The morning of the 2010 Bay to Breakers run in San Francisco, 52-year-old Ken Byk pulled on an orange Bucknell University T-shirt, dropped off his golden retriever Riley at a friend's house, then made his way to the starting line.

Several friends were supposed to join him, but all bailed out for various reasons. Byk had a decent reason to give up, too -- he'd gotten winded on his one long training run.

He wasn't really worried about it, though. It happened in Lake Tahoe, where the elevation is 6,225 feet. He kept plenty active as a skier, snowboarder, hiker and, yes, frequent runner. In fact, he had no trouble covering shorter distances. And he'd run plenty of 12Ks before.

That same fateful morning, Dr. Ruth Rodgers and her husband Andy started farther back in the pack. They preferred being closer to the front, but they'd gotten stuck in traffic on the way to the event.

Byk and the Rodgers family had never met. In fact, they wouldn't get to know each other for more than a year.

But because of when and where their paths crossed that afternoon, Byk is alive today.

As we kick off CPR & AED Awareness Week -- and the start of CPR & AED Awareness Month -- it's my privilege to share their amazing story.

***

Byk crossed the finish line, just like he expected.

The sensor looped to a shoelace registered a time of 1 hour, 19 minutes and 27.37 seconds, only about 10 minutes slower than he'd clocked in other 12Ks.

A few steps later, Byk dropped dead.

Sudden cardiac arrest stopped his heart. He collapsed to the ground and others frantically called for help.

About that time, Andy and Ruth Rodgers crossed the finish line. Andy saw the commotion around Byk and told his wife, "I think that guy needs your help."

Ruth had been an Olympic rower for the United States in 1996 and 2000. She'd since become a wife, mother and anesthesiologist. She routinely performed CPR at work, and had done it many times out of the hospital. Now it was time to try again.

When she reached Byk, another woman had a finger on his carotid artery. "There's no pulse," the woman reported. Ruth told her to begin chest compressions.

Soon, others joined the fight to save this stranger's life.

***

Ruth quickly emerged as the coordinator.

In addition to taking a turn among the carousel of compression-givers, she made sure others gave quality compressions. That is, she monitored Byk's pulse to see if the compressions were hard enough to truly pump his blood and provide oxygen to his brain.

Ruth constantly coached people to push deeper. Some weren't strong enough to begin with, or were just worn out. They also battled a natural inclination not to push too hard. It's logical, but wrong -- any CPR recipient would gladly trade broken ribs for a beating heart.

As this played out, Andy Rodgers took on the role of bouncer. He pushed back gawkers, including a newspaper photographer trying to do his job.

***

After roughly 20 minutes, paramedics arrived with the lifesaving "bag." It included an automated external defibrillator (AED), intubation equipment, an IV setup and other medicine.

The AED registered no pulse, then delivered the first shock. Once the machine said it was OK, Ruth and team continued giving CPR. This scene repeated for three rounds of shocks. Ruth then put the breathing tube in his mouth and the IV in his arm.

At least a half hour had passed and Byk's heart still wasn't beating regularly. People suggested she give up.

The thought never entered her mind.

"He just finished this race," she thought. "So he's got to be able to survive this."

The paramedics who took Byk away in an ambulance weren't as convinced. When Ruth asked which hospital they were headed to, the man gave her a crazy look.

"These guys never make it," he said.

***

Ruth never did find out where the stranger was taken.

The next day, she called several likely hospitals and asked about the guy who collapsed at the finish line of the Bay to Breakers. Nobody gave any answers.

She scoured news reports for about two weeks. She checked obituaries, seeking mentions about the finish line. Race officials were of no help, either.

"I just figured that he'd died," Ruth said. "I was sad. You're always sad when you try hard to keep someone alive and they don't make it. I don't think that kind of thing ever leaves you. I thought about it pretty often the next year."

A few days after the 2011 Bay to Breakers, her direct line at the hospital rang.

"Do you remember that guy at the Bay to Breakers who died at the finish line?" a man said. "That was me."

Stunned doesn't even begin to describe her reaction.

Fearing it was a dream or a cruel joke, she asked him to call back in five minutes.

***

Paramedics had taken Byk to the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center.

By the time he arrived, he'd gone into cardiac arrest a second time.

Tests showed that Byk had one coronary artery 99 percent blocked and two that were 90 percent blocked. Another was in bad enough shape that doctors performed a quadruple bypass.

During the operation, Dr. Scot H. Merrick, chief of adult cardiothoracic surgery, examined Byk's entire heart. He was surprised to discover how healthy the rest of it was.

In retrospect, Byk had been a ticking time bomb.

He thought he was in the clear because his lifestyle factors were all in check. He exercised plenty, maintained a healthy diet and didn't smoke or drink. His cholesterol was normal and, for many years now, his blood pressure was controlled by medication.

However, both his parents are heart disease survivors. His father had coronary artery disease and more recently has dealt with mitral valve prolapse. His mom has atrial fibrillation, pulmonary hypertension and recently also was diagnosed with coronary artery disease.

"I naively thought that since A (lifestyle factors) was no and B (symptoms) was no, then I could forget about C (family history)," Byk said.

***

He went home just six days after the operation.

That first night was excruciating, between the pain from his surgery, his three broken ribs and a raging fear that he wouldn't make it through the night. And there was this: His parents moved in to help care for him, and he didn't want them to know how much he was hurting.

"I tried getting out of bed without moaning and groaning," he said.

Byk went from walking in his house to walking his block. Within a month, he'd made about a 70 percent recovery, enough for him to drive and his parents to move out. Other milestones piled up: Walking on a treadmill, then walking on asphalt.

