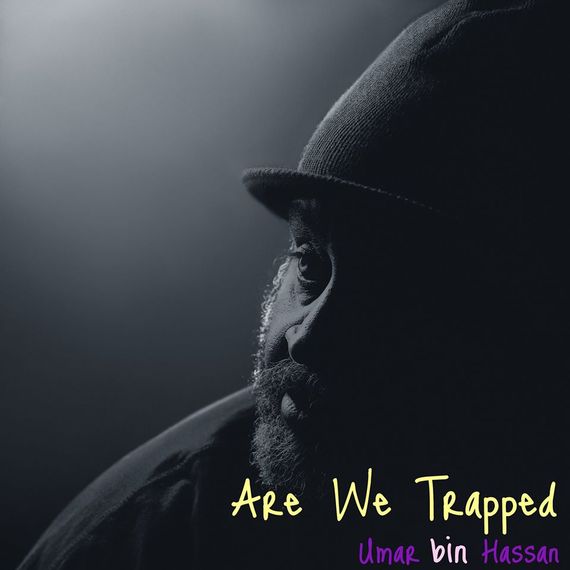

Forty-five years after the first Last Poets recording, Umar Bin Hassan is still coughing up truth-telling gravitas. His latest CD, Are We Trapped, tracks his personal journey and extends his word magic over ready beats. Featuring guest emcees stic.man, from dead prez; Styles P, from The Lox, and Stetsasonic's Daddy-O, the set also makes room for trumpeter Roy Hargrove, late guitarist Michael Campbell (Change, D'Angelo) and German drummer Brixx. "I'm rappin' again," says Bin Hassan. "I'm just really happy to be here."

Credit: Natasha Kertes

Bin Hassan grew up determined to not follow in his family's footsteps, working in the local rubber mill. In January, 1969 he escaped his Akron, Ohio hometown, pawning his sister's record player for $25, and purchasing a $15 bus ticket. He boarded a New York-bound Greyhound and arrived in the Big Apple with twenty-two cents, a pair of jeans in a brown-paper bag, and the dream of joining The Last Poets.

He first encountered members of The Last Poets in 1968, before they went on stage at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where he was head of security. "The Poets were giving a performance and I'd just left the streets hustling, trading in my beaver skins and Gators for khakis, a kufi and combat boots," he remembers. "Abiodune comes up to the security desk: 'I'm one of the Last Poets. I ain't gotta get checked!' At the time I was strapped, and I just pulled up my jacket, showed him my two pistols and told him, 'Listen, brother, you need to check in before you check out!'"

Beyond friction at the gate, the show's fiery mix of poetry and percussion inspired Bin Hassan, who was gaining a neighborhood rep for fighting the power. "They just knocked me out the box," he says of the Poets. "Afterwards, me and Dune talked. He finally told me, 'Look, if you ever decide to come to New York, stop by our loft in Harlem.'"

When Bin Hassan finally made it Uptown, he emerged from the subway, onto the bristling 125th Street corner where the brothers' loft was located. He says, "I had never seen so many black people in my life!"

Weeks later, he was part of the iconic spoken-word group, the only voice voted in by "the people." As Bin Hassan tells it, a university-age New York City crowd deemed him deserving when, answering a challenge, he dropped an impromptu lyrical bomb titled "Motherfucker." So lethal was this decapitating strike, it hasn't been heard in public since.

With Abiodune Oyewole, Jalaluddin Mansur Nuriddin and Bin Hassan as its core (along with conga drummer Elijah Muhammad), the group's 1970 debut, The Last Poets, soared into the Billboard magazine Top 10 and quickly sold gold. It became known for mighty musical op-eds like "Niggers Are Scared of Revolution" and "When The Revolution Comes." A year later the follow-up, This Is Madness, also became a classic.

The influence of The Last Poets can be heard in the vanguard of today's hip-hop. In 2005, Bin Hassan was featured on Common and Kanye West's hard-rocking "The Corner." And just listen to the syncopated swing and slam-poetry flow of "Ain't Free," from Kendrick Lamar's To Pimp A Butterfly, or D'Angelo's "The Charade" and the Common/John Legend collabo "Glory," both of which bring Last Poets-style protest music back to the mainstream!

Daddy-O, Umar Bin Hassan and Will Roberson in the studio

The new album, overseen by Will Roberson for his Diggin' 4 Brown imprint, was in the works for several years. Shortly after its conception the financial collapse happened; then producer Roberson's ex-wife, Luciana Rochford (the muse for Diggin 4 Brown), committed suicide (actress Lindsay Lohan has expressed interest in the feature-length screenplay, Luciana, about Roberson and Rochford's story).

"I would get calls from Umar from time to time, about why I haven't released the music," says Roberson. "Sometimes they were not very nice calls, but after everything I went through, I wasn't gonna put the music out at the wrong time."

On the third anniversary of Luciana's death, Bin Hassan visited Roberson. "We sat and talked about our journey," Roberson remembers. "We had a drink in Luciana's honor and recalled good memories. When Umar left my house that night, I felt like it was a good time to release the music."

The poem "White Girls" started out as a dedication to Rochford, who Bin Hassan credits as being "a big part" of the new project's development. "Blow" recalls the downward spiral that resulted from Bin Hassan's addiction to crack cocaine ("I went from champagne and freebase to crack and Olde English"), and the title track is a song of hope for children that are given no direction. "Nobody's looking out for then, " says Bin Hassan.

New York City, which nurtured Bin Hassan for decades, and where he connected with intellectuals, musicians and others interested in art, radical politics and history, also nearly killed him. The demon of drug abuse took hold hard. These days, he lives in Baltimore, clean and helping to raise his grandson, who inspired the poem "The Verge."

"I'm talking about the future of America in that one," he explains. "This young generation is reaching out among each other much more than we did. The whole racism thing is not really lingering on them. Actually, they're trying to get out from under it as much as they possibly can."