The QRF team is composed of 12 Marines and a medic. It is on call at all times. Its members don't shower and when they sleep, they sleep in their clothes. They are in continuous radio contact and when a call comes in, the goal is to be saddled up and ready to roll in less than three minutes. They are the firemen of the Marine Corps. Like firemen, when they roll it means the shit has hit the fan.

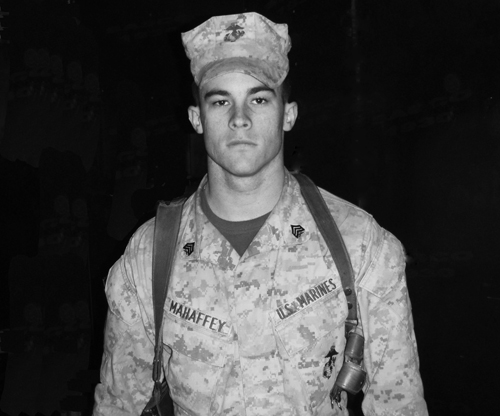

QRF is Marine-speak for Quick Reaction Force, and every base has one. MAP-3 is the call sign for Sergeant Jeff Mahaffey's squad (the Marines love acronyms almost as much as automatic weapons). Mahaffey's is one of several rotating QRF squads on the Combat Outpost (COP) at Haditha, in Anbar Province, western Iraq. Utah Trail is the dirt road leading out of the COP. When MAP-3 hits Utah Trail, in QRF mode, somebody is being attacked or overrun. You could say Mahaffey's boys are the modern-day cavalry.

All's been quiet on the western front for much of the current deployment of India Company (which started in Haditha, in August 2008). Until an anti-smuggling operation caught a group of oil pirates unawares in mid-December--which lead to a short firefight--the Marines at COP Haditha hadn't been fired on or fired on anybody else, in anger. Then things got kinetic in the third week of December. In Ramadi (the provincial capital) a demonstration/protest got ugly after the shoe-throwing incident in Baghdad--two Marines were injured.

And then, on the night of December 21, the QRF was activated for the first time this deployment. But Mahaffey's team (they are the mobile QRF, the guys who go wherever the action is) had to wait for another QRF team--one that normally pertains only to the COP--for backup.

"They got told 'There's Marines out there getting shot, MAP-3 is waiting for you at the gate, let's f---ing go,'" Mahaffey says, "and they get in the back of the trucks, like 'What's going on?' and then we're pumping down Utah Trail at 40 miles per hour. So it's like total fog of war. I give them props, they got there quick as f---. From the time the radio call came in, to the time I made link up with that squad leader, it was about 20 minutes."

"Com was so shitty," the Sergeant, continues, "all we heard was urgent casualty and taking fire. We went out there, linked up with Sergeant Hassell, got the casualty in the back of my second truck, got my other two trucks on line--facing the building they were taking fire from--and took a couple more rounds right at us. I was sitting there talking to some Lance Corporal about what happened--we don't get any information, you know, it's just to link up with the squad leader on site--and he's telling me 'This is what we've got, we're taking small arms fire from that building,' and all of a sudden, crack, crack, they start shooting again.

"So I gave my gunner an ad-rac [an idea of where fire's coming from] and told him 'Hey, frigging one o'clock, fire,' while we all got down on the berm and started shooting. Both my machine guns started. They put maybe 40 rounds apiece downrange. We put maybe 5 or 6 rounds at the corner where we saw the muzzle flash, called a cease fire, got everybody together, coordinated an attack on the building, and said 'Hey, we're going in, if that asshole's still in there, we're gonna take him alive.' I took two of my trucks up there and threw a p-frag in the building, but nobody was there."

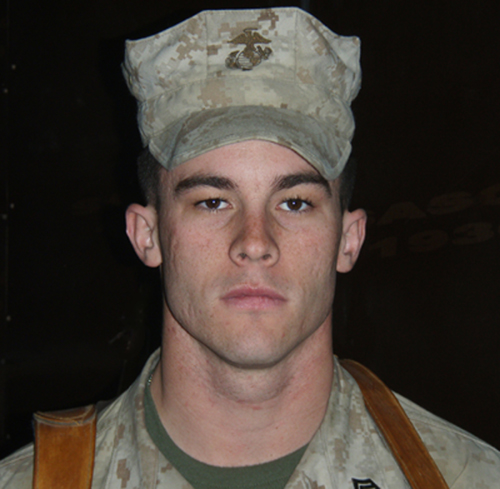

Mahaffey has been a Sergeant for a little more than a year. He carries himself with a cool and ageless confidence--one that suggests he was specially cut out for the type of work that men do in foreign lands. He's easy and well spoken in conversation, with a lively wit. He's also quick to laugh. His only regret stemming from the incident on the 21st is that his team didn't arrive a little bit sooner (the casualty was evacuated to Al Asad airbase and was only shot in the arm--he's expected to make a full recovery).

