Walking into John Himmelfarb's studio in Chicago is like walking into a candy store, a visual onslaught of colors and excitement, followed by a rush of desire to have everything at once. The subject of an upcoming documentary, his work is included in more than 40 museum collections. Normally you can tell the style of the artist by looking at a few of their paintings. But, the visual vocabularies Himmelfarb employs are so diverse, that it could have been the work of several artists, frenzied cousins even. I caught up with him at his studio to find out more about what drives him and his work.

Judy Chang: When did you come upon your unique style of painting?

John Himmelfarb: In 2003, during a visit to the Art Institute of Chicago, I came across a painting by DuBuffet, a favorite artist of mine since childhood. I don't remember the imagery, only the technique. It had a varied color background over which lay an image executed in a very liquid, thick, black line. I admired the simplicity and effectiveness. Then I went back to my studio, laid down a blue and green background, mixed a fluid black, and began drawing without preconceptions. A truck emerged. Without knowing why, I knew that this was a very important image for me. It has continued to develop over the past eight years.

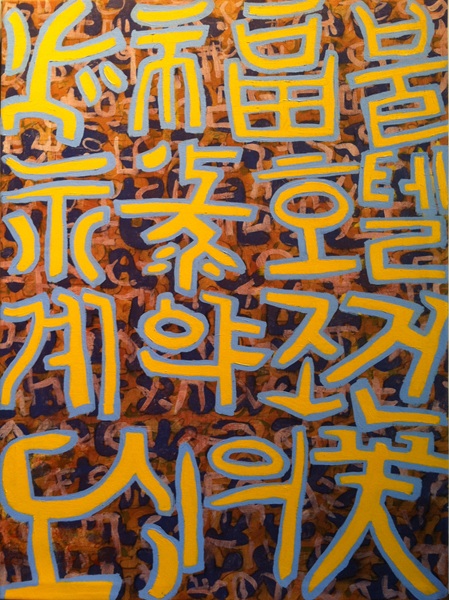

JC: What inspired you to make Poem of Prospero? What do the symbols mean and what does it represent to you?

JH: Since childhood, the way humans make marks in order to communicate with each other has fascinated me. Early memories to trips of Chinatown are predominately about the signage and the graphic qualities of the newspaper typography. Many of my own drawings since college days have looked like language: pictographic, hieroglyphic, calligraphic, etc.. (A show at Luise Ross Gallery in New York in 2007, Ideographic Sequence, examined this aspect of my work over a 30-year period. Jonathan Goodman covered this in Art In America.)

After traveling to Seoul for an exhibit of my work in 1996, my paintings referencing language changed to reflect the bold and regular quality of Korean commercial signage. Poem of Prospero is an example of such a painting.

JC: What do you think is unique about your process?

JH: I make lists of ideas and works I would like to make. But I rarely look at these lists after making them. They get lost in the creative chaos of my studio. I always have many more ideas of what to do than time to do them. I often ruminate about these for long periods of time and then, at some point, one of them ripens and calls to me urgently for execution. In January of 2010, I created a plywood sculpture I had thought about for some time. When I began, I forgot about everything else in my life and spent three very long days in my studio making Geared Up. When it was done, I immediately realized I wanted to make something in the same vein but much larger. A year went by, while I thought about this and waited for an opportunity to do this. In January of 2011, I drove a load of wood to a studio near Spring Green, WI. I have been renting this space for making large scale sculpture for the last few years. I allotted myself 10 days without interruption and was able to build (composing as I cut) the larger piece, The Road Ahead Leaves a trail Behind.

JC: What advice do you have for aspiring artists and what was the best advice you got from other artists?

JH: When art students ask me how to decide if they should pursue the life of an artist, I suggest that they follow any other direction they can find equally satisfying. Unless that choice is poetry, it is going to be less difficult and more remunerative. However, if someone knows that being a visual artist is the only thing that will make life worth living, he or she should have no fear. There are limitless ways to make this kind of life work, and there is freedom to invent a way of one's own. No rules.

John Himmelfarb was born in Chicago in 1956 and raised in a woodland setting 30 miles west of the city. He graduated from Harvard in 1968 and the Harvard Graduate School of Education in 1970, then settled in Chicago where he has worked since. Since being included in his first national exhibition in 1967, Himmelfarb has exhibited widely throughout the U.S. and abroad. He has received awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Illinois Arts Council, and the Pollack Krasner Foundation. Represented in New York since the 1970s, he currently exhibits regularly with the Luise Ross Gallery in New York, where another exhibit is scheduled or 2012. A show at the Cultural Center of Chicago ran from July through September 2011. Two museum exhibitions are currently scheduled, one in 2013 and the other in 2014. His website is here.