***

In 1899, two titans of the American journalism industry were brought to their knees by 5,000 children.

Joseph Pulitzer of the New York World and William Randolph Hearst of the New York Journal were locked in a bitter rivalry that would forever change the nature of journalism.

Hearst, who had seemingly unlimited wealth, routinely enticed Pulitzer's best columnists and editors to join the Journal by offering them huge pay increases. Pulitzer, with a reputation for journalism excellence and with the advantage of the World being first to dominate a market, weathered the rise of Hearst's Journal by playing defense. When Hearst dropped the Journal's price, Pulitzer followed suit. When Hearst began publishing sensationalized stories before crucial facts had been discovered, Pulitzer recalibrated his ethical compass and did the same.

As the two fought tooth and nail for readership, the importance of marketing rose to prominence. Never again would marketing be viewed as content's assumptive aftermath; it became and continues to be an indispensable and integral asset in all stages of content development.

Content unread is not king, it's a napkin. We know this now. But how did the realization occur?

The Spanish-American War, a 3-month conflict in 1898, captured both of their audience's attention unlike anything they'd ever seen. So Pulitzer and Hearst, seeing the war as a pivotal point in their own war for journalism's throne, spent a fortune to carve out their paper's place as the leader of content on this topic.

Months later, as they sought to recoup some of the money they'd spent, Pulitzer and Hearst raised the bulk prices for the newsboys who delivered the paper--100 copies for 50¢ became 100 copies for 60¢. And the boys couldn't get a refund on any unsold papers.

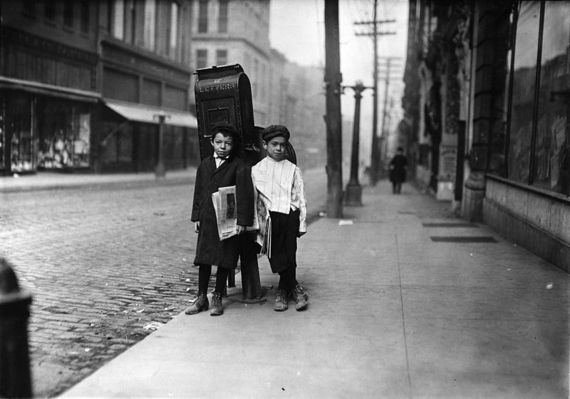

The newsboys were deeply impoverished; many were homeless and slept under bridges. When a shipment of papers came in the boys would buy bundles of them and then hit the streets, where they'd spend their entire day as miniature marketing machines. As you crossed the street on your way to work, they'd be yelling out the headlines or hinting at what you'd be missing if you didn't get today's paper. In essence, the New York World and the New York Journal relied heavily on the marketing prowess of these newsboys to promote and distribute their papers.

That is, until 1899, when some 5,000 of those newsboys went on a two-week strike and, in one of the most profound events in journalism and child labor history, brought the behemoth that was the New York journalism industry to a grinding halt. The boys protested in the Brooklyn Bridge to get attention, clogging it and disrupting the commute of hundreds of thousands of people. They held rallies and gave impassioned speeches about their plight.

While Hearst was in a far better financial position to keep the Journal afloat, both the World and the Journal were impacted severely--with the World's circulation dropping by 50%. Pulitzer and Hearst both hired people to break up the rallies and keep distribution channels open, but to little avail. In just two weeks they gave in to the boys' request, and agreed to buy back all unsold papers.

Perhaps more than any moment in the history of journalism or content marketing, this was when both fields realized how little they had without each other. While the content creators were lauded as the great journalists of their time, they now realized that even their greatest work meant nothing without the marketing distribution efforts they had previously taken for granted.

Today, even as both fields are more fused than ever, a disconnect remains between those creating great content and those who are masters at getting people to read content.

Journalism purists often look down upon those in content marketing, generalizing the field as an industry that sees untalented spammers as talented 'growth hackers,' and as a world filled with second-rate writers and failed journalists. I've met some who roll their eyes when their work is referred to as "content," as though what they are creating is somehow of such immense quality that it should never be referred to in such a disparaging way.

Truth is, just as in 1899, journalism and content marketing need each other. As investigative journalists tell some of the most important stories of our time, the publication they work for is often cash-strapped, underpaying those journalists, and too busy or blind to break free from its antiquated ways of distribution--maybe sending truly brilliant content out a few times via their social media channels and calling it "a strategy."

Meanwhile, those in content marketing are creating cross-sector partnerships with brands who are building out their own new media platforms. Coupled with this, they're using the latest methods and tools to track and assess reader behavior, they're focusing not only on growing an audience but nurturing it so it's less likely to be influenced by a competitor, and they're developing comprehensive post-publication outreach initiatives--initiatives that enable them to get more people reading even a mediocre piece of content than the journalist (or the publisher) typically can get on a piece they may have risked their life to write.

Of course, the disconnect isn't as stark as it may seem. Many journalists, especially those just getting started, realize the two hats they must now wear. There are exceptions, but modern journalists are increasingly realizing that the writing of an article no longer ends upon publication or even once they've shared the piece within their networks. It never ends, really. Today, each piece--for those at the intersection of journalism and content marketing--becomes part of an empathic ascending continuum that cares about the story, the audience for that story, and the audience for the next story.

To be clear, journalism and content marketing aren't on different pedestals within one field; they are standing on the same pedestal. And if what's happening now is any indication of what's to come, neither will reach its potential without significant help from the other.

***

See also:

-Photo: 7-year-old newsies, 1910. / Wikimedia Commons