Tom Sachs, Photograph by The Selby

Tom Sachs, Photograph by The Selby

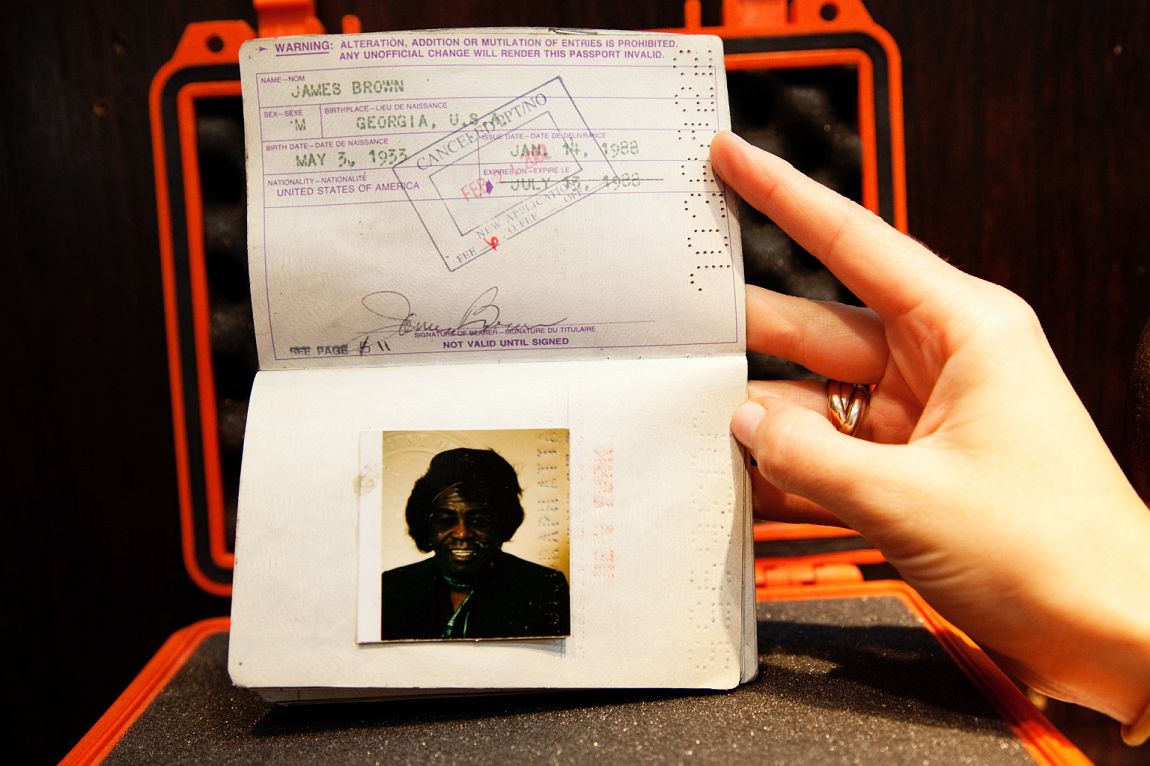

After a few years of tinkering in his studio, Tom Sachs has resurfaced with a new show entitled Work at New York's Sperone Westwater gallery filling three floors with art exploring as many creative tangents: a series of pyrographic works, using a wood burning-etching technique; a foam core crafted collection based on Sevres porcelain; and a series that pays homage to James Brown, with a JB listening station, his Last Supper packed in a microwave, and a framed array of JB's hair products.

Sachs had cited James Brown's work ethic as an inspiration for the show, so I took him to task for being late for our meeting and disappointing Brown's high standards for punctuality.

"When Brown fined his workers for being late it was contributing to a culture of punctuality," explained Sachs in defense of the Hardest Working Man in Show Business. "He fined them for missing a beat, he used punctuality as a percussive element: to be on time, to keep time; not miss a beat."

Sachs runs his Vulcan smithy of tinkerers like a boot camp, with red beans and rice every Monday.

"Rather than a prison fantasy it's more a utopian fantasy. More Amish. You can leave," he forewarns me, "but you might find that the outside world may not be as inviting."

Tom Sachs' tribute to James Brown: Tom Sachs 'Please, Please, Please', 2011 mixed media 162,6 x 55,9 x 35,6 cm overall Courtesy Sperone Westwater Gallery

Tom Sachs James Brown's Last Supper, 2009 mixed media 172,7 x 106,7 x 57,2 cm Courtesy of Sperone Westwater Gallery

Tom Sachs, Photograph by The Selby

Many of Sachs' artworks retain a quasi-functional element, and he often appropriates objects to demonstrate rituals in people's lives. I ventured that his use of diagrams, maps, floor plans and lists might hark back to his childhood, playing with models perhaps?

"I want to use this opportunity to debunk the myth immediately that I'm as organized as I might look," he tells me, further shattering any suspicions I might have had of his discipline. "It's my way of battling entropy. I live an incredibly chaotic life. In recent years, I've made an incredible effort to eliminate chaos from my life. But it's also where I find inspiration, so it's a question of finding balance. I don't know what Donald Judd's life was really like because I never met him -- but I imagine someone with furniture like that would have a very ascetic existence."

"I grew up very unhappy and learning disabled, a terrible athlete, failing classes constantly, always having to go to summer schools, profoundly unsuccessful," Sachs summed up his childhood, "It might have been diagnosed as dyslexia or ADD -- but when I think back, it's really that I hadn't found my calling yet."

