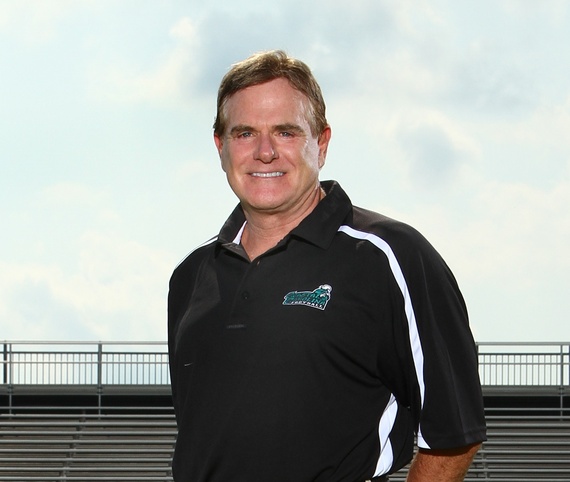

In the first of my two-part interview with Coastal Carolina head coach (and TD AMERITRADE chairman) Joe Moglia, we drilled into the details of Joe's Be a Man philosophy, which, according to him, is what lies at the heart of his success in business, on the football field and in life. Here's what BAM looks like in action.

In June of 2007, two hedge funds started acquiring TD AMERITRADE, amassing an 8.4 percent stake. The fund managers were publicly pressuring the company to merge with e*Trade and were highly critical of Moglia and the board for not being good suitors. Part of the board agreed with them. Moglia had a background in fixed income and was concerned about the risk in e*Trade's balance sheet. In the end, Joe prevailed and TD AMERITRADE just said "No," to the merger.

Four short months later, on October 17, 2007, e*Trade reported a net loss of $58 million, largely due to loan losses of $187 million. Meanwhile, TD AMERITRADE reported record net income on October 23, 2007 of $646 million. TD AMERITRADE's market value today is over $18 billion.

In my interview with Joe Moglia, I asked him about that deal, and how he managed to call it right and keep TD AMERITRADE profitable, when almost every major brokerage around him was drowning in bad loans during the Great Recession.

Natalie Pace: Let's talk about peer pressure -- something that can spawn bad behavior in college and on Wall Street. Going back to 2007 when you were still the CEO of TD AMERITRADE, and all of the brokerages around you were having fun, fun, fun making a killing in subprime mortgages, how did you have the prescience to steer clear?

Joe Moglia: I understood fixed income. I understood how the balance sheet works. I understood the inherent risk that you were taking by leveraging the way that Wall Street was leveraging. They were doing that because it enhanced their profitability and it gave them bigger bonuses. They weren't taking the best interest of their entire franchise at heart when those decisions were being made.

NP: Knowing you're right can be a lonely seat, when the rest of the world is going a different direction.

JM: Part of being a leader -- part of this BAM philosophy -- is that you have the courage to do the right thing, regardless of what might be expedient at that particular moment of time. TD AMERITRADE had six record years in a row. We outperformed every financial firm in the world over those 5-6 years. We were leading the industry in consolidation. We were doing very, very well. We were attacked, part of it was an internal attack, but most of it came from the outside. The activist community attacked us for not being aggressive with our balance sheet, and that we should be doing a deal with e*Trade. They were coming after us. Most of the time when activists come after you, the firm is weak. That wasn't the case with us. But they keep pounding your board. They keep coming after you.

NP: How did you gain the support of your team?

JM: We called an emergency meeting of everybody in New York. I said, "Our strategy is ABC. Do we want to change that strategy?" The answer was no, so it made sense for us not to do the deal with e*Trade because of the risk they were taking on their balance sheet. That was the summer of 2007. That October, e*Trade was one of the first firms to say, "By the way, I've got problems on my balance sheet." If we had done that deal, we would have been a $30-32 billion market cap company, and we would have dropped to $5 billion.

NP: Why did you give up the corner office for the fifty-yard line in 2009? You were riding pretty high on Wall Street.

JM: I just finished my 21st season of football. A lot of people may not be aware of that. I've just gone about it a little differently. Before I went to Wall Street, my career was coaching football. My last job was as the defensive coordinator at Dartmouth. After 16 years, I left coaching and I began in the Institutional MBA training program at Merrill Lynch. There were 26 of us. 25 MBAs and one football coach. The vast majority of the people who worked at Merrill Lynch just assumed that I would never make it there. I was fortunate enough that was not the way it turned out. So, then I left Merrill Lynch and I went to TD AMERITRADE.

NP: With TD AMERITRADE doing so well during the subprime crisis, while so many brokerages, including Merrill Lynch and e*Trade struggled to stay in business, your dance card had to be pretty full with career offers.

JM: When I stepped down, because we had gotten it right, I was probably in more demand than I've ever been in my entire career. In 2008, it was Armageddon on Wall Street. We had our sixth record year in a row. I thought the timing was right to pull the trigger on my own succession. So, we did. The board asked me if I would stay on as chairman, and I'm still chairman of the board at TD AMERITRADE. There was a lot of interest in bringing me back to New York. There was potential interest in me having my own TV show. And then I was contacted by a group of alumni associated with Yale telling me that at the end of the 2008 season, there was a chance that their head football job would be open, and would I be interested. I literally looked at the phone, almost incredulous, and I said, "You guys recognize that I haven't coached football for over 20 years!"

NP: Let's face it. The salary of a football coach is a rounding error compared to what you could earn as the CEO of a major brokerage. Why did you take the Yale offer seriously?

JM: Over the span of the next few months, I frankly found that I didn't lose a minute of sleep over the business and media opportunities. I couldn't get the football thing out of my head. I've always loved the strategy behind the game. But truly, having an impact on an 18-22 year old boy's life, helping the boy become a man, it's tough to find another field of endeavor that gives you greater satisfaction than that.

NP: It's one thing to have a desire to impact lives. It's another to have to downsize to pursue a passion. For a lot of people, they simply would say, "I can't afford that kind of choice."

JM: When you do a great job on Wall Street, you get paid a lot of money. I was fortunate enough that I didn't need to worry about money. So, that part of it never entered into it.

NP: Let's talk about when money was an issue for you. Why did you leave football to go to Wall Street? Who has the courage to be the only football coach (and rather mature at that) in a MBA training program?

JM: It was my first year as the defensive coordinator at Dartmouth. We had four kids. We were going through a divorce. I couldn't afford to live independently and support my wife and four children. So, I moved into a storage loft above the football office at Dartmouth. I didn't mind that so much, but it had no heat, and I could see my breath in the wintertime. Dartmouth is in New Hampshire. It gets cold there, and I lived there for two years. In January of 1984, Miami had upset Nebraska for the national championship. They had offered me a job. For me to go as the defensive coordinator at Dartmouth to a national championship team is an incredible next step in terms of my career! But the reality was that my kids were going to live in New Hampshire. I was going to live in Coral Gables. A football coach works seven days a week during the season. You do not get a day off for five months. Especially back then, we didn't make any money. I couldn't afford to fly my kids back and forth. I didn't have a day off where I could see them. I realized that I couldn't do my job as a coach, if I couldn't live up to my responsibility as a father. So, probably the toughest decision I've made over four decades, two in the world of football and two in the world of business, was turning down that job because it meant that I had to get out of coaching. So, I thought, "What else do I have an interest in, and potentially have the skillset to be passionate about?" And I always had an interest in Wall Street.

Click to read the first half of my interview with Joe Moglia, where we focus on his BAM (Be a Man) system.