Sergeant Mahaffey is 22 years old.

A brown haired, brown-eyed product of the small town of Kewanee, Illinois (forty minutes south of Chicago), Mahaffey is a former high school wrestler--a 152-pounder at Kewanee High--and a self-described law enforcement type from a law enforcement family. As a kid he thought he was going to be a cop. Then, about the time he turned 16, the Marine Corps popped into his head. For a kid who spent his formative years running around the neighborhood playing war and pretending to shoot people--the Corps had a natural appeal.

He signed papers his junior year in high school, which caught the attention of his older brother, Jacob. Three years his elder, Jacob wasn't doing anything profound with his life and thought the Corps might be a good direction. The brothers ended up in boot camp together, in '04. Jacob went on to finish his college degree and is now an officer, pushing papers. Jeff, who has the aptitude for college, isn't interested in a commission. He likes the enlisted ranks and leading his men. He's already re-upped for another four-year term.

This is only his first deployment, a rarity in his battalion. After infantry school, Mahaffey went for special security training and was attached to a nuclear sub base in Kings Bay, Georgia. To his consternation, most of his buddies in the 3/7 went on to do two deployments in Iraq, while he was stuck doing guard duty in the South. But he earned rank quick and met Anne, who would become his wife in 2006. He says that while he never thought he'd be hitched at 21, marriage has been smooth.

His parents meanwhile--who divorced early in his teenage years--never expected him to be a Marine. When I ask how they feel about him being in Iraq, he says they're still adapting.

"They don't get enough of my Marine Corps life," he says. "My mom came when I was in Georgia, just to see how things were ... I've been in the Corps five years and I've picked up rank pretty quick, as far as my peer group goes, and my parents are still used to little old Jeff who was growing up in high school or junior high. I've excelled in the Corps, so I'm growing up a lot faster--they're having trouble catching up.

"My mom came to the pre-deployment farewell ceremony, where we all get our gear and wait in the parking lot for the buses to get there, and she's still used to the 16-year-old Jeff, her youngest, her baby son, and I'm running around doing shit, you know, I've got shit to do. We're coming from the armory and I gotta make sure my guy's got ... we're going to Iraq, you know, I've got to make sure my guys got their rifles, their frigging gear, everything f---ing thing I've got to do as a Sergeant. She just sat back with my wife and watched everything happen.

"I could see it in her face, she was like, 'I didn't even know ... you're in charge of people?' I was respectful about it, but I was like 'Yeah, I'm in charge of a few people.'"

We talk about the fact that a lot of American parents send their 18-year-old kids off to college and those kids come back at 22 or 23, basically the same dipshits--but with a piece of paper saying they've mastered a subject.

"I don't know if you're familiar with a fit-rep," Mahaffey says, "but it's pretty much a book report about how awesome you are at your job--or how much you suck; that's how you get graded as a Sergeant. I wrote my first one at the age of 21--I'd just picked up Sergeant. At the time, I'd conducted over 250 nuclear weapons convoys, I was in charge of 21 Marines and over $3-million worth of equipment--in my name, signed for every morning. I was signing for machine gun ammo, three machine guns, three Bearcat vehicles that cost a quarter-million dollars apiece ... that's my shit, I'm responsible for it.

"I wrote that on paper and I was reading it to myself to make sure there were no typos. I was like, 'F---, man, I'm 21 years old, I'm a senior Marine at this command and I'm responsible for 50-foot nuclear warheads being transported from the weapons wharf. I talk to my buddies back home and those guys are chillin' in the dorm room, smoking pot, drinking beer ... which I would love to be doing right now. I got nothing against that, because that's what makes them happy. If they're happy, I'm happy. And this is what I'm happy with."

Conversation turns to a notion I've heard from young Marines around Haditha since arriving in October--a yearning for the days of yore, a sense of nostalgia for the way the Corps "used to be." But the Marines still go to the same boot camp, right?, I'd ask. And they still carry a rifle and are expected to shoot people and get shot at? So what's so different about the Corps?

