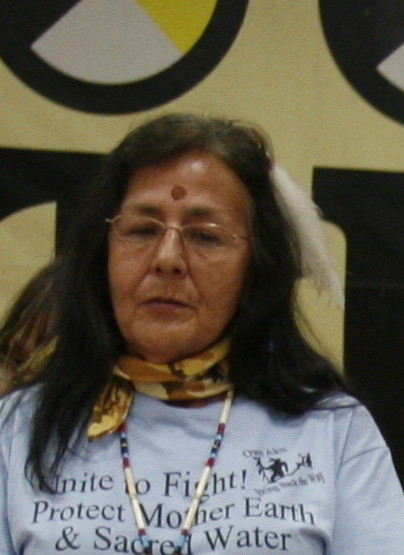

Debra White Plume and Marie Brush Breaker Randall stood in the middle of Highway 44, alongside more than 70 other members of the Oglala Lakota Nation. For hours, they didn't budge -- much to the chagrin of some tractor-trailer drivers bound for the tar sands region of Alberta, Canada.

"This is our land," said Randall, during the blockade in March 2012. "We have to protect" our grandchildren. Randall, then 92, appealed to the truckers attempting to pass through the sovereign territory in Wablee, S.D.: "Please stay out of our nation."

Randall's plea went beyond halting the truck caravan. She and other Native American activists share strong and broad opposition to the development of tar sands, including TransCanada's plan to send Canadian tar sands oil through the Keystone XL pipeline to the U.S. Gulf Coast. The White House final decision on the controversial conduit is expected this summer.

Along the project's path, critics say, lie sacred and sensitive lands and waters that Native tribes rely on -- physically, culturally and spiritually. A growing number of tribes such as the Oglala Lakota are now pledging to stand their ground, fighting Keystone XL in defense of Mother Earth and future generations.

"When this black snake comes through here, there isn't another island for people to go live on," said White Plume, who was arrested for disorderly conduct during the human barricade.

The latest to join the fight in South Dakota are the Yankton Sioux, who vowed this month to block the Keystone XL Pipeline "by all means possible."

Tribal government officials will deliver two resolutions to the State Department hearing on Thursday in Grand Island, Neb. The Yankton resolution attempts to prove ties to the land that would be affected by the pipeline, but that aren't necessarily in the modern boundaries of their reservation. They also renounce a "flawed" process of consultation by the Department of State in its review of the proposed project.

The State Department, in an email to The Huffington Post, said it "has taken the concerns of the tribal nations and other stakeholders into consideration" in preparing its draft environmental impact statement. The department noted that "tribal nations will have additional opportunities to provide input" through the public comment period, ending on April 22, and the department will "take any additional feedback from concerned tribes into consideration."

Jennifer Baker, a Denver-based attorney who practices Indian law, said that consultation is "not happening" to the extent that it should be.

According to its draft review, the State Department consulted hundreds of times with tribes in person and via letter, email and phone. But Baker, who has been working with tribes and communities in South Dakota, said the government-to-government consultations, as required by Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, have been too large, too short and often inaccessible for too many.

"There's no way for them to fully express all of their concerns in the time allotted for a meeting," Baker said.

The "one and only public hearing" for the pipeline is another case in point, Baker told HuffPost while en route to Nebraska for the event. She said she knew many members of tribes who "desperately wanted to attend," but are unable to because of bad weather.

"And these are older folks, elders, who really should be heard," said Baker.

Even Native Americans who attended meetings are "disheartened," Baker added. "They know going in no matter how strongly they feel and how right their position, in the end it has a very small likelihood of having an impact on what's happening."

The pipeline path skirts federal tribal land boundaries in South Dakota, Baker said, yet will still cut "almost through the heart" of a large protion of the land set aside for exclusive use by tribal nations, as recognized by the 1851 and 1868 Laramie Treaties. The pipe would cross native spiritual sites, burial grounds, hunting lands and sources of drinking water, including the Mni Wiconi pipeline, which transports water to the Oglala Lakota from the Missouri River.

"There are so many bodies of water that this will cross," said Baker. "And it's absolutely inevitable that a spill will happen. It's just a matter of when and where."

Baker emphasized the at-risk locations: "The pipeline goes through a lot of indigenous, minority and low-income communities. They are the least equipped to handle something like that, yet ones most at risk." What's more, Baker said, a spill would "destroy access to crucial components of their spirituality. That's not something that can be cleaned up and given back."

TransCanada spokesman, Shawn Howard said in a statement to HuffPost that the company has "made a reasonable and good-faith effort to identify tribes that may attach religious and cultural significance to historic properties that may be affected by the undertaking, even if those tribes are located a great distance away from the project."

Howard said that TransCanada has also been "actively working with tribes in exploring employment and business opportunities for both the construction and operations phases of the project."

White Plume said her people also have a name for corporations like TransCanada that are set to get rich off tar sands: "fat takers."

"The threat to our drinking water is so enormous that any number of jobs, any kind of economic development, would be irrelevant when our water is contaminated without the possibility of being cleaned up," said White Plume.

Despite assertions from TransCanada and the State Department, White Plume said that the "points of consideration" for her people have "not been considered."

The Oglala Lakota recently passed its own legislation opposing the pipeline, which brought out the activists -- including another elder in a wheelchair -- to Highway 44 that sunny day last year.

Near a child holding a "Stop the Pipeline" sign stood White Plume wrapped in a banner that read, "Sacred Red Earth."

"The Mother Earth Accord has a moratorium on tar sands development. These are connected with tar sands development," she told the drivers, referencing their trucks. "You can't violate our laws to please a corporation or to please the state of South Dakota. Our laws are important."

White Plume has been helping to train her people for future peaceful protests through a program called Mocassins on the Ground.

Should President Barack Obama ultimately decide to approve Keystone XL, White Plume said the tribes will be ready: "The communities will be able to stand their ground and say 'no' even though he has said 'yes.'"

"Obama has to realize he has 94-year-old grandmas and 10-year-old boys willing to risk arrest, do whatever has to be done to stop TransCanada from coming on our land," White Plume added. "Who is he standing for -- people or corporations?"

"Indians say no," said Randall. "This Indian momma says no."

Part of a series on people living along the proposed path of Keystone XL.