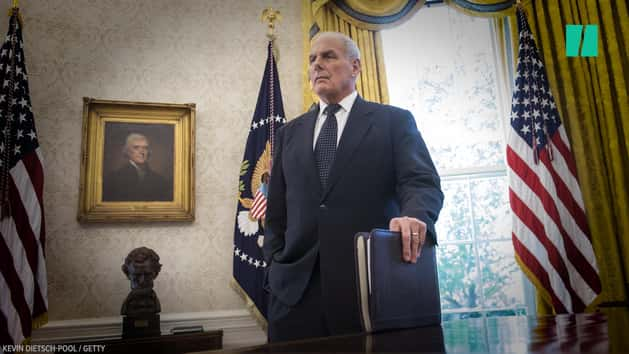

The White House chief of staff needs a history lesson. Yesterday, on Fox News, John Kelly claimed that a “lack of ability to compromise” led to the American Civil War. Free states and the federal government had, in fact, been compromising on the issue of slavery essentially since the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Kelly’s words are revolting on two levels: firstly, and obviously, Kelly is chiding the country on its inability to compromise on the ownership and exploitation of another human being. This is unprecedented for the chief of staff of a sitting president. Secondly, however, is the danger inherent in his revisionist, ahistorical comprehension of the Civil War.

There has always been a concerted effort to shroud the Civil War in layers of unnecessary complexity, explanations I hear often in the South. Breaking the war, and its incitement, down to its most naked truths is not liberal revisionism; it’s not, as Kelly claimed, “scrubbing history” to remove monuments celebrating men who took up arms against the United States in defense of the ownership and torturous treatment of innocent men, women, and children. Scrubbing history is saying exactly what Kelly did yesterday.

The compromises that the government had been continuously striking in its attempts to deal peacefully with opposing views towards slavery became untenable during Westward Progression, a term that is unlikely to ring many bells in the chief of staff’s head. For decades, the United States had maintained a tenuous but equal balance of senators hailing from both slave-owning and free states. In the early 1800s, the territory of Missouri was preparing to enter Congress as a slave-owning state, upsetting the delicate balance that had been in place. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 allowed Missouri to enter as a slave-owning state and, as an equalizer, the free state of Maine entered as well. Another key provision of the Missouri Compromise was the promise that all states north of the Louisiana Purchase territory would remain free.

The balance of free states versus slave-owning states was upset again in 1849 when California, which had long shown free state-leaning tendencies, requested to join the United States. The southern states were circumspect, aware that the balance would again be unsettled. The result? Another compromise, this time called the Compromise of 1850. Meant to ensure that the interests of all parties remained intact, California was permitted to enter as a free state with the promise that slavery would end in Washington, D.C. The compromise also dictated that ‘popular sovereignty’ could answer the question of whether or not slavery would be permitted in the Utah and New Mexico territories. This was somewhat palatable to the North. What was unacceptable was the new ruling that Northerners were now obligated to assist in the re-capture of escaped slaves who had successfully fled to the North ― a rule that directly violated state laws. And yet, the young nation kept attempting compromise.

When Kansas and Nebraska ― both very large territories ― began to petition for statehood, Southerners vehemently opposed it. Why? Under the Missouri Compromise, both of the states were in geographic areas which mandated them to be free states. So Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which nullified the Missouri Compromise and allowed the citizens of the new states to decide whether or not they would be slave states. When Missouri men sneaked into Kansas in order to illegally sway the vote towards the creation of another slave state, tensions boiled over and fighting broke out. The violence and acrimony began to spread like a cancer across the country. In 1860, despite not appearing on many southern ballots, the abolitionist Abraham Lincoln won the presidency by a large margin. One year later, the Civil War began.

The Civil War, of course, didn’t fix racism. It barely fixed slavery; instead, deeply entrenched white supremacy merely found new ways to subjugate and enslave black Americans through Jim Crow laws, rampant lynchings, economic and social disenfranchisement and incarceration.

The way we remember the Civil War is a litmus test of who we are as a nation. As Civil War historian and author Robert Hicks writes, “...as we examine what it means to be America, we can find no better historical register than the memory of the Civil War and how it morphed over time.”

The reckoning for racial justice and equality, and for national solidarity and cohesion, continues to this day. Until we have a realistic (likely uncomfortable, perhaps painful) reckoning with our collective history, we will remain stuck in the same rut. The administration currently occupying the White House seems intent on digging in even further.