Might he have found his calling in architecture school to channel his wavering interests? Sachs scoffed at this, "No, architecture training was completely worthless. Sculptural building is where I learned all that... and I spent some time as a construction worker."

Sachs can afford to thumb his nose now at architects too lofty to get their hands dirty with any kind of actual building. At the Architectural Association in London, where he studied, Sachs remembers how his classmates tried bribing him to finish their technical studies project for them. "I told them to fuck off, so they probably hired someone else to do it. But I bet those are the bitches out there making terrible buildings."

Tom Sachs Spade, 2010 - 2011 camouflage cloth, 200 x 10 x 1,9 cm Courtesy of Sperone Westwater Gallery

Our conversation meandered into Ant Farm, the Design Build movement and the corrosive action of urine on corner walls of fancy architecture, but I thought James Brown might have disapproved of our attention dissipating, parenthetical digressions so I returned our swerving line of query back to the ubiquity of branding, and its impact on our cultural consciousness: Sachs, has a scaled-up version of a McDonald's coffee stirrer in the show -- it's like a paddle with a weaponized spade-tip that could be used in agriculture or war... but Sachs is likely taking a dig at its proletarian usage, "for cocaine."

"I've been repulsed by the promises and the perceived obsolescence that advertising creates in our lives, the insecurities of not having something -- and that buying the product might make our lives better -- but simultaneously, I'm attracted by the glamour, beauty and power of brands. I'm not exclusively critical of them -- I'm a complicit critic. A participant in the cycle."

Tom Sachs, Photograph by The Selby

If not entirely immune to the latest Prada handbag then, Sachs is far more consumed by his next project of a make-belief odyssey, 'Space Program 2.0: Mars,' about to transform the cavernous interior of the Park Avenue Armory in New York next year. Sachs also makes seductive cabinetries for his NASA projects, with knobs and dials exquisitely detailed from an era of machine hardware, rendering them as fetishized historical artifacts. He speaks wistfully about the golden age of machine design, which he considers to have been dead by 1974. "So discouraging for me to see how amazing the software has become and how degraded the hardware has become, and how we've kind of given up."

"When I was in architecture school -- I thought I could contribute to the world by making beautiful buildings. I got discouraged and dropped out and said fuck it -- I was going to enjoy my life and make what I really love to do... make the best sculptures I can -- and communicate the way I do things as ethically as possible -- building things to last," said Sachs earnestly. "I make things out of paper, foam core and non-durable materials but I do everything in my power to imbue them with value and meaning so that they can live on beyond me."

Tom Sachs Swans, 2011 epoxy resin on mixed media, 35,6 x 40,6 x 40,6 cm Courtesy of Sperone Westwater Gallery

Coming full-circle, back to Sachs' original cobbled-together hot-wired artifacts he's best known for, is his new series of beautiful foam core bricolage that imitates the highly coveted 18 c. porcelain collections produced by a factory in Sevres, founded by Madame de Pompadour, mistress of Louis XV (c. 1745). Known for her fashionable tastes, she set the Jones' ablaze with envy, starting a mad collecting rush that inflated prices and resulted in buyers paying more for a tea set than an entire farm. The huge inequity eventually led to the Goldman Sachs 1% of the 18 c. losing their heads in the revolution. But later, even Napoleon, not without vanity, ordered his customized set in Empire style for his empress Josephine.

The value of cultural artifacts will rise and fall with the times, and Sachs is particularly interested in why. At the Met, the value of objects, ornamental and functional, many thousand years old, seem to converge. "So many hierarchies shift," says Sachs, "History paintings were the most valuable, like Oath of the Horatii, a work by French artist Jacques-Louis David (1784), then below that were landscape paintings and portraits, and below that, the genre paintings of poor people. It wasn't until Manet did a portrait of a prostitute, elevating her, that it threw that hierarchy on its head... today, anything functional is super downgraded."

"If I use something that can be used as a chair, it's worth a lot less than a painting I would make." A chair is more accessible to the public, lacking the mystique associated with art.

Tom Sachs, Photograph by The Selby

"How did you manage to get James Brown's hairbrushes?" I asked, referring to another set of functional objects, their value skewed by another form of mystical reverence.

"That's something that happened accidentally because when the vampiric auction house took the worldly possessions of a historic figure to capitalize on his infamy -- letters from prison, shameful objects that should have been thrown away, I tried to rescue some of the things that capture his greatness. It was a garbage bag full of crappy hair products."

"The entire piece is a frame for that photograph of the top of JB's head. And you can imagine him taking it to his hairdresser, telling him to make it look like this... "

I blasphemously questioned whether it was all his real hair. Not a wig, then? Though Brown hadn't been feeling well he was a man that visited his dentist the day he died; it was real hair.

"He said all man needs is good hair and good teeth," said Sachs approvingly. "They are like reliquaries -- it's not about the artist recontextualizing it -- it's all about him and his greatness," said Sachs, reflecting on the divinity of the Grandfather of Soul. "It's no difference than going to Turin and seeing the shroud -- putting a euro in the box at church so it lights up..." JB would no doubt have found Sachs' tribute a perfect stage for a second coming.

x373.jpg" alt="Tom Sachs, Photograph by The Selby" width="560" height="373" />

x373.jpg" alt="Tom Sachs, Photograph by The Selby" width="560" height="373" />

James Brown memorabilia - Tom Sachs, Photograph by The Selby

Text & Interviews: www.KisaLala.com