We need to have a prolonged discussion on the purpose of education. Everyone needs to be part of that conversation -- parents, kids, teachers, administrators, everyone.

Teaching for their glory, not ours.

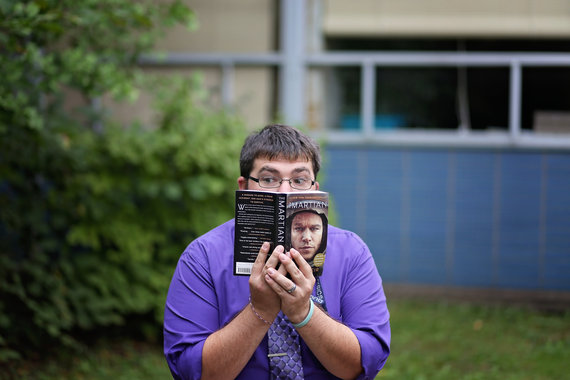

"In my heart, I've always been a teacher. I have this tendency to explain things to people -- whether or not they want me to. I started in the classroom eight years ago thinking everything was great and that I was going to change the world, but everything came crashing down pretty quickly. It took me awhile to understand that I had a lot to learn. I'm a much better teacher now and keep getting better as the years go by. But I also acknowledge that I know less and less, and the acceptance of that makes me better at what I do.

You don't get into teaching for the glory. I don't drive my Ferrari to school and then peel out after the bus to go home and swim in my pool of money. We're here to glorify our students, to show the work that they've done and how much better they are than they were yesterday. We elevate our kids and put them out there so everyone else can cheer on what they do."

Making the "aha" moments last.

"Woodland Hills is a very interesting district. It runs the entire socio-economic gamut, making the situation a huge argument for individual education. There's a lot of opportunity and growth that can come from showing the kids what lies beyond their communities. That's been a huge push for me: I want them to see what happens outside of their own spheres. The more I can relate my classroom to the outside world and help them realize that they're part of something bigger, the better I am able to do my job.

But I want them to be the ones making the discoveries. We talk about these 'aha' moments, where the kids have these revelations about something they didn't know before. I don't really like the 'aha' moments -- I don't think they last. I prefer the 'holy crap' moments, where the kids look at something they're doing and say, 'Holy crap, this is so cool!' That kind of passion and interest expands outward and helps them see something they're interested in and explore it further. I want my students to find their passions, and the best way I can do that is by facilitating those discussions and bringing in those outside sources."

A question to change the discussion.

"I am a great supporter of the Common Core because it emphasizes skills. But I have a tremendous amount of difficulty grasping how we can come up with standards for all of education when we have yet to have a prolonged discussion on the purpose of education: why do we send kids to school? Everyone needs to be part of that conversation -- parents, kids, teachers, administrators, everyone.

Up until the mid-nineties, the purpose of public education was to get kids ready for the workforce. We wanted kids to be successful, productive workers -- but that's not really true everywhere anymore, especially with the push toward Common Core. Are we looking at education to benefit society or individual students? Do individual students have different needs from education than society?

Based on our service-oriented economy, shouldn't we be training kids to be waiters, web developers, or hotel managers? But we don't -- we give them a general education in the hopes that whatever they choose to do, we've equipped them to be successful there. And that's what I want to do. I don't want to push them in one direction or another, but I want to equip them with problem solving skills and expose them to things in the world that they wouldn't otherwise be exposed to.

If you ask kindergartners what they want to be when they grow up, they generally give the same five responses: doctor, lawyer, policeman, fireman, and teacher. That's about it -- because they don't know what else is out there. Every year, I casually tell my students that there's a program through the University of Nevada in Las Vegas where they design roller coasters. That's the whole major! And the kids are totally blown away by that. They don't realize that's something you can study in college, because it's just not something they've been exposed to. But knowing you could be a roller coaster designer changes your whole outlook -- you could be anything."

The voice that's missing.

"The thing that concerns me about education in general is how teacher voice is ignored in this discussion. We don't do that to doctors or lawyers. We take their opinion as expert, and we seek it out -- but with teachers, we go the opposite way. Teachers, with few exceptions, are very rarely seen as experts in education, and that's a huge problem when it comes to things like standardized tests and data. Testing can definitely have value, but it's a question of whether or not that data is being used correctly. It's only one measure of an incredibly complicated system, but for some reason, we see it as the only measure.

There was a picture cycling around on Facebook of six women that weighed the exact same -- and they all looked completely different. Their weight was not an accurate representation of the health of any of those women because there are simply too many other factors involved. And standardized tests are the same way. Kids are so incredibly complicated that to try and come up with a number or test score is a drastic oversimplification, and it doesn't do justice to the students and their abilities -- or the teachers and their abilities.

In the end, the tests are two weeks out of the year, but getting to watch those kids grow and to see them find something that really interests them -- that's magic. Now that I have kids of my own, I think about it in the same way. There's almost nothing better than having your own kid say, 'Hey Dad! Check out this super cool thing that I just learned!' I get to do that every day. And yeah, there are frustrations, but there are frustrations with anything. Would it be nice to be paid more and heard more? Absolutely. But we do it for the kids. Because while they're having their 'aha' and 'holy crap' moments, so are we."

Photography by Heather Nyapas.