Could modern Tokyo have a tree canopy covering 80% of the city? Could Tokyo's rivers and bay provide free clams, fish and seaweed to its residents? Why do we have trouble even imagining urban agriculture or economic growth in harmony with the natural environment?

These were all accomplishments of pre-industrial Edo Japan. Azby Brown's new book Just Enough: Lessons in Living Green from Traditional Japan (Kodansha International 2010) convincingly argues that the growing movement for sustainable living in the twenty-first century can learn from Edo's land and resource practices and its culture of restraint.

Just Enough writes against conventional narratives of progress and the still prevailing consensus that the newest technology will cure the collateral damage of industrialization and consumer society. Despite nuclear war, environmental degradation, and human-caused global warming, faith in technology as a magic bullet for what ails the Earth and human society persists. The Great Recession has provoked dueling experts predicting when consumer spending will rebound, but not a reconsideration of how we live in an increasingly connected world of finite resources.

The zero-emission automobile is just the latest dream of a magic bullet, or this decade's version of the fat-free potato chip. Just as industrialized food "products" did not cure the West's obesity problem, new automotive technology will not make suburban living and globalized consumption sustainable.

Recognizing that continuing down the same path will not produce different results, Just Enough argues that we Edo culture can inspire a desirable post-industrial future. Today's challenges faced by Japan and the world make the questions Brown asks all the more relevant. How did Edo Japan succeed in reversing forest depletion that threatened national collapse in 1600? What pre-industrial tools and regulations increased food production and distribution? How did Japan manage to more than double its population, including a thriving urban center, while preserving the environment?

Concerned with sustainable living, locavores advocate a reliance on local food and resources. Yet often we consider vital resources to be exclusively material. Brown contributes intellectually and practically by insisting that some of the most valuable local resources include cultural traditions.

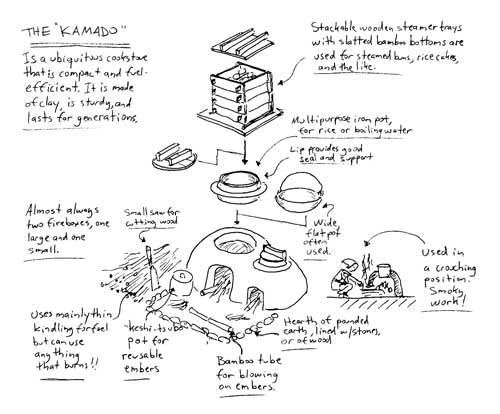

In his accessible and many-layered book, Brown immerses the reader in the lives of Edo farmers, city artisans and samurai by showing us their homes, neighborhoods, and daily instruments and activities. From rural to urban settings, we learn about domestic and public spaces, sustainable use of forests and rivers, food production and preparation, energy consumption, zero waste, and a dense metropolis whose quality of life rivaled or surpassed that of Europe in 1800.

Azby Brown is an architect, professor, author, expert on Japanese traditional and contemporary buildings, and director of the KIT Future Design Institute in Tokyo. In telling the story of Edo life and its lessons for today's quest for a new balance between human life and nature, Azby draws on all these skills and allows us to feel that we know about specific historical people, their families, and their social and ecological environments.

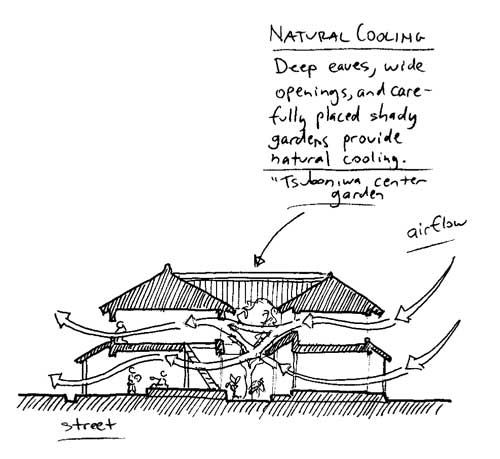

The book combines three levels of information to convey how life was lived in the Edo period: an introduction to a specific farmer, carpenter and samurai, with the context established as we approach their homes on foot; more than a hundred detailed drawings of forests, fields, neighborhoods, streets, waterways, houses, tools, and objects of everyday life; and finally dozens of ideas about what we can learn from Edo Japan.

Brown engages the reader with stories about people's lives, while explaining social structure, farming, transportation, forest management, urban planning, and domestic life. Myriad customs and regulations created a balance between forest, field and city. From building materials to clothes, the objects of everyday life combined function and beauty, with almost everything reused or composted. Success can be measured in the increase in national population from 12 to 30 million people, including over one million people living in Edo Tokyo, and the absence of many of the diseases that plagued European cities of that time.

