Louis Lewandowski may be the greatest German composer you've never heard of. But hearing his setting of Psalm 150, just once, launched the career of America's leading conductor of Jewish music. And hearing his music, just once, launched a festival of his Jewish music... in Berlin.

Which means that from December 18 through 21, Berlin, of all places, will be alive with the sound of Jewish music, performed in two churches and two synagogues by Jewish choruses from all over the world.

All coming to Berlin on the dime, or the mark, or more accurately the Euro, of a Gentile businessman, Nils Petersen. He heard Lewandowski's music on a chance Friday night visit to a synagogue's all-Lewandowski service with a professional cantor, choir, and organ.

He fell so deeply in love with what he heard that he started the Lewandowski Festival.

Bringing Jews from around the world to Berlin, to sing.

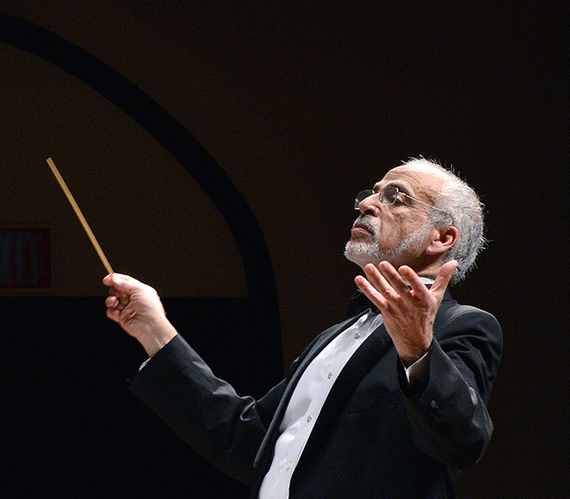

Josh Jacobson first heard Lewandowski as a 15-year-old at summer camp; he was so struck by the music that he found his life's work: conducting; studying; teaching; and performing Jewish choral music.

Jacobson founded Zamir Chorale of Boston, America's preeminent Jewish choir, which will be making its second Lewandowski Festival appearance in December.

"It's not about the Holocaust," Jacobson says. "It's about reviving the culture that existed in Berlin before the Holocaust."

Still, vestiges of the Holocaust haunt every footstep in Berlin.

"You can't put the history out of your mind," Jacobson says. "There's an eerie quality when you think about what happened in those same streets. You see brass plaques all over the city - 'Mr. Goldberg lived here and he died on Auschwitz, 9 September, 1942,' or whatever. It never lets you go."

Jacobson says that Germany, of all the countries of Europe, "is doing the most mea culpa/alcheit/atonement, if you want to use the word, for what they have done.

"Every German child must take a course on the Holocaust and must visit the death camps. Germany is also the most friendly toward Israel."

At the same time, Jacobson avers, there's much more to Berlin than Holocaust remembrance.

You can also see where the Berlin Wall stood," he says, "and you can go to the Brandenburg Gate -- there's so much history in Berlin. Yes, the Nazi era and the Holocaust are part of the city's past, but there's so much else. Here's where Napoleon marched in. Here is the home of great composers, great conductors -- it's a beautiful city."

"When you go to Berlin," he adds, "there's Golda Meir Street and a Ben Gurion Street. The double decker tour buses have Israeli flags. Clearly there's enough of an interest in Israelis and those who speak Hebrew to have that flag out there.

"Most of the audience at the Festival, like its founder, are non-Jews. They come because they love the music."

Lewandowski himself was an orphan from a small town in Poland who came to Germany and created a magnificent career for himself as a composer and a conductor.

Jacobson says that as a composer, Lewandowski "rates an A-, just below a Mendelssohn, a Wagner, or a Bach. And that's not bad!"

The Festival weekend is a whirl of rehearsals, concerts, synagogue services touring, and grand meals -- all prepared by a kosher caterer, at the finest locales in Berlin. One of the performances takes place at the Rykestrasse Synagogue, an old Reform Synagogue restored by the German government.

For Jacobson, the Festival is a spiritual homecoming, a celebration of the music that gave his life a direction he has followed to this day.

And yet, there is always the spectre of the Shoah.

"When we went on our first big European tour in 1999," Jacobson says, "we sang in Poland, and we visited some of the concentration camps. There were singers whose families had lost members in those camps. For them, it was very moving. You see certain buildings and you know how they were used during the war.

"You can see us singing at Auschwitz, people crying and hardly able to finish singing 'By The Rivers of Babylon.' In a sense, it's a kind of a victory, saying, 'We're back here. We're not extinguished. We're making sure that culture wasn't wiped out.'

"As a people, we have returned without shame."