David Flores is a Social Studies teacher at YouthBuild Charter School of California's LA CAUSA East Los Angeles campus. YouthBuild serves students ages 16-24 who have left traditional high schools without a diploma. David spoke about his ideas for supporting educators and students at a recent TEDxYouthBuildCharter School event titled, "Radically Rethinking Public Education."

Here David talks with Learning Los Angeles about how his own life has informed his beliefs about how we need to support educators and students...

David, what do you hope we learned from your presentation?

In framing the talk, I sought to challenge a few common misperceptions. First, I serve pushouts not dropouts. Second, I serve students "placed at-risk" not at-risk students. Third, effective teaching is connected to educators' environments. I wanted to create a paradigm shift for how we understand the issues in hope of rethinking solutions.

For example, in challenging the power of labels, I wanted the audience to consider how the "dropout" label unfairly blames students as being solely responsible for their situation. I began the TEDx by telling a story of a question once once asked by a student, "Would you want your own child to be in a program like this?" I recognized the dilemma of answering this question. If I said "No", students would think that I was accusing them of being dropouts, adding another layer of stigma to how they perceive themselves. If I answered "Yes", they could interpret my response as meaning I would be fine if my own child dropped out, since they think of themselves as dropouts. This interesting conversation.taught me that our students want authentic relationships with their teachers.

Students were surprised when I told them I would be fine if my child were in a program like LA CAUSA. Why? He would be with a team of educators like myself - committed to the well-being of young people. Students must know they have somebody who cares about them. Relationship is the root of learning. If students feel we care, they feel connected to the program and to us. Then they are willing to be held accountable and hold us accountable for their learning.

I wanted this story to compel people not to think of our students as dropout but as push-outs, and not of as "at-risk" but as being "placed at-risk." As push-outs they are not completely responsible for leaving traditional high school, because traditional high school, along with other societal factors, placed them at risk of being pushed-out in the first place. So I figured, if my students were able to understand this shift in thinking when I explained my response to the question, I should frame my talk around this paradigm of push-outs, not dropouts.

David, far right, at the TEDx event. "We constantly have this conversation about pulling yourself up by your bootstraps when we know it takes a village."

How much do you share about your own life?

Students know I grew up in foster care, I was raised by an African-American family, and that I was shot when I was nineteen. They know I spent a year in jail, and after jail I made it to UCLA. I share that story with them because I remember being their age in a similar environment, and needing to know somebody out there who overcame those challenges. That person didn't exist for me. That lack of a role model caused me as a teenager to go the route I went. As I teach, I'm very aware of what I needed as student, and I assume that's what our students need. Then I work towards addressing those needs through the content and our relationship. A lot of our students have been homeless, are on probation or parole, and are parents. These students may feel a sense of hopelessness. So, I share to hopefully inspire. Hope is powerful, especially when that hope is based on knowing that somebody else has made it despite the struggle.

How did you turn your life around?

Key people turned it around for me after I was kicked out of Washington Prep and transferred to Crenshaw High School. Things changed due to the caring nature of one teacher, Florence Avognon, who is now my mentor teacher. She's a "turnaround" person in my life. She was the first person who didn't assume that I simply identified with Latino culture, but understood that I identified with African-American culture. She was the first person to get to know me and support me by explaining to my peers that I was normal. She helped us understand that our identity isn't inherent in our biological makeup, but is taught through our culture. So who I was reflected what I had learned growing up. She was the first teacher to take time to get to know me as a person first. She helped me understand myself.

You spent time in jail. How were you able to get a teaching credential?

It all began with education. After being released from jail, the conditions of my probation required me to enroll in school, and to maintain a "B" average. After being released, a family invited me to live with them. So I relocated, went back to school, maintained a B average. A year and a half after jail, I transferred to UCLA, and three years later graduated with honors. After graduating, I returned to court and asked the judge to reduce my felony conviction to a misdemeanor. Impressed with my accomplishments, the judge did more by expunging my record. After deciding to teach, I applied to graduate school for a Masters in Education and a teaching credential at UCLA. Part of the certification process required me to write the state a letter explaining what happened and what I had done to prove my worthiness to teach. In my letter, I quoted from the Brown v. Board of Education decision, that education "is the very foundation of good citizenship." So my letter attempted to challenge the decision makers to honor this value and help me to produce good citizens through allowing me to teach.

What do you see as the crucial job for teachers?

To be advocates for students and other educators in this era of supposed education reform. We must talk about how to position students for success. We must be deliberate about creating environments that allow students to thrive and contribute to themselves, their families, their communities. To allow students to experience their full potential, an educator has to be in the same type of supportive environment. Instead, teachers are being blamed for students' shortcomings. Young people come to us deficient in skills. We must advocate that we are doing our jobs when we move a high school student from reading at the second grade to the sixth grade level in nine months. Unfortunately, in this reform climate we're still blamed because he's not reading at the high school level.

Teachers must also do a better job of advocating for effective teaching environments. In order for us to do well, we have to be in environments where leadership, whether CEO, principal or Executive Director, supports us. We feel supported when we are provided quality professional developments. We are positioned for success when we have access to updated technology. An effective teaching environment is a supportive environment.

Currently teachers are being asked to do more with less. If we're teaching not four, but seven different classes, it's hard to be effective. We can't reteach, master content, and improve our skills. We have to ask ourselves, "Are we really helping students by having teachers do so much?" If the answer is "No," then teachers need to push for honest conversations about how leadership can provide that support.