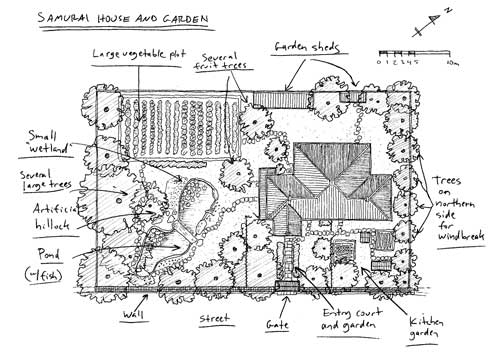

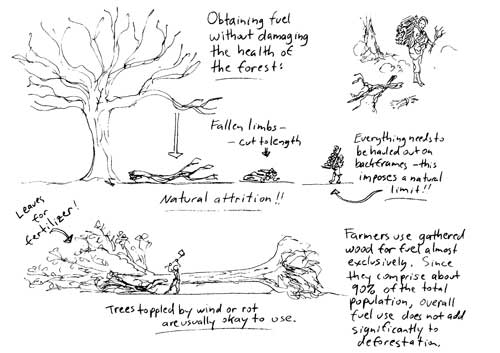

Brown provides a remarkable analysis of how natural resources were used by this growing population in a sustainable manner. Some notable examples include limiting forest extraction to fallen limbs and what could be carried on a person's back, an irrigation system in which channeled water was filtered and cleaned by rice fields, a transportation system that relied on human and water transport rather than animals, the role of courtyards as shared space for commoners, and samurais' reliance on household farming to make ends meet.

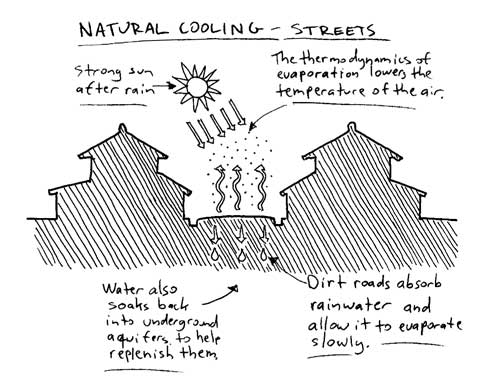

Viewed from today's perspective, it is remarkable to realize that Edo Tokyo benefited from an enormous tree canopy, permeable streets, and urban agriculture. Zero waste included re-using night soil as fertilizer, with a higher price paid for human waste from daimyo lords and entertainers because their diets were richest. By carefully showing how Edo people lived, Brown highlights architectural elements like the engawa porch that could be revived as a way of connecting interior and exterior, residents and visitors. Modular and multi-purpose rooms are other features that would again make domestic living more efficient and comfortable.

I wonder if Brown's focus on the Buddhist ethics of restraint will be easily understood or accepted by contemporary readers in Japan or abroad. I believe that pleasure and ecology must go together, so that making better choices is about improving life and not about "doing good." Appeals to doing good or preventing future calamity are less likely to motivate than persuading and demonstrating the immediate human benefits of cleaner air, livable streets, and nature's presence in daily life.

Likewise, we cannot turn back time or recreate the past in full. Brown does mention some of the coercive features of Edo life that would not be attractive today, such as strict class stratification and infanticide as a population control method. Clearly we must consider current values in choosing what Edo practices to reclaim for contemporary life.

To reverse potentially catastrophic environmental damage in our times, we need both inspiration and regulation. Individualism and consumerism offer certain pleasures, but so do shared resources and a connection with the natural world. The challenge is to inspire new urban practices, while also regulating harmful activities that were subsidized and encouraged by industrial society. We are only now realizing that free roads generate suburban sprawl, "cheap" food triggers public health crises, and fossil fuel dependence relies on endless international warfare.

Brown's book Just Enough is a compelling account of how Edo Japan confronted similar environmental problems and created solutions that connected farms and cities, people and nature. Like the phrase "urban satoyama," Brown's reconsideration of Edo life suggests that there may be specifically Japanese approaches to sustainable living, and that cultural heritage can play a prominent role in creating a better future. Some of these modern Edo ideas may be exportable to other countries. But perhaps this book will also inspire readers outside Japan to creatively search their own local cultures and histories for post-industrial opportunities.

Note: All illustrations created by Azby Brown for his book JJust Enough: Lessons in Living Green from Traditional Japan

Jared Braiterman PhD writes a blog about Tokyo Green Space, and his research has been published in magazines in Japan, Europe, China, and the United States.