Jordan's media are at a dead end and its laws are hampering journalists from working in an open environment, a report on freedom in that country revealed.

"When you read this title, it's an indicator of what Jordan's situation is," Nidal Mansour, president of the Amman-based Center for Defending Freedom of Journalists (CDFJ), told me, adding that legislation was a tool to restrict freedom.

Mansour said the report, "Dead End: State of Media Freedom in Jordan 2014," released this month by the CDFJ, found that while 2013 and 2014 had similar results indicating a relative drop in violations of media freedoms, the types of violations remained the same.

There's also follow-up to the law such as directives issued by government departments and agencies barring coverage of certain issues on the pretext they may undermine national security.

"For example, you can't publish anything about the General Security forces if the news doesn't emanate from General Security. That's a form of pre-censorship. Suppose I don't want to use General Security sources? You can prosecute me if I publish wrong information, but you can't tell me I can't publish at all," he noted.

A case in point was the capture by ISIS and later burning alive of Jordanian pilot Moath Al Kasasba with the video of the incident posted online and going viral.

Jordanian media were told they couldn't publish anything unless it was issued by the armed forces.

"We understand the dangers that may affect people's lives and have clearly stated that, ethically and legally, the right to life surpasses the right to know," Mansour explained about giving priority to saving lives if people could be harmed. "But we also said that officials should guarantee providing accurate information on a regular basis to the public, since, in principle, Jordan has an access to information law."

Adding to the stranglehold is the recent appointment of Salameh Hammad as interior minister.

Hammad, known as a strict enforcer, held several key positions at the ministry during a period of martial law and twice held that cabinet post in the 1990s.

Since its launch in 1998, the CDFJ has been very active in promoting legal awareness among, and protection for, journalists in a bid to shield them from arbitrary treatment and empower them to understand their rights.

It has provided legal assistance in hundreds of lawsuits filed against journalists and has published a handy book entitled "50 Questions & Answers: The Media's Legal Guide."

Jordanian journalists face other hindrances to their work, including physical assaults that have become common, notably in coverage of domestic hot spots like demonstrations and sit-ins.

Mansour said that while international conventions specify how security officials may deal with suspects, Jordanian officers ignore such guidelines with the result that a simple arrest could lead to an all-out physical attack on the detainee.

One glaring issue from the "Dead End" statistics comparing results for 2013 and 2014 was that self-censorship had increased.

It reached a level of over 95 percent in 2014, as opposed to 91 percent in 2013, Mansour said. The CDFJ began monitoring self-censorship in Jordan at the beginning of 2011 with the outbreak of the "Arab Spring when it recorded figures of 86-87 percent.

"It means journalists chose to install an internal censor to avert being exposed to problems or harassment, regardless of the justifications," Mansour said, adding that self-censorship was no reflection on their professionalism.

The survey found that the taboos journalists most avoided were the armed forces, the intelligence services, religious issues and sex.

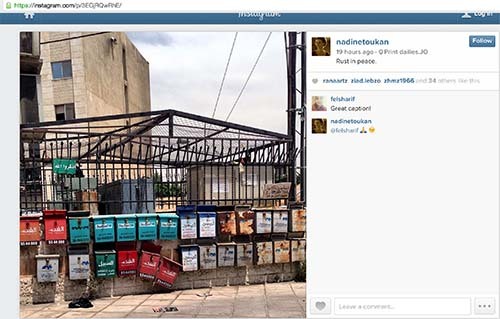

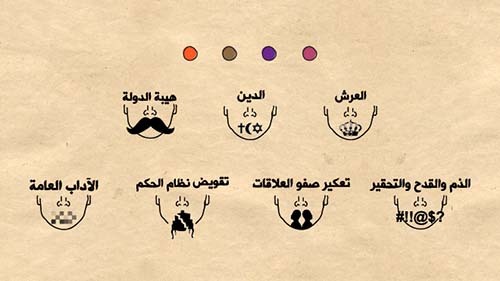

A telling graphic produced by the news portal 7iber illustrates the media's seven sins: the crown (King Abdallah II), religion, the state's prestige, slander/libel/abasement, disruption of good relations (between people and states), bypassing the state's order, and public morals.

Media's Seven Sins (courtesy 7iber)

According to the Jordanian constitution, only the king is immune from criticism. If citizens want to criticize him, they would have to change the constitution.

For the first time this year journalists avoided criticizing the king, the royal court and the ruling class, the study revealed.

A pressing threat to the media is their economic and financial security and existence - the greatest such danger in 50 years -- with leading newspapers facing bankruptcy and closure, Mansour said.

The government controls leading dailies through the Social Security Administration that owns those papers, so their editorial boards consist of government appointees.

"We say the government should not deal with the media as if they were shops. These are platforms for enlightenment and knowledge, regardless of our comments on how bad they are, or can be," said Mansour.

If the government wants to own newspapers, there's a recipe worldwide known as public service, he said, where media may receive government funding but ultimately express the people's views and where content is more important than advertisements.

On issues of corruption, Mansour was explicit: conflict of interest demeans the media and journalists.

I asked about a member of parliament who owns a TV station that she uses to further her causes as she blithely sits on the parliamentary committee deciding on media-related legislation.

"What's worse is when a journalist works at a newspaper, and doubles as a consultant at the Interior Ministry, while covering news at the very same ministry as part of his regular beat," Mansour lamented.