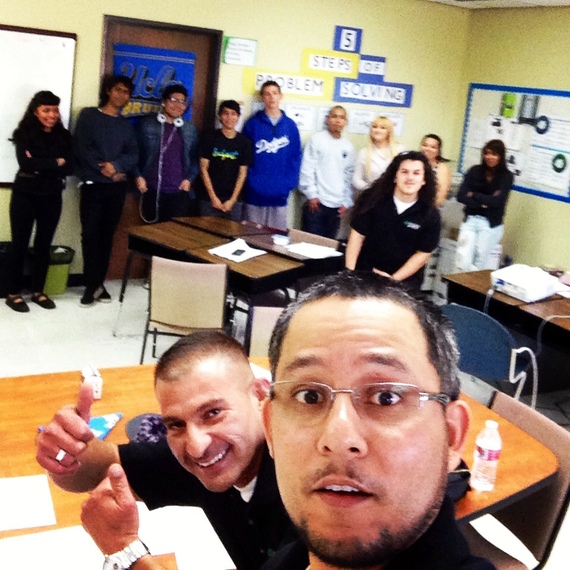

David with students. "They realize that as lower-working class students, they're not even in the conversation."

What do you feel is effective at YouthBuild?

At YouthBuild Charter, our approach to education is authentic. Let me give an example. In Government class, I teach a unit on gun rights. I deconstruct the history of second amendment. I begin the unit with an experiential activity. Students watch the first twenty minutes of Batman The Dark Knight Rises. I stop the film at the moment of the shootout in Colorado and play audio clips of the 911 calls, followed video clips of the interviews and other clips attempting to break down the mindset of the shooter. Then we move into personal experience - who's been a victim of gun violence, or knows someone who has. We look at the Isla Vista shootings and start to break down the father's talk about the NRA. Students design projects that demonstrate their understanding of the second amendment and recurring controversy. Teaching this way requires staying up to date on current events and adapting it to what's happening in the nation, our neighborhoods, and the world.

Is there a particular student who sticks with you?

Mark de la Torre reminds me of my best friend growing up. Mark's a very determined young man. He's often here before the teachers. He's rarely absent. He came in last year and struggled academically, but he was dedicated. He takes a lot of pride in being on time. That's key, something as simple as being punctual resulted in his transformation as a student and leader. I think his transformation began when he went to our 3D (Decisions Determine Destiny) men's leadership retreat, and started to realize he had a voice that people wanted to hear. Since then, he joined our Youth Policy Council. He's come a long way in two years. We've witnessed him engage, and go to Sacramento and DC to advocate on behalf of students and teachers. That's what I want all my students to realize is in them. He's a tremendous young man.

Do you have ideas to share with educators?

We need to help students understand their positions in society. We need to hear their voices. They're sharp. We listened to President Obama's State Of the Union address in January, and a student asked me, "Why isn't he saying anything about us, he keeps talking about the middle class." At that moment I realized, "I guess I'm doing my job. They recognize that as lower-working class students they are not even in the conversation." That was a powerful moment for me, that students could initiate a conversation about their own voices. Those in power need to seek students' voices. Their policies don't reflect what these students need.

What do these students need?

Support. Our students come from communities, families, and schools that don't meet their basic needs. We're supposed to fill that need, but we don't have that support, either. How can I prep my students for 21st century jobs when I don't have computers! How am I supposed to do that? Until a few months ago, we didn't even have a lunch program. When students don't have shelter, how are we supposed to help them believe in what's possible? They don't have the basics they need to achieve the American Dream. That's the story not being told. These students are talented and smart but struggle because their American Reality has made it hard for them to dream about the Dream. We constantly have this conversation about pulling yourself up by your bootstraps when we know it takes a village.

A lot of our young people need the most basic support, and we don't want to have this honest conversation. We need to talk about how the school systems fail students. Like, by having long-term substitute teachers in math classes who can't teach the material. Instead, we blame the students and accuse them of being the reason they fail and dropout and are at-risk. We need to look at ourselves and at the institutions that place students at-risk. We blame the most vulnerable people in society for their shortcomings instead of really looking at the institutions and adults in their lives. Adults don't hold themselves accountable. We blame students, and they internalize that blame by blaming themselves. I tell them, "If you had been in an environment that made learning exciting and fun, you would have wanted to be there, and you would have succeeded." That's what we don't provide. These young people might as well be invisible.

I would love to see the day when we could just be honest and ask, "How can we change this situation?" But we don't, and these young people just keep coming to us and coming to us. Larry, my student, shared an insight in Economics class, questioning whether he wanted to achieve the American Dream. He said, "I don't know if I want to be part of the system that helps you achieve your dream of being in the classroom when the system denied me my dream of graduating."

To have this job I love, and work with students I love and care about, at some level I wonder whether I have to be complicit in this system that's failing the vast majority of students, who never find us. I have the opportunity to meet eighty students a year when the local high school has pushed out many more. I have this awesome job, and I can make authentic personal connections with very intelligent young people who have not been given a chance. But I can only do this because of a system failing so many of them. That's the conversation we need to be having, and it needs to be led by our students.

Can we have an honest conversation? That's what Larry, a young push-out, was able to ask. His honest connection with me caused me to really rethink what I do.

For more information, go to http://www.ted.com/tedx/events/11924 and http://www.youthbuildcharter.org/about-us/