We are all one, and if we don't know it, we will learn it the hard way. - Bayard Rustin

A few days have passed since the Ferguson non-indictment, making clear how much past is not even past. I think about Bayard Rustin, and how he would advise all of us right now.

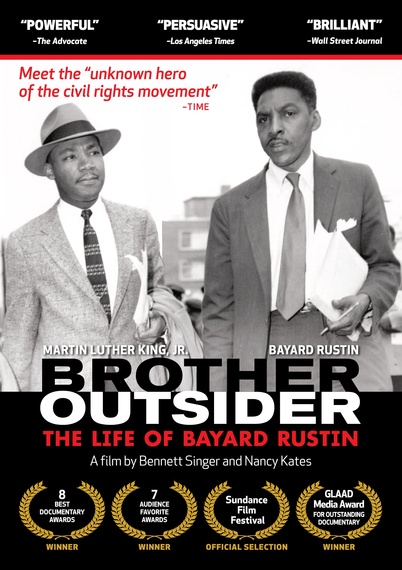

Let me ask: are you thinking Rustin who? If you are, that's OK. That would have been me, too, until recently. I am embarrassed to say that only once I learned of the documentary Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin, did I learn of the human rights titan and his central role in the American civil rights struggle.

While Rustin spent decades fighting for peace and for economic justice, I'd argue that all of us should know 1) Rustin convinced Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to embrace Gandhian nonviolence; 2) Rustin was the powerhouse director of the 1963 March on Washington; and 3) because Rustin was gay, and unwilling to deny this central part of his being, he lived with fears and discrimination that oft-threatened his ability to protest and organize to the best of his ability. For too many years, adversaries could use publicity of a previous arrest on a "morals" charge as blackmail.

But if Rustin was afraid or daunted, he never showed it. He kept living his life, standing up for anyone who needed a voice. He loved Black people, but as evidenced by his global activism, he loved all people.

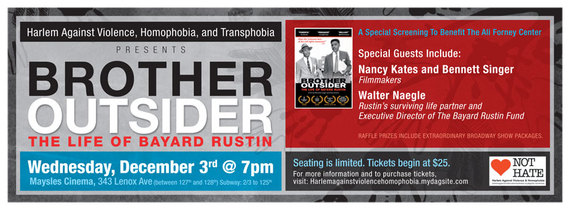

Because of Rustin's mighty example, our organization of Harlem neighbors have chosen to screen Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin on Dec. 3 at Maysles Cinema. Together we will honor and learn from the life of this once-Harlem resident. A post-screening Q&A will feature filmmakers Nancy Kates and Bennett Singer, longtime partner Walter Naegle, Harlem historian and activist Michael Henry Adams, Harlem LGBTQ activist Jennifer Louise Lopez, and moderated by playwright and activist Joan Lipkin. All monies raised go to the Ali Forney Center, a Harlem-based nonprofit that helps homeless LGBTQ youth.

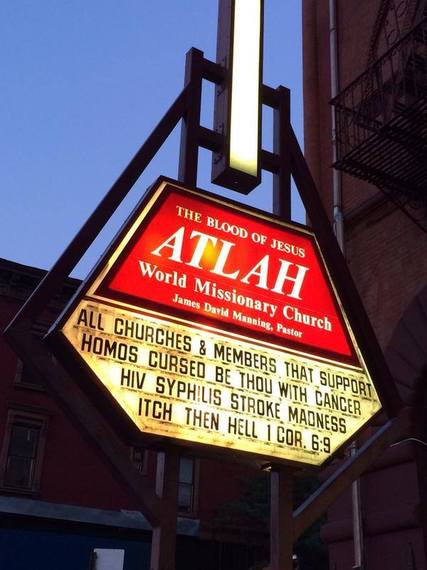

Why are we doing this? We are neighbors and friends united under the banner Harlem Against Violence, Homophobia, and Transphobia. We formed to resist the hate speech constantly displayed by ATLAH Missionary Church on 123rd and Lenox. For several years, they posted hateful messages towards President Barack Obama. But once they posted "Jesus Would Stone Homos" the speech was not only hateful, it was murderous--yet somehow was considered "protected" speech. We decided that instead of picketing, we would raise money for the people who are often most vulnerable to this kind of hurtful religious-based rejection--homeless LGBTQ youth. ATLAH hasn't stopped posting hateful messages. We haven't stopped resisting. So far, we have raised $15,605.

I am grateful to filmmakers Nancy Kates and Bennett Singer for sharing Bayard Rustin's profound life story in such a powerful way, and for being willing to allow us to screen the film for our fundraiser. Brother Outsider is the winner of eight best documentary awards and seven audience favorite awards. The film also won a GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Documentary. You really want to see this film! For more about our Harlem work and fundraising, and to buy tickets to the Wed. Dec. 3 event (including incredible Broadway tickets that include backstage cast visits, courtesy of director and Harlem resident Scott Ellis) please visit our site.

