nuclear weapons first, validated our obsession with progress and paved the way for an era of American cultural hegemony that has lingered strikingly. Interestingly, if the rise of Fascism hadn't driven a generation of intellectuals to emigrate to the U.S. the nuclear bomb and Abstract Expressionism would have likely both been invented in Europe.

If the idea that Europeans would have invented Abstract Expressionism seems improbable to you, take a look at Joan Miro's 1925 painting "The Birth of the World," which features a background of flung and poured paint that the artist himself characterized as "free and unconscious." This work was painted eleven years before the American critic Harold Rosenberg published an article in the New Yorker describing the emergence of what he called "Action Painting."

Jackson Pollock led the American avant-garde -- originally a military term -- in its defeat and supersession of European culture. As we now know, Abstract Expressionism even had some CIA help in terms of becoming the representative style of American individualism and in turn confirming American exceptionalism. A new generation of critics, especially Harold Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg, made striking arguments for Pollock that helped him earn a lofty position in postwar America's rapidly evolving cultural Pantheon.

Before the war America's cultural superstructure already had been developing rapidly. The Museum of Modern Art was founded in 1929: the same year that seventeen year old Jackson Pollock moved to New York to study art. The growth of Pollock's career and the growth of the market for his work has coincided with the ascent of New York's status as America's -- and arguably the world's -- capital city of art and culture.

According to this informative chart -- A History of New York's Gallery Districts -- there were 140 art galleries in New York when Pollock arrived. There are now about 1500. New York's art museums welcomed some sixteen million visitors in 2012. Arts in the broader sense -- Visual Art, Theater, Dance, etc -- are a huge economic force: a New York state survey of 2010 identified 53,085 arts-related businesses employing 335,683 people.

Getting back to Pollock, a striking aspect of his work is that it is abstract. To put it another way, it requires anyone who accepts and or "likes" it as art to accept what was once a radical premise: that ideas are more valuable than skill. In the American model, progress starts with ideas and if you have a great one you are going to own a factory (or today an internet startup) not work in one.

The Philistine modern art haters of the fifties who would look at a Pollock in a magazine and say "My kid could do that" missed the point that Pollock was a "genius" who had changed how things were done because he had a new idea of how to do things: he replaced the brushstroke with the drip. Ideas begin in the mind as abstractions, and if you don't "get" a Pollock there remains a possible taint: if you need or like images or realism maybe you have an excessively literal mind.

Pollock's career unfolded in an era when the development of mass media accelerated and multiplied the dissemination of new ideas and images in art. Pollock's career was certainly aided by the rise of mass media: a tremendous impact was made by the spread Life Magazine did on him in 1949, which posed the question: "Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?

In other words, he got in early on a trend that was just emerging. If you are a visual artist living and working now you can't help but be aware of the fact that if you come up with a great idea in the form of an image it will be infinitely multiplied by a tsunami of jpegs that will spread your fame and increase your reputation across the globe. Try googling "Jackson Pollock" and you will get over 18 million search results. Jackson Pollock, who has been the subject of a feature motion-picture, a Pulitzer Prize winning biography and innumerable magazine articles and museum exhibitions has had his myth multiplied by a media society, and it didn't hurt that he died young in a spectacular car crash.

Pollock's secure place as an embodiment of Americanism -- and as an internationally famous artist ---has translated into extraordinary cash values for his art. The price record is reportedly held by his No. 5 of 1948 which is believed to have sold for $140 million in 2006. Disputes over the authenticity of several purported Pollock works have made for some very entertaining news stories in the past decade. Recently, the authenticity of what some believe is Pollock's final painting has come to hinge on forensic analysis of a polar bear hair found embedded in the paint.

It is an accepted fact now that works of art can serve as financial instruments just like stocks, bonds or precious metals. If you want to check the value of Jackson Pollock as a "stock" you can use the Mei Moses® Fine Art Index to get an objective handle on the market. Art databases including those at Artnet.com and AskArt.com have made access to data about the prices of art at auction instantly available to anyone interested in investing works of art. By the way, we still refer to people that purchase multi-million dollar works of art as "collectors" but is there anyone with that kind of money who shouldn't be called an investor?

One way to look at the prices for Pollock's work is to call it a great American success story. Can't we just sit back and beam with pride over the story of a troubled young man whose artistic legacy is valued by museums, auction houses and banking institutions? Another way to look at the situation would be to speculate that Pollock's prices are the result of a cultural asset bubble. What would happen, for example, if art historians came to a new conclusion and decided that Pollock was actually a rather minor artist after all? Books would need to be re-written, curricula redesigned, and museums might put his works into storage.

Pollock's Number 16 is an abstraction backed by an abstraction: the construct of America's cultural and artistic history. Like a one hundred dollar bill it is ultimately just a piece of paper that we have learned to trust as valuable. It is worth many millions of dollars only because an entire cultural system has been built on the assumption of its value. It seems like an unintended consequence, but the generations of predominantly left-leaning critics, curators, and academics who carefully constructed the story of American modernism ultimately built up a new asset class for super-wealthy investors.

It strikes me as ironic that an artist we value for his rebelliousness and innovation has now become a figure that is somehow beyond question. Could you get a job as a Museum Director in the United States if you told those interviewing you that you didn't care for Pollock? I doubt it. The process of turning Pollock into an icon and a commodity has gone so far that it is nearly impossible to turn back. Perhaps for that very reason, Pollock paintings continue to look good to investors. After all: Pollock is too big to fail.

Note: for another very illuminating take on some of the forces at work in the Art Market, have a look at the video below, created by Tymek Borowski and Pawet Sysiak.