The thick, slimy brown ribbons are notorious for tangling the ankles of beachgoers and rotting in pungent piles. But kelp, according to its growing fan base, could also prove potent in protecting the health of oceans -- and us.

"We've got some bad water heading our way," said Betsy Peabody, founder and executive director of the Puget Sound Restoration Fund. In April, Peabody's small organization in Bainbridge Island, Washington, won a $1.5 million grant from the Paul Allen Family Foundation to investigate how cultivating the seaweed might help lessen the impacts of ocean acidification.

Other research has hinted at the sea plant's potential to prevent toxic algal blooms and provide habitat for marine life, as well as even generate sustainable energy and food while preserving scarce fresh water for humans.

"Kelp is a game-changer," said Bren Smith, owner of the Thimble Island Oyster Co., which grows a vertical farm of oysters, scallops, clams, mussels and kelp in Long Island Sound. "It is so resilient, fast-growing and does all of these powerful things."

Smith, too, referenced kelp's capacity to sweeten souring seas.

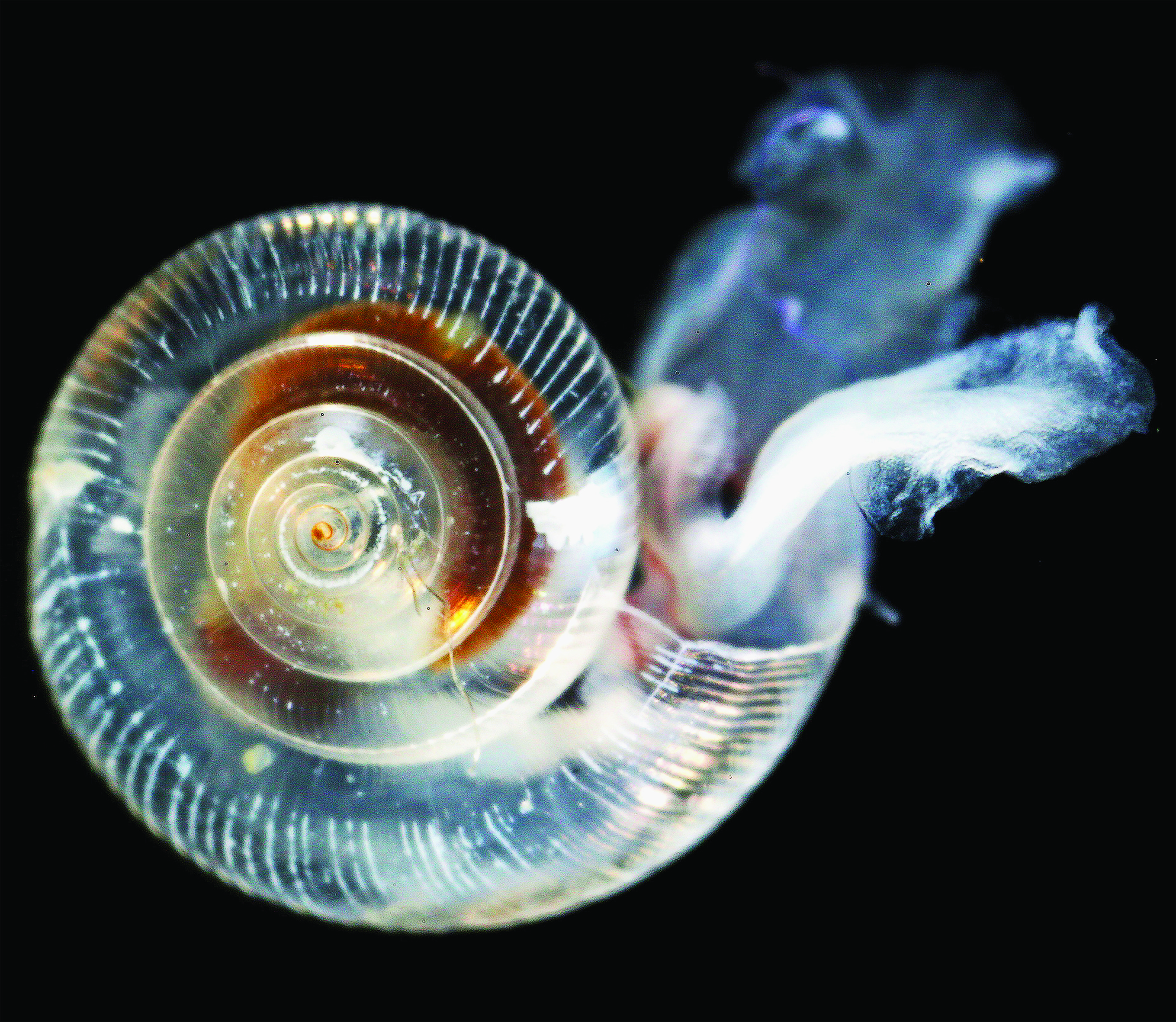

Rising levels of carbon dioxide are not only altering the global climate, but also changing ocean chemistry. A quarter of the greenhouse gas belched by coal and other fossil fuels is soaked up by seas. The result is increasingly acidic water that carries fewer carbonate ions, critical building blocks for the skeletons and shells of many valuable and vulnerable sea animals such as clams, crabs, lobsters, shrimp and sea butterflies.

