Mrs. Kudrun was excited. The petite, middle-aged director of the Hotel Kolovare in Zadar pulled me aside. "Sprov! Chisspipple!" she hissed, pointing to a group of smartly-dressed gentlemen that were bustling into the lobby. "Chisspipple" she repeated proudly.

I was confused. "Cheese people? What? You have cheese people here?"

"Ksprov? You don't know Ksprov? Chiss!"

"Oh, chess! You have chess people here! Kasparov? Garry Kasparov?"

"Yes, Ksprov! Big friend of Croatia. Here to play chiss."

It was 1996 and the few friends that Croatia had seemed unlikely to find themselves in Zadar, still emerging from the embers of war-torn then-Yugoslavia. I had no choice. Zadar covered several pages in Lonely Planet's third edition of Eastern Europe and I was the author hired to update it. The National Tourist Board arranged for me to stay in the Hotel Kolovare and, as it was unclear whether any other hotel was open, who was I to argue?

Like most hotels along the coast, the Kolovare was housing refugees from the interior who had fled Serbian control several years ago. Bedraggled men slumped around the bar and sunk into the tattered '70s-style armchairs in the lobby. Some were quiet and morose, madly chain-smoking. Others were belligerently noisy, semi-drunk, bellowing and making loud, probably crude jokes to glum waitresses.

Meanwhile, hotel staff scurried around the dining room rearranging tables into a circle, preparing for a simultaneous exhibition that pitted legendary champion Garry Kasparov against 20 local players. The dangling cubes overhead were removed allowing the light from bare bulbs to penetrate the shadows. Men slowly filtered into the dining room, murmuring to each other and nodding gravely.

"Why here?" I whispered to Mrs. Kudrun as the players and onlookers assembled at and around the tables. "Zadar is origin of chess in Croatia.Played here since 1385." "But why now," I asked. "Morale," she said. "Make everybody happy."

From what I had seen of the beleaguered city, morale could definitely use a boost. Zadar was hit early and hard by Serbian artillery and the shelling lasted sporadically from 1991 until 1993 when the Croatian military pushed the gunners far enough from the city that the residents could start to piece together a normal life.

The return to normalcy was still very much a work-in-progress. The predominantly Serb hinterlands, the Krajina region, had been bitterly contested and now the infrastructure was in ruins, the population had fled and dark stories of war crimes circulated on both the Serb and Croat sides. Everyone I met in town seemed to smoke too much and sleep too little.

Finally Kasparov entered the dining room like a fresh breeze, brimming with confidence and ready to play the chess world's version of Stump the Stars. And he did seem stumped from time to time but not for long. In the 3 hours and 20 minutes it took him to dispatch his opponents, he rocked on his heels, leaned over the tables, rubbed his eyes, scratched his chin, mumbled, shook his head, blinked rapidly, gazed at the ceiling, exchanged knowing glances with his entourage. I began to understand why chess was covered in the sports section of the newspaper. At some tables, he made his move promptly and hurried on while other players caused him to linger. "He tries to finish quickly," Mrs. Kudrun pointed out, "because he will get tired and maybe makes mistake."

Ranging in age from ten to 60, the youngest were eliminated first. After each player conceded defeat, Kasparov shook their hand genially and signed the scraps of paper upon which they had recorded their moves. After three hours there were still seven players left to puzzle the champion. Kasparov made his move at one table, murmured something and a hubbub ensued. He spent a few minutes explaining why the game was over and moved on, steadily picking off his opponents. The last to fall was a somber middle-aged man with glasses and light brown hair. Kasparov shook more hands and left for his room, probably to rest.

The following day he made an extensive tour of the war-torn Krajina region.

I've returned to Croatia many times over the years and so has Garry Kasparov. I had heard rumors that he had a house on the Istrian coast but it appears that the chess king and newly-annointed Croatian citizen is based in the Dalmatian town of Makarska. Reports are that he may even set up a chess academy in Croatia.

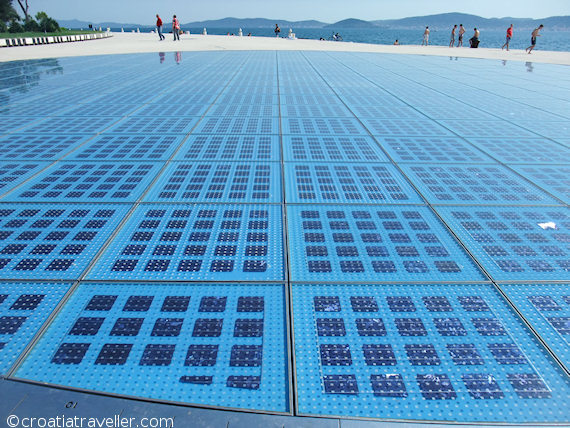

And Zadar? Zadar is doing just fine. The pockmarked buildings and tattered monuments were quickly repaired and the ancient streets are now alive with bars, cafes and excellent restaurants. The Kolovare has been overhauled and turned into a four-star hotel. Signs of its recent, painful past have been removed but plenty remains of Zadar's days as a Roman municipality and fortified Venetian port. In a tribute to the city's resiliency, two new installations are resoundingly modern. Zadar's Sea Organ and Sun Salutation, both by Nikola Basic have transformed a dull waterfront into a 24/7 sound and light show.

Chess champions and everyone else may have aged in the last 18 years but somehow Zadar has never seemed so young.

Find out more about visiting Zadar here.

Zadar Sea Organ