Stanley didn't travel. His work and life were intertwined and based entirely in England, so the world came to him. This was both a benefit and a complicating factor as I set about strategizing publicity for A Clockwork Orange, which was set to have its world premiere in New York on December 19,1971.

There was a limit to how much Stanley would do to publicize a film -- by preference and design. He wanted his words to have meaning, which meant that interviews had to be consequential. Further, he insisted on having the right to edit his direct quotes until he felt they accurately represented what he wanted to say. They would be a permanent record that had to stand the test of time. Immediate answers, without subsequent consideration, could be interpreted in ways that would diminish their substance. He could spend days "cleaning them up" before he was satisfied. As a result, they have a rare lucidity.

Broadcast was out of the question. With radio and television interviews, it was impossible to exercise the control he required. And there was little chance to weigh in with meaty responses or have an extended, meaningful dialogue. In most cases, doing broadcast interviews also meant traveling to someone else's studio -- a waste of time.

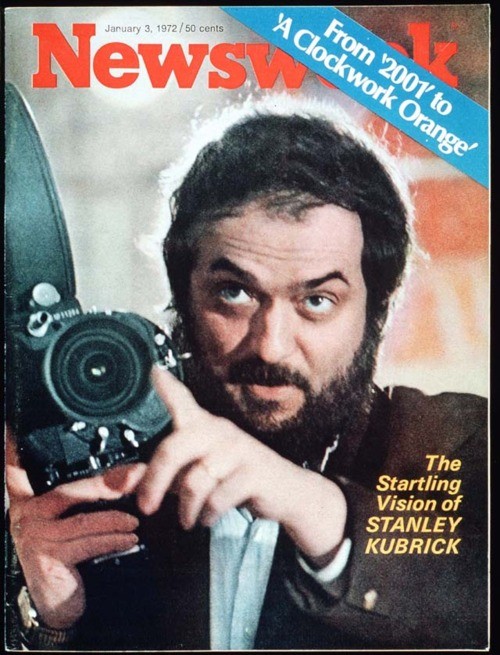

A key part of our strategy was to secure the cover of one of America's two major mainstream news magazines, Time and Newsweek. Unfortunately, Time had instituted a policy of not running cover stories on film directors, as their last one, on Ingmar Bergman, hadn't sold well. Instead, Time critic Jay Cocks would write an inside story and extended review for the film's opening week.

That left Newsweek, whose editors jumped at the chance to publish the first piece on the new Kubrick film. Paul Zimmerman, Newsweek's film critic, flew to London three weeks before the opening and viewed A Clockwork Orange several times. Stanley was a great conversationalist and loved to be stimulated and prodded about his work. They were locked together for hours at a stretch, and when Paul, who later wrote the screenplay for The King of Comedy (1983), left at the end of the week, exuberant from the encounter, the cover seemed a certainty.

Then, ten days before publication, I received a message from a new name at Newsweek. Problems? Cultural stories could always be bumped for breaking news, and I thought of how morose my colleague Dick Winters had looked back in 1965, when, after he'd spent a year nurturing a Dr. Zhivago cover at Time, the magazine bumped his baby to report the news of NASA's first manned space rendezvous. The unpublished Zhivago cover remained forever framed in his office.

Thankfully, we were not in danger of being displaced. Newsweek's art director was calling to coordinate Stanley's photo shoot. There was a two-day window. Great. No problem.

I was overloaded with last-minute deadlines and was preparing for an imminent trip to New York. But before running through our evening checklist, I wanted to confirm a time for the Newsweek shoot. Stanley didn't look up from his desk, "Tell them I'll take the picture. And I'll need their specs." I was stunned. "Stanley, this is the cover," I said. "They have their photographer; you have photo approval."

There would be no budging. "I'll take the photograph," he said. "Find out when they need the negatives in New York."

Stanley was an ace photographer. He intended to set a precedent by shooting his own cover portrait, controlling the image he wanted to project.

The next conversation with Newsweek's art director had me reiterating how Stanley knew more about photography than anyone; how he developed his reputation as a photographer for Look; how there would be a selection of choices. Not to worry, I assured him. You know he's a technical genius.

He replied with an ultimatum: "This is unheard of. We take our own cover photographs. If he won't be photographed by Newsweek, he won't be on the cover."

Was this actually happening? Losing our major break over the cover shot?

We were five hours ahead of New York, which gave me a time advantage. I called Paul Zimmermann at home. He offered some comfort. "They're not going to lose the story. I'll see how things stand in the morning."

Stanley was playing the odds. Without a war starting, they were locked into the story; Newsweek had the exclusive and too much time and effort had been invested.

The phone rang. It was Stanley with an afterthought. "Give him these specs. He'll know what I'm doing. You'll get through it."

In the morning came the reluctant call from the art director, curtly asking for directions to Abbot's Mead for their courier.

"These better be good." He hung up.

At 10 o'clock that evening, Stanley began setting up the shot in the painting studio of his wife, Christiane. Executive producer Jan Harlan was there to assist. Stanley held out until the last possible minute to ensure there would be no alternative to using his shot. I wouldn't leave until the film was given to the waiting courier.

Stanley moved the lights and placed Jan on a stool in various positions as he looked thought the lens for the angle he wanted. Jan pointed his finger as Stanley directed. Then Stanley gave him the camera he'd chosen for a prop.

After an hour of adjustments, Stanley changed places with Jan after showing him where to press the button for the shot. Nothing moved. Jan pressed continually as the roll of film progressed. Stanley looked toward the camera, pointing out, just as he'd instructed Jan.

The credit for the January 3, 1972, issue of Newsweek reads:

Cover Photograph: Stanley Kubrick.

This is the third in a series of reminiscences about Stanley Kubrick written by Mike Kaplan, a veteran film executive who was Kubrick's marketing man for his film 'A Clockwork Orange,' having also worked extensively on the release of 'Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey.' Previous installments can be found here and here. 'A Clockwork Orange' opened nationally 40 years ago this month.