No larger than a grain of sand, the latter snail-like creature is a staple in the diet of marine animals, including sea birds and salmon, around the world. Off the Pacific Northwest coast, about half of sea butterflies carry partially dissolved shells, deformed fins and other impacts of ocean acidification that affect their ability to swim and avoid predators and infections. Researchers project that three-quarters will be affected by 2050. A 10 percent drop in sea butterfly numbers translates into about a 20 percent drop in the body weight of mature salmon.

"Salmon are food for orcas, seals and sea lions. Salmon are food for us," said Peabody, adding that sea butterflies are also an indicator of how ocean acidification may impact other species. "We need to fully understand what is in our tool box and what isn't to mitigate these effects."

She and other scientists recognize the urgency of the situation. The world's oceans are already 30 percent more acidic than than they were at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, and are predicted to be 150 percent more so by the end of this century. The increasingly corrosive conditions can also kill coral reefs, scramble fish behavior and make many sea creatures less resilient to pollution.

The Puget Sound, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, is currently one of the most acidic water bodies in the country. Experts warn that it is also a harbinger of things to come elsewhere, especially along shorelines where more acidic water naturally upwells from the sea floor.

With the help of federal, state and university scientists, Peabody and her team are now preparing to deploy three acres of twine seeded with budding sugar kelp in Puget Sound's Hood Canal. Once the array is submerged, they will begin using sensors on boats and buoys to test the acidity of water before it enters the site, and then again as it leaves. They should have results by 2019.

Walt Dickhoff, division director at NOAA Northwest Fisheries Science Center, a member of the grant-funded project team, likened the strategy to creating green spaces in cities. Trees, lawns and seaweeds like kelp all act as natural sinks for carbon dioxide.

"This is the first attempt to actually counteract ocean acidification," said Dickhoff, noting that if the pilot project is successful, native kelp species could be enlisted to protect vulnerable coasts around the world. "As ocean acidification gets worse, which is the direction it is going, can we do something to mitigate it, at least in local places?"

Of course, ocean acidification is a far bigger problem than can be simply solved by rafts of seaweed, warn experts. Cuts to emissions remain critical.

"In the Asia Pacific, a lot [of seaweed] is used in food and is thus simply respired to carbon dioxide in a short time span, so it does not contribute to carbon dioxide mitigation," John Beardall, an expert in seaweed and ocean acidification at Monash University in Australia, wrote in an email to The Huffington Post. "However, if converted to biofuel or used to make chemicals that would otherwise be derived from fossil fuels, then we could reduce our fossil fuel consumption and thereby mitigate some of our carbon dioxide problems."

Dickhoff noted that his team, partially in an effort to make the strategy economically sustainable, will look into harvesting the kelp for products such as food, fertilizer, animal feed and biofuel.

Growing kelp could pay off in other ways. Harmful algal blooms, for example, are estimated to cost the U.S. $82 million or more per year. The toxins they release kill fish, cause neurotoxic shellfish poisoning and contaminate drinking water. But macroalgae, which includes kelp and seagrass, can harbor bacteria that fend off the growth of toxic algae, explained Vera Trainer, program manager of the Marine Biotoxin Group at NOAA's Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle. She recently completed a study, not yet published, that found areas of Puget Sound that have generally escaped harmful algal blooms are also rich in seagrass.

"There's chemical warfare out there in the biological world," she said, adding that more research needs to be done to determine the relative algae-defeating potential of different types of macroalgae.

Seaweeds such as kelp can also absorb nitrogen, which runs into waterways from lawns, farms and septic systems, and feeds algal blooms. Meanwhile, ocean acidification itself has been show to increase the frequency and toxicity of harmful algal blooms, added Jan Newton, an oceanographer at the University of Washington and another member of the team.

"We're trying to turn a negative into a positive," she said. "There could be a lot of benefits coming out of kelp."

Among those benefits, according to Smith, is also a cheap, healthy and delicious food that is easy to grow and resilient to climate change. He predicts kelp could become the "new kale." (He noted that the kelp farmed to remediate pollution -- including heavy metals -- would not be put into the food system.)

"Kelp requires no feed, no fertilizer, no arid land and no fresh water," added Smith, who once caught factory-fished for McDonald's and now calls himself an "ocean gardener."

He pointed to the devastating drought in California, where irrigation for land-based agriculture accounts for 80 percent of the state’s water use.

“Ocean greens just don’t require it,” he said.