Being a conductor is, by definition, a follow-the-leader business. But just because people are supposed to follow you, even paid to follow you, doesn't necessarily mean they will. Or, if they do, that they'll do so happily.

This I know only too well from my years as a cellist in the orchestra pit, where conductors are sometimes seen as necessary evils. (Common orchestral musician joke: "Q: What's the difference between a conductor and a bull? A: On a bull, the horns are placed up front and the asshole is in the back." Symphony professionals can be a coarse lot.)

Among orchestral musicians there is a favorite story about Fritz Reiner, the brilliant maestro and stern taskmaster of the Chicago Symphony.

Reiner was famous for his tiny, hyper-controlled conducting movements, which represented more or less the opposite of the more dramatic, grand-gesture Leonard Bernstein school. When critics noted that the range of motion of his baton tip could be contained in an area the size of a postage stamp, they were only slightly exaggerating.

One day, as a joke, a double bass player brought a pair of binoculars in to rehearsal. As Reiner began conducting, the bass player raised his binoculars and peered through them at the maestro. Without missing a beat (literally), Reiner continued conducting with his left hand while with his right, he scribbled a hasty note and held it up so the bass player could read it.

It read, "You're fired."

That's one leadership style. My father had a different one.

For fourteen years, my father conducted one of the country's leading amateur Bach choirs in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. For a few of those years, I played in the orchestra and had the opportunity to watch his work up close.

My father's voice was so soft it was often hard to hear in normal conversation, and on a crowded stage, practically impossible. Yet I noticed that when he spoke during rehearsals, not a single musician ever missed a word. Why not? Because when he began speaking, they would grow so quiet a dropped pin would have sounded like the cannonfire in the 1812 Overture.

He would speak -- and everyone would lean in, craning to hear his every word.

He pulled them in.

I saw the most cynical, don't-tell-me New York union musicians turn into putty when my father made a suggestion to start this passage with an up-bow, or to take that passage sotto voce so we could more clearly hear the tenors. People would turn themselves inside out to follow him -- and they would follow him anywhere.

There were two reasons for this. First was that he was superb at what he did. He knew this music inside and out; it was in his bones; it was his life.

And second? He treated them with absolute respect. He didn't tell them what to do; he collaborated with them.

That is another leadership style altogether.

It's something like the difference between pushing and pulling.

Take an ordinary window fan and place it in a window, blowing inward. Switch it on. How far can you push a column of air into the room? Not far: within a few feet it starts doubling back on itself. But now, reverse the fan's position so that it is blowing out -- and you can pull that column of air all the way from a single open window clear on the other side of the house, even hundreds of feet away.

There is leadership that pushes. And there is leadership that pulls.

How far can you push people? Only so far. How far can you pull them? An awfully long way, if your leadership style embraces total respect for those you lead as its foundation.

When that second kind of leadership speaks -- even when in a voice as soft as my father's -- people listen, because they feel valued, and because of that, they trust.

That kind of leadership, we'll follow anywhere.

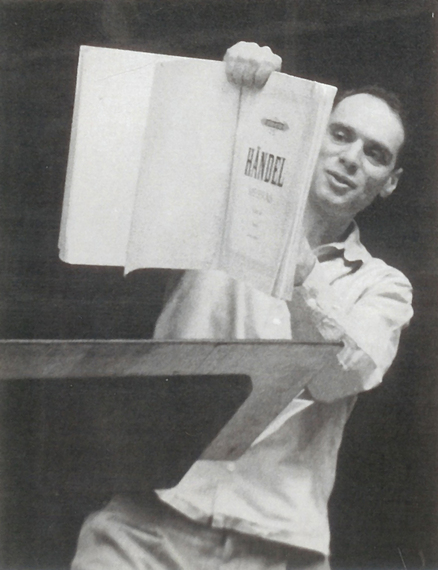

Photo: Alfred Mann in a rehearsal of Handel's Messiah at Carnegie Hall in 1959, pointing out a passage from his Messiah edition to orchestra members.