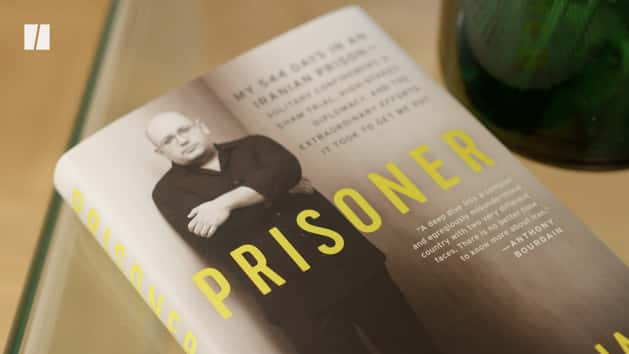

What does it mean to belong? For Jason Rezaian, the Washington Post reporter who was imprisoned in Iran for 544 days on spurious charges of espionage, that question is complicated. Rezaian, an Iranian-American, holds the record for longest imprisonment of a Western journalist by Iran. He explores this dichotomy of love for a country and shame for its actions — particularly after his arrest and imprisonment — in his new memoir, Prisoner.

He was born in the United States to an Iranian father and a white Midwestern mother. Like many kids in the Iranian diaspora, he became used to straddling two warring cultural identities, particularly growing up in the 1970s and ’80s. At the time, there was an increasingly fractious relationship between the U.S. and Iran — one that was exacerbated by the 1979 hostage crisis.

“I’ve always felt that you can be an American of any kind of background, and that’s going to be more or less supported by the American masses,” Rezaian told me. “I don’t think the same is true of a hyphenated Iranian. I think that the people of Iran that I encountered on a daily basis in all the years that I lived there accepted me as somehow Iranian … but somehow not.”

Prisoner is a harrowing, dark and surprisingly funny read. He and his wife, journalist Yeganeh Salehi, were arrested in 2014, not long after they appeared on Anthony Bourdain’s CNN show, “Parts Unknown.” Armed security agents of the Iranian regime collared Rezaian in the parking garage of his Tehran apartment and arrested him and Salehi. (In another revealing moment emphasizing a sense of placelessness, he admits that his Farsi wasn’t quite good enough to understand when his captor told him he was being arrested.)

Here, the couple’s stories diverge. Rezaian was transferred to the notorious Evin prison, separated from his wife. His imprisonment began with 49 days of solitary confinement, which he describes as a “living grave,” and after a closed-door trial, culminated several hundred days later in a dramatic U.S.-led diplomatic effort to release them.

The lingering sense of shame and love for the Iran he depicts — even after his imprisonment — resonated with me deeply. I’m British-Iranian, and living with that dual identity can frequently be uncomfortable, particularly when the Islamic Republic transgresses. In Prisoner, Rezaian tells a story that perfectly encapsulates this: His father, a rug salesman in San Francisco, gave a $1,000 rug to each of the freed U.S. Embassy hostages, with a certificate that essentially said, “As an American, I welcome you home — and as an Iranian, I’m so sorry for all that you endured in my home country.”

“I thought I had an opportunity to go there and tell a more nuanced story of this place.”

- Jason Rezaian

Rezaian’s desire to reflect the reality of people in Iran — away from the narrative about it presented by Western media and the Islamic Republic itself — was, he said, one of the motivating factors for moving there as a freelance reporter in the late 2000s.

“I thought I had an opportunity to go there and tell a more nuanced story of this place. It’s a massive country, 80 million people. And frankly, the Islamic Republic has done a better job of anybody at creating a negative image of its country and its people,” he said, referring to the “Death to America” rallies held regularly. “But I thought to myself, ‘If I can go there and I can spend some time there, I can tell a more complete picture.’”

Many Iranian-Americans like to point out that there’s a stark difference between the Iranian people and the Islamic Republic regime. When I asked Rezaian about the fact that the system is run by people (people who subjected him to psychological torture that he said made him feel he was being “broken down into a scared animal”), he was reflective. “I think that if you don’t believe that people are malleable and if you don’t believe that people can grow and can change and can be re-educated — or educated, in this case — then you would be much more inclined to believe that there’s no hope and we just have to do whatever we can to topple the current situation,” he said.

He has since filed a lawsuit against Iran for damages of $1 billion — a move he said he undertook in part to deter the country from imprisoning journalists and hostages again. Despite his treatment by the Iranian government, he is critical of the Trump administration’s dismantling of the nuclear deal and rejecting any move toward diplomatic rapprochement.

And unlike those murmuring of regime change, at various times floated by the likes of national security adviser John Bolton, Rezaian is adamant that Iran’s future should be determined by the Iranian people. “I like to believe that there’s always some hope. It’s what got me through a year and a half in prison and other difficult things in my life,” he said. “I was somebody who often, for a long time, promoted the notion of people-to-people contact between Iran and the United States. I still promote that. But I can’t advise people to go to Iran anymore.”