Most Americans are familiar with the adage that 11 o'clock on Sunday morning is the week's most segregated hour. Although there is less homogeneity in American churches than when the observation was first popularized in the 1950s, the segregation of Christian worship continues to be analyzed by sociologists and lamented by religious leaders. The perpetuation of racial separation on Sunday mornings may be due to preference, convenience and a highly segmented religious marketplace. But its historical origins are to be found in white desires for segregated congregations.

The most concerted effort to challenge church segregation was launched during the first half of the 1960s, when the same young people who were integrating lunch counters, parks and libraries took aim at white churches. "Kneel-ins," as they became known, were visits by small groups of blacks (often accompanied by sympathetic whites) to prominent white churches in towns and cities across the South. The first kneel-ins took place in Atlanta in August 1960, and they spread throughout the region over the next six years. Kneel-ins were not staged to protest unjust laws, but to test white churches' tolerance for integrated worship. They were intended to illuminate the moral dimensions of segregation by creating compelling spectacles of exclusion or embrace.

As important as they were to the people who engaged in them and endured them, kneel-ins have somehow fallen through the sifting bowl of history. The black church's importance as a venue for organizing and inspiring the soldiers of the civil rights movement is well-attested; but the role of the white church as a moral battle ground has been largely overlooked. It is vividly remembered, however, by many of those who experienced kneel-ins first hand. Particularly in places where racial division and alienation remain prominent features of the social landscape, contested memories of church visitation campaigns linger half a century later.

In Memphis, for instance, where kneel-in campaigns erupted in 1960 and 1964, many recall what they saw and felt when black and racially mixed groups dared to visit white churches. Among them are the black students from LeMoyne College (now LeMoyne Owen) who in August 1960 sought to integrate an outdoor youth rally sponsored by the First Assembly of God. Although rally organizers had advertised the rally as being "open to all," the black young people who attended were arrested and charged with felonious disturbance of a religious assembly. Thus began a five-year legal odyssey which included appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court and ended when the students' convictions were commuted by the governor. In the meantime, college graduations were delayed and careers were put on hold.

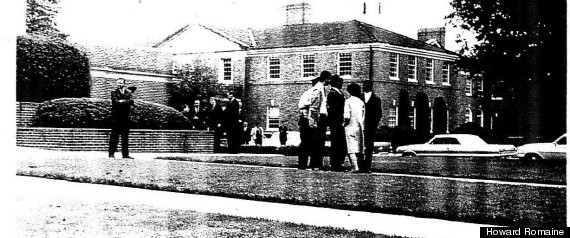

The 1964 Memphis kneel-ins were conducted by members of the intercollegiate chapter of the local NAACP who had been trained in non-violent protest by James M. Lawson, Jr. Students in interracial pairs visited prominent churches, most of which were willing to admit, if not welcome them. But after two students were turned away from Second Presbyterian Church on Palm Sunday, there began a full-fledged kneel-in campaign that brought the church national media attention and divided its membership. When denominational sanctions came down upon the congregation, the clergy joined younger members in a revolt against senior elders who were rotated out of service and soon departed to form their own church.

Among those who remember the kneel-in crisis at Second Presbyterian are former deacons who were recruited to guard the church doors, student visitors (white and black) who were subjected to considerable pressure by church representatives, and children of the congregation (now in their 60s and 70s), many of whom were traumatized by what they saw taking place in front of their church. And, of course, the institution suffered trauma as well. Healing has come through a gradual process of addressing the kneel-ins' legacy of exclusion with apologies to African Americans who were kept out of the church in 1964-65 and an ongoing commitment to urban ministry and racial reconciliation in Memphis.

Independent Presbyterian Church, the congregation founded on a segregated basis by those who broke away from Second in the wake of the kneel-in crisis, has only recently begun to deal with its own complicated racial history. In 2010, after 45 years of downplaying or denying its racist origins, a sermon attacking the supposed biblical injunction against interracial marriage stirred so much controversy that the pastor resigned and the church began to engage its history in a process of "prayer and corporate repentance." It has been noted that if the American civil rights movement had led to a South Africa-style process of "truth and reconciliation," race relations today would look very different. Perhaps, in the absence of a grand scheme of reconciliation, healing will be found in the local practices of truth-telling and repentance that have become one the legacies of the kneel-in movement.

Stephen R. Haynes is the author of 'The Last Segregated Hour: The Memphis Kneel-Ins and the Campaign for Southern Church Desegregation.'