Bass-baritone Keith Miller is a former football player and a graduate of Philadelphia's Academy of Vocal Arts. He joined the Metropolitan Opera in 2006.

Art, the Arts & Policy, is a cultural, anthropological questioning of how we are changed by art, whether we are aware of the change, or simply live without naming it. With that said, the first introduction to this treatment of the opera and Keith Miller is a disclaimer, though not an apology: I'm not an art critic or reviewer.

The second introduction is for familiar context: The opera was first delivered to me as a concept, a remote thing to "appreciate." Later, it only brushed by, a close call in the form of a canceled field trip at T.W. Browne Jr. High School in Dallas, Texas. Years later, I heard it, listening to two Metropolitan Opera singers just five feet away from me in an offbeat salon session (P&P Studio) near Union Square. I was blown back by the down-to-the-soul storytelling. (The offbeat part was the billing, "French Open Men's Final, to be followed by the "Spring Sojourn" of songs in the afternoon.) (Left: Keith Miller)

Why didn't they tell me that this was what opera was about? I can't blame them. They were mostly unwitting guards, obedient to class and "culture," shielding art from me in the name of respect for it. Others do this guarding on purpose.

In contrast, let's start with blank, uncomplicated respect (as artists, observers, everyone). This is precisely where I begin my conversation with Keith. His presence emanates respect far beyond demeanor as we sit in a lobby just around the corner from Lincoln Center Plaza.

I imagine this kind of respect as the root of professionalism, and that's what emerges as we begin to talk: you feel his concern for "the other." What you experience is an unmistakable, controlled fission that powers what he delivers on the world stage. I'm now led to learn the mind of the professional artist, not as much about the trade as the professionalism of the artist.

A quick Google search for "Keith Miller opera" lands you in a trail of stories about the football transition. You should read them, despite the clichés we can't seem to avoid on the seeming dichotomy. I respect those stories. A couple of them are well-told, and the history is real. But, time isn't friendly: Let's start a new thread.

I asked Keith three questions, for a glimpse into how he works.

When you first realized you could make a life of opera, but still didn't "know" that (not to be confused with being unsure, but simply new to the field), how would you describe the path and the unexpected people and/or experiences that have helped you advance?

There were so many people who helped and encouraged me. Lucy Thrasher, David Hamilton, Matt Morgan, Kevin Short, Tanya Kruse and many others. I basically trusted everyone and everyone had some really wonderful advice to give which helped pave the way for me to get an education and make the opportunities that I have now. Really, the opportunity is what I wanted more than anything. To show everyone and myself that their faith in my "apparent" talents was not in vain. That I would at least work my tail off to thank them and the rest would be up to fate, luck, chance and God. All of these things still apply to my life today and more than ever having faith is the continual challenge. The saying of "make me weak" when you ask for strength is so true to what I always say, that things aren't to be found, but to be made.

When did the true demands of the opera hit you, beyond the intellectual understanding we might be able to imagine?

I sang the role of Sarastro at AVA, it was a good assignment for me and I became greedy and thought that I could throw my hat into the mix for Faust as well. It hit me very late at night in David Lofton's studio that I wasn't even remotely close to understanding what I was doing or how much work it would require to sing this kind of role. It was daunting, overwhelming, intimidating and yet I loved that the gauntlet had been thrown down. I had to look myself in the mirror and say, "what are you made of now?" What's it like to know you know nothing about anything and what are you going to do about it?"

That's when the real work began, and the questions of whether or not I could make it or succeed came mostly from myself and whenever I felt afraid of failing, or doubtful or over my head I just stayed in the studio late nights and worked.

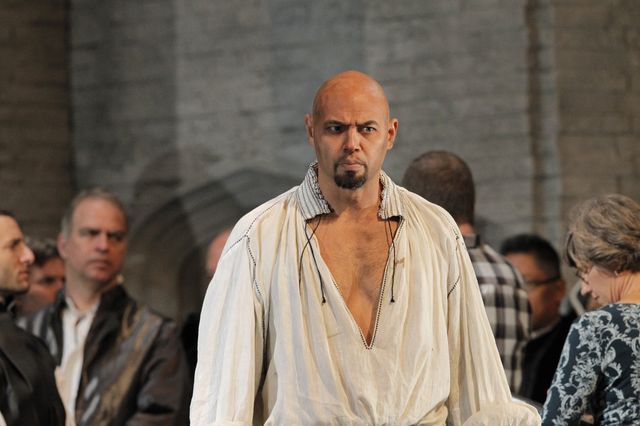

Keith Miller as Lord Rochefort in Anna Bolena, by Gaetano Donizetti.

Keith Miller as Lord Rochefort in Anna Bolena, by Gaetano Donizetti.

I had a promise to keep and people whom I wasn't going to let down. I still represent all of those people and everyone who ever gave me a chance. It's not my past, but even now, the mirror shows the same challenges and questions and the answer is always the same: Work, work your butt off Keith, just work.

"Art, the Arts & Policy"...You are a personal case in point of art forcing a visceral and personal policy change. How have you seen opera, and the Met in particular, influence the ways we think and move?

I truly believe that the Met in particular has helped lead the way in bringing opera to the forefront of popular live entertainment. Opera is like gold or oil or any other commodity, it's needed, it will always be needed and the value of the stock is based on the quality of what our society places priority on. I do not think that anyone, anyone who sees Le nozze di Figaro can walk away from that experience unchanged. The theme reflects our humanity so poignantly. We all battle with desire, need, want, greed, envy and even when we have failed, the power of forgiveness and love can overcome anything. It is an unseen force that the finale brings to us in both text and the most beautiful music known to humanity.

It is this that makes opera valuable.

It is the reminder that love is our greatest gift. That forgiveness and understanding cannot be bought, traded or sold. It is the memory of a mother's hug and a father's tear. It is why we are alive. It is the only gift we posses no matter where we come from, and it lives in the art, in the music. It is more than heard, it is felt, and visualized. I don't think we influence an audience, I think we awaken their soul, set to music. Who doesn't need this?'

...

Keith made me think about what professionalism must yield: inspiration and innovation.

When asked what inspires him, he only refers to the work, reminding me of a classic artist and workhorse, Alfred Hitchcock (see 22:00). Keith notes , "The music is the inspiration. People that have to look other places for inspiration, they've lost the core essence of what it takes to be in this business."

On innovation, I note how he trains -- in the multidisciplinary method required for modern opera, including a heavy dose of physical training.

Early in his career, he was encouraged to leave physical training behind on the grounds that it would hinder the voice. He counters by reasoning through 1970s pro football. It was argued then that weight training would limit agility -- a non-starter today, literally.

Here, innovation mythology is turned inside out. Innovation isn't a goal in itself as posited by one book after another encouraging us to "innovate!" Instead, it's the by-product of knowing your environment, meeting its demands and beating competitors. The top competitor is an innovator, by definition.

I think the biggest achievement in all of this is ours. When we see people from unexpected quarters do amazing things, it often forces us to change policy.

A case in point: The United States, the big brand for innovation and inspiration, is perhaps the world's youngest fully participatory democracy, 48 years old, after widening our legal view of humanity. This policy was forced by a lot of people, especially by artists. Each possessed some unexpected way of making things work differently.

Keith Miller makes things work differently as he puts us to thinking and dreaming at once. That's a unique effect of art on the spectator. On stage, it's a moment of discovery for everyone, including the performer who has prepared enough to dive into the infinities of a role. As we alternate between the roles of spectator and performer, we owe each other inspired work before taking the stage, the kind that lays weaknesses bare, but follows with a view into our capacity to accomplish unreal things. Keith is a welcome study in this conversation on our humanity.