During a long conversation with another Sergeant, a 13-year vet, the topic of hazing comes to the fore. And then I remember those videos in the mid 90s, of Marine recruits being beaten and stabbed with pins and verbally berated. It was about that time anti-hazing rules went into effect--auspiciously analogous to the hazing policies established in national fraternities.

I'm told that when a Lance Corporal used to make Corporal, he'd walk a gauntlet--a dual line of Sergeants that would belt, punch and knee him in the legs. It was an age-old initiation rite and it would often leave new Corporals bed-ridden for a couple of days. It was outlawed with the new hazing policy. There was also the practice of pushing a Sergeant's new pin straight through his shirt, into flesh--and often into bone. These were Corps customs going back as long as anyone could remember.

The anti-hazing policy coincided with a general shift in U.S. culture--as the nation moved to become a kinder, gentler version of itself. Just as Marines can no longer haze, spanking a child has become suspect, and teachers can't use strong language with students. The idea of an educator striking a pupil is anathema, smoking isn't allowed in bars, and drinking and driving is verboten. Discrimination--even the hint of it--has become bête noir, the idea of separation of the sexes has largely been turned on its head, whistleblowers have their own hotlines and gays will soon be marrying legally. And yet, for all the newfound egalitarianism and understanding, the results are confusing: eight-year-olds standing trial for murder, soaring teen pregnancy rates, AIDS spikes in some populations, the sacred right of Roe v. Wade being invoked by Madonna to abort a baby because it conflicted with her touring schedule, and the mass media's fixation with the exploits of an under-educated backwoods floozy from Louisiana and a bevy of Hollywood drunks.

As the nation has gone kinder and gentler, society--in more than a few sectors--seems to have gone to hell. Many Marines complain that since corporal punishment was banished, discipline in the Corps has taken a similar turn. And, as Mahaffey points out, discipline is the backbone of a fighting force.

"It's like the other night," he says. "Lance Corporal Guzman, who's been in for a f---ing year, hears me yell, 'Guzman, twelve o'clock,' and he knows to fire. He doesn't think about it... Lance Corporal's don't get paid to think. That's my f---ing job. And I say, 'Guzman, twelve o'clock,' and he fires straight fucking ahead. I say, 'Guzman, three o'clock,' and he turns his turret around and fires at three o'clock.

"We build that relationship by him responding to me every time I tell him to do something. Every little thing in his life, he listens to what I say. And he respects me for it. And I don't abuse it. It's meant for Marines to not question themselves in combat, in my opinion. He didn't think twice about pulling that trigger the other night. Because I told him to, and he knows I have his back in anything he does. So Guzman didn't think, Well, should I fire? Where should I fire? Is the guy doing this? F--- it. He pulls he trigger and he does it well."

Mahaffey's talk bring back the words of an educator who once told me kids don't necessarily want easy teachers or ones they can be buddy-buddy with. They want consistency and a sense of discipline. If they know the rules, and the rules are fair, they will generally thrive. It's a notion that carries the conversation with Mahaffey to the 3/4 Marines--a unit that has, according to legend, been permanently barred from having its headquarters on American soil since surrendering in the Philippines in World War II (I suggest the notion is merely urban legend--which I'd read on the Internet--but Mahaffey assures me he has a friend in the affected unit, and their continued punishment is for real).

I remind him the Marine commander in the Philippines was facing overwhelming force and had the choice of throwing in the towel or watching his entire division annihilated.

"Which is Marine Corps policy," Mahaffey interjects. "You never f---ing surrender. So they say 'Good bitch, you wanna be stupid, go stand in the corner.' Fight to the death. Never ever ever will you see ... I don't give a shit if Map-3 is the only unit in a thousand f---ing miles. Our ass is gonna fight until that bitch is done. Until those Iraqis drive away in our vehicles, I'm not gonna stop shooting--know what I'm saying? That's Marine Corps wide, so 3/4 f---ed up, they got slapped on the wrist, and now they're part of Seventh Marines, 'cause they can't handle themselves."

In June, little Jeffy Mahaffey will celebrate the fifth anniversary of his graduation from high school. He will be up to his neck in training ops in the desert of California, preparing for 3/7's next deployment--Afghanistan, 2010. The prospect brings a twinkle to his eye.

"Yeah," he says, "Afghanistan's gonna be a good time."

For more observations from Iraq, go to http://sdliddick1.shutterfly.com/