Co-producer and director Bennett Singer was kind enough to submit to an interview with me, and share more about the experience of creating Brother

Outsider.

Interview with Filmmaker Bennett Singer

When did you first learn of Mr. Rustin and his work?

It was back in 1986. I had just graduated from college and had an internship at Blackside, Inc., the company that produced Eyes on the Prize (the landmark PBS series on civil rights history). One of my first tasks was to do research on the 1963 March on Washington, which Rustin organized. I had never heard of Rustin before this--but the more I read about him, the more I felt as if I had opened up a novel and met a larger-than-life character. He made such a major difference in so many movements--bringing Gandhi's tactics of nonviolence from India to America; becoming a mentor to Martin Luther King Jr.; and playing a key role in shaping the strategy and vision of the civil rights movement. And while he was doing all this, he refused to hide or apologize for his identity as a gay man.

How did you decide to make a film about Bayard Rustin?

My college friend Nancy Kates called me in 1997. She had recently gotten her Master's from the documentary program at Stanford, and she had read a book review of the first biography of Rustin, Jervis Anderson's Troubles I've Seen. Nancy asked what I thought about the idea of making a film on Rustin. I told her it was a fantastic idea, and we teamed up as co-directors. It took us five years, but we managed to get it done!

Tell us about the process of creating this documentary. Did you have any unforeseen challenges? Any great surprises--good or bad?

When we started, the big question was whether we could find enough footage to tell Rustin's story. Our researchers literally scoured the globe for images, and we wound up with material from about 100 archives in Africa, India, Europe, Canada and the U.S.--including footage of Rustin playing football as a high school student in West Chester, Pennsylvania, circa 1929! We were also really fortunate that Rustin, who was a music major in college, recorded two albums of spirituals (available on CD at www.rustin.org). We used his singing extensively in the film, and the lyrics of songs like "Scandalize My Name" and "Lonesome Valley" have an uncanny way of telling his story. His singing is incredibly poignant.

If you could ensure that Americans knew one thing about Bayard Rustin, what would it be?

For decades, Rustin has been in the shadows, erased from history in large part because of his openness and honesty about being gay. But just last year, in 2013, Rustin received a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom--the highest honor a civilian can receive in the U.S. In presenting this award, President Obama described Rustin as "an unyielding activist for civil rights, dignity, and equality for all [who] fought tirelessly for marginalized communities at home and abroad. As an openly gay African American, Mr. Rustin stood at the intersection of several of the fights for equal rights." It's so heartening to see Rustin being recognized -- and to see the intersectionality that was at the heart of his life acknowledged as part of this recognition.

Are there any words or images from the film, or your research, that particularly stick with you?

Before his death in 1987, Rustin requested his FBI surveillance file under the Freedom of Information Act. About 10,000 pages arrived on his doorstep, and his life partner Walter Naegle, who appears in the film and was invaluable to the project, shared the entire file with us. We quote it throughout Brother Outsider to remind people that from the official point of view of the federal government, Rustin -- and the entire civil rights movement -- was seen as subversive and un-American. The FBI repeatedly referred to Rustin as a "known sexual pervert." I also think it's chilling to consider the kind of surveillance that was conducted on Rustin -- in which the government wiretaps and monitors a citizen who is not accused of any specific crime -- in light of the revelations that Edward Snowden made about surveillance taking place today.

As we cope with different forms of oppression and repression in 2014 America, what guidance do you think we should take from Bayard Rustin's life work?

"We are all one," says Rustin at the end of the film. Then he adds: "And if we don't know it, we will learn it the hard way." That insight about our interconnectedness was at the center of Rustin's worldview and guided all his work. It stems from his Quaker upbringing and was reinforced by the lessons he learned around the globe as an international human rights activist. And it's profoundly relevant today.

Why did you choose to work with Harlem Against Violence, Homophobia, and Transphobia?

Throughout his six decades as an activist, Rustin encountered hate and violence and racism and homophobia on a regular basis. Some of the resistance he faced came from segregationists; but some of it came from folks within the civil rights community. He was fearless in confronting his opponents and always sought to use the power of nonviolence and love to overcome prejudice and injustice. His story inspires me every single day, and I hope it will inspire activists and citizens who are working to combat fear and hatred in Harlem -- and in other places, like Ferguson, that are wracked by conflict and polarization. Like Dr. King, Rustin wasn't out to defeat his opponents; his goal was to find common ground based on our shared humanity, on the idea that "we are all one."