By February, he was ready to start running again. He even set a goal of running the 2011 Bay to Breakers.

When he pulled out his sneakers for his maiden training run, the finish-line sensor was still on the shoelace.

***

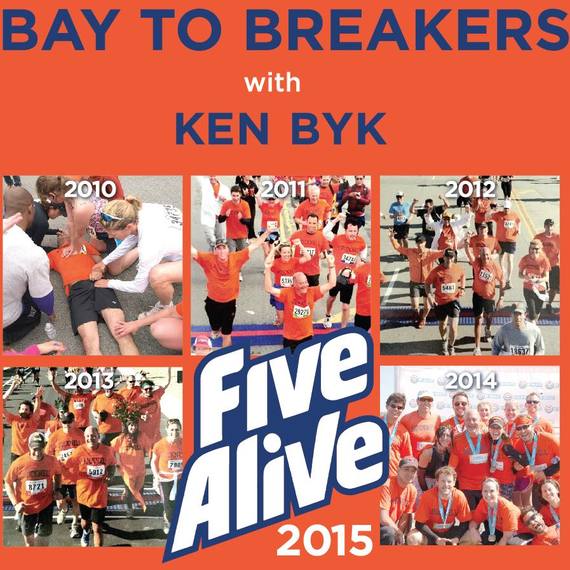

The 2011 Bay to Breakers was the 100th running of the event, which bills itself as "the oldest consecutively run annual footrace in the world," having never changed its course or length since its debut in May 1912.

Byk's return became part of the build-up. He wore another orange Bucknell T-shirt, this time with a picture of people giving him CPR and a note that said, "2010: Not Ken's Best Finish." It also included this quote: "The last time I did this, I died."

In every interview, he mentioned trying to find the woman who'd saved his life. All he knew was that she was an anesthesiologist; he'd even sent a letter to the California Society of Anesthesiologists in hopes that someone there might connect them.

Then he stumbled across the photographer who'd been shooed away by Andy Rodgers.

He mentioned having a series of images that hadn't run in the paper. Among them were probably shots of the woman leading the rescue team.

He checked the next day.

Byk now knew he was looking for the runner in bib No. 34735.

The rest was easy.

***

When Byk called the second time, he had to answer a series of questions to prove it really was him.

"Once he gave me enough details to know it was not a joke, I was ecstatic," she said. "It was definitely one of the happiest days of my life, realizing he had made it."

He laughed and smiled throughout their ensuing conversation. She was bawling. They agreed to meet three days later, and invited media to document the reunion.

That time, she was all laughs and smiles and he did lots of bawling.

"It was an incredibly powerful moment," he said. "I owe my life to this woman. She's my guardian angel."

Now they are running buddies. The last three years, they've run the Bay to Breakers together. (Byk feels bad about this former Olympian slowing to his pace; her teasing reply: "I've got too much invested in you!")

Now they are running buddies. The last three years, they've run the Bay to Breakers together. (Byk feels bad about this former Olympian slowing to his pace; her teasing reply: "I've got too much invested in you!")

They get together more often than that, generally when either is anywhere near the other.

"When we see each other, we break out in big smiles," he said. "There's a unique bond we'll always have."

The experience has changed both of them.

Ruth cherishes their friendship, saying her life is better just because this "incredibly thoughtful, warm and generous" man is now part of it. There's also a spiritual aspect in knowing he was out for so long without a pulse, yet made a complete recovery.

"It made me feel like there was some other forces going on besides just what we were doing," she said. "He obviously had to go someplace for that period of time when he wasn't alive."

As for Byk, he'd already made major changes in his life before his cardiac event, having left the corporate world and buying a small, high-end residential painting company. He's since chilled out even more.

"I have a little stress in my life, but on a 10-point scale, it registers a 1 or a 2," he said. "Whenever anything happens, my reflex is to think `May 16, 2010.' That lets me know nothing else is a big deal. It's a very powerful go-to."

He's also become more devoted to an organization called New Door Ventures, which helps disconnected youth in San Francisco ages 16 to 24 get ready for work and life. And he's become quite a spokesman for the American Heart Association.

***

The American Heart Association helped pioneer CPR over 50 years ago, and continues to refine this lifesaving technique. The organization trains more than 16 million people in CPR, First Aid or Advanced Life Support programs each year in more than 100 countries.

Even without formal training, anyone can be a lifesaver by remembering the steps to Hands-Only CPR -- call 9-1-1, then push hard and fast in the center of the chest, preferably to the beat of the classic disco song, "Stayin' Alive" until help arrives. The AHA also encourages states to pass laws to train high school students in CPR before they graduate, putting more potential lifesavers into our communities.

Nearly 300,000 people die each year because they suffer cardiac arrest outside of a hospital, with 70 percent of those happening at home. A majority of people say they feel helpless to act because they don't know how to administer CPR or it's been too long since they learned.

Since 2008, Congress has designated the first week of June as national CPR & AED Awareness Week. All month, there's added emphasis to teach more people how to become a lifesaver.

Ruth hopes Byk's story illustrates the need to begin chest compressions immediately, and to make sure they're being done deep enough to make a difference -- about 2 inches. She also is a big believer in "keeping going until you are absolutely sure what you're doing is futile."

***

This year's race was just two weeks ago. Byk and his posse were easy to find in their orange Bucknell T-shirts, which have become their calling card.

This year's shirts included a humblebrag across the back: "Five Alive."

"It was my fifth time to cross the finish line since 2010 and it felt equally powerful," he said. "Life is wonderful. That's the strongest feeling.

"Statistically, the likelihood of me being here is in the low single digits. I'm just so grateful, so thankful. I haven't lost sight of that. I'm sure it'll